Despite Northwestern’s prestige and price tag, some students still struggle with food insecurity.

There were times last year when SESP fourth-year Alex Macedo would go the whole day without eating.

“All I would want to do was sleep,” he says. “When I didn’t eat, obviously, I would get very depressed … It just became such a bad pattern.”

That pattern, Macedo remembers, grew to be all too present in his life, as he was constantly trapped between barriers like bad timing, high grocery prices and lack of accessible, nutritional meals.

Macedo was food insecure. And on Northwestern’s campus, he’s not alone.

Going hungry

Approximately 48 percent of students at two-year and 41 percent of students at four-year institutions face food insecurity according to a 2019 report from the Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice.

Although these numbers vary from school to school, Northwestern is no exception. While there are no University-collected statistics on the issue, between January and August 2019, more than 330 students used Purple Pantry — the weekly and by-appointment food pantry on campus. The full scope of students struggling on campus remains unknown.

“Certainly Northwestern is aware that the support for first-gen, low-income students needs to be a little bit different [than] the support necessary for students who come from wealthier backgrounds,” says Mary Deeley, pastoral associate at the University’s Sheil Catholic Center and head-coordinator for Purple Pantry. “[But] I honestly think, even now, there is a reluctance to admit that there might be students who are food insecure.”

Data collected at Purple Pantry begins to reveal how food insecurity manifests at Northwestern. Almost 64 percent of students receiving support from the food pantry live off-campus, suggesting that the problem worsens once students no longer live in dorms. Of those living off-campus, lack of money was the largest barrier to getting food; for those living on-campus, class during dining hall hours and snacks for late nights became a financial burden. Most Purple Pantry visitors are female (59 percent), and most are Hispanic or Latinx (40 percent).

Since every situation is unique, Northwestern’s Student Enrichment Services (SES), an office that primarily partners with first-generation, low-income and/or undocumented students, supports those facing food security on an individual basis. Students can contact SES via online interest forms or walk-ins. According to Kourtney Cockrell, SES’ s founding director, the office always tries to meet with students in person so they can fully understand the situation and connect them with resources.

“We’re very much a first-stop shop, not a one-stop shop,” Cockrell says. “We tend to identify gaps and then help fill those gaps and work on policy change.”

Cockrell says the first step in supporting food insecure students is often a referral back to financial aid. Because financial aid is meant to cover personal expenses such as meals, repackaging a student’s aid to account for food insecurity can put essential money back in their hands.

Another referral site is the federal government’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), informally known as “food stamps.” All students who are work-study eligible and work 20 hours per week also qualify for SNAP, and SES offers weekly drop-in SNAP hours for students to learn more about the process of collecting benefits.

SES also connects food-insecure students to on-campus services such as Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS) and Purple Pantry, where an SES AmeriCorps Vista volunteer works weekly. Cockrell says she refers one or two students to the pantry every other week through SES’s online interest form.

SES was also Macedo’s point of entry to Purple Pantry. He started visiting his first year as one of the pantry’s first users.

“When spring break came around, me and a couple friends decided to stay on campus,” he says. “We were worried about food because all the dining halls were closed.”

Situations like Macedo’s inspired Deeley to take action. After reading an article in The Daily Northwestern about students gathering up snacks from the dining halls before breaks, she contacted staff and campus ministry partners about creating the pantry.

“There’s no way students should be going hungry — ever,” she says.

An issue by definition

While at least hundreds of fellow students are in need of nutritional support, Macedo believes that most of the Northwestern community does not understand food insecurity. Macedo himself wasn’t always sure how to recognize it, despite experiencing it long before his time at Northwestern.

“I think there’s a lot of people that suffer from food insecurity, but they think that food insecurity might be either, ‘Oh, you just don’t have access to food,’ or that you simply don’t have the resources,” Macedo says. “[But] it also applies to whether you have actual, nutritional food.”

The Hope Center is an action research team that conducts the #RealCollege survey, the nation’s largest annual assessment of basic needs security among college students. The nonprofit defines food insecurity as “the limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe food, or the ability to acquire such food in a socially acceptable manner. The most extreme form is often accompanied by physiological sensations of hunger.”

Yet food insecurity can have countless faces, which makes it that much harder to recognize or self-identify on campuses like Northwestern’s. Deeley stresses the importance of recognizing that food insecurity can manifest differently within Northwestern’s student body.

“Especially for students on campus, [people think], ‘Well, they get tuition, they get room and board. What food insecurity?’” Deeley says. “But then again: food is also social. Food is also being able to offer your friend a snack.”

Food insecurity can also differ in frequency; some students struggle with access to food on a more episodic basis.

“[For off-campus students who are] budgeting big time, those are students who get a lump sum of money at the beginning of the quarter and have to make it last,” Deeley says. “What happens if their mom’s car breaks down, and the family goes, ‘Honey, can we have some of that money?’ What are you going to do, say, ‘No, mom, this is just for tuition?’ No — you’re giving your mom that money.”

Putting food on the shelves

Purple Pantry is a limited resource. Found in the basement of Sheil, it’s only made up of a refrigerator space, three storage and two pantry shelves. And since Northwestern does not provide any official financial support to the service, Purple Pantry is entirely volunteer-run and donor-supported. Its shelves are only stocked due to aid from alumni funds, the dining halls’ Compass Group food provider and the occasional Evanston resident’s extra bag of groceries.

In her 23 years working at Northwestern, this is the first time Deeley can recall such a resource being available to students. Although Purple Pantry is the only food pantry at Northwestern, other on-campus organizations focus on addressing student food insecurity as well, such as Swipes NU and the Campus Kitchen at Northwestern University (CKNU).

In addition to collecting uneaten food from dining halls and packaging it into free, healthy meals for low-income Evanston residents, CKNU works with Purple Pantry, SES and the administration to prepare free meals for food-insecure students.

Swipes NU is part of Swipe Out Hunger, a national nonprofit initiative founded at the University of California in Los Angeles addressing hunger among college students. Previously called “Points for a Purpose,” Northwestern’s chapter officially re-branded and merged with the national organization in 2017.

In the past, Swipes NU gave students an opportunity to donate dining dollars by swiping their Wildcard at dining hall drives and on-campus C-stores. Swipes then collected the money to serve both food-insecure students and members of the greater Evanston community by funding soup kitchens, aiding Purple Pantry/CKNU and providing educational opportunities for students.

According to Swipes NU’s current president, McCormick third-year Avram Bar-Meir, there hasn’t been a drive in about a year and a half due to the recent transition between Northwestern dining providers. However, Swipes NU plans to have a dining-hall drive at the end of fall quarter.

“We’re very excited,” Bar-Meir says. “Even small donations can go a long way — if every student who is on a meal plan could donate a single dollar, that would be like four thousand dollars, which could end up helping so many people in so many amazing ways.”

Stacey Brown, director of dining at Northwestern, is the adviser of Swipes NU. She says working with organizations like Purple Pantry, Swipes NU and CKNU is essential to both Northwestern and Compass Group’s missions.

“Throughout this year, we are focusing on programming that can help students learn more about the benefits we provide, but also the resources around campus and in the community at large,” Brown says.

Northwestern Dining is currently finishing a food insecurity website that will launch during winter 2020. According to Brown, the website will include information on applying for SNAP benefits, transportation and grocery shopping on a budget.

Brown also says Northwestern Dining offers a new kitchen teaching series focused on how to cook on a budget.

The Multicultural Center and kind professors, especially those in his Latinx studies courses, often supported Macedo. He recalls times in which the food they gave him got him through the day.

“If [a professor] had not bought me that [meal], I probably would not have eaten for another six hours,” Macedo says.

Macedo emphasizes that ethnic studies departments have created a unique culture of caring and support for students in need like him.

“A lot of the minority students on campus feel a type of connection and home to those places, and it obviously makes sense that if they’re feeding you, that is a connection to home,” Macedo says. “It’s just that sense of understanding of where one comes from, and understanding why it’s so hard sometimes for us.”

Reaching out

Despite the support he’s found, Macedo believes there’s still one factor that continues to impede these resources’ effectiveness.

“There are people who are dedicated to giving out free food when there is the chance,” Macedo says. “But then again, you have to know that these things exist, and I don’t think enough people do.”

Cockrell also feels a lack of awareness about the issue and on-campus resources, especially for students who don’t interact with SES.

“I think we need more support around outreach, [but] that’s just something we just don’t have a lot of capacity for,” Cockrell says. “I think what we can do better is making sure it’s not just an SES thing, but that all the schools and units are aware, so that wherever students are connected, they’re getting that information.”

Deeley agrees. On average, 10 to 20 students stop by each Thursday Purple Pantry operates, but she suspects that there are more who need the services.

Deeley’s suspicion is supported by anonymous data from Purple Pantry. According to their visitor intake forms, over 74 percent of Purple Pantry users noted that they would be sharing the food they collected with others, and over 65 percent expressed that they were aware of other students on campus with inadequate food.

Life on empty

Northwestern’s case is a reflection of what is happening across the country; food insecurity is a national concern. The Hope Center found that just 20 percent of food insecure students actually receive aid from SNAP. In addition, campus food pantries often serve as a “crisis response,” which compensates for a lack of more preventative support for food security.

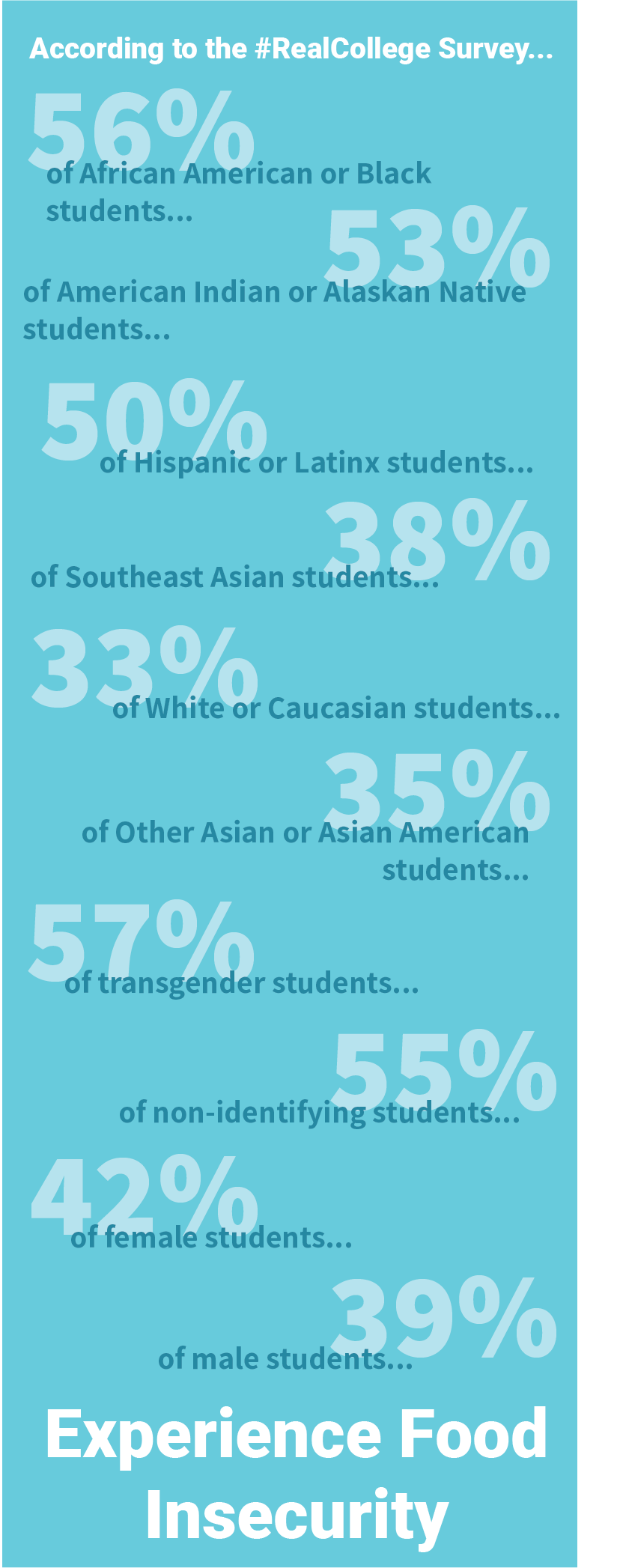

The Hope Center also maintained that food insecurity affects certain groups to different extents. Rates of basic-needs insecurity are higher for students belonging to marginalized communities, including students who belong to racial and ethnic minorities, are transgender and/or low-income.

A 2018 report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that the most common factor for college students’ food insecurity is being low-income. Most of these students were found to also have one additional “risk factor” associated with being food insecure, such as being a single parent or first-generation.

According to the GAO, being food insecure has a large negative impact on academic success, undermining college experience and credential attainment for many students nationwide. Macedo remembers food insecurity affecting both his academic life and mental well-being.

“I would start missing class in the morning, or I would be very sluggish and wouldn’t have the energy to do my homework,” Macedo says. “At some points I would have so much capitulation that I wouldn’t really care if I missed an assignment.”

Outside of the classroom, lack of food access often reflects even greater issues in students’ lives as well.

“[With] any student that reaches out about food insecurity, really any student that reaches out to this [SES] office, I find that the one thing they’re asking about is often tied to a larger issue,” Cockrell says. “If you can’t afford food, you probably might be struggling with lots of other things: rent, personal expenses, all sorts of things.”

The Hope Center found a strong intersection between food insecurity, housing insecurity and homelessness in college students. In the past year, 30 percent of respondents from four-year institutions were both food and housing insecure.

Closing the gaps

Although he believes that Northwestern has been aiming to address the issue, Macedo thinks it’s important to recognize the barriers that persist.

“I feel like Northwestern has the habit of just making something and saying, ‘We fixed the problem and there’s nothing else to do, instead of saying, ‘Okay, this is the first step in solving it,’” Macedo says.

He believes one next step is institutional aid for on-campus services. While Deeley is grateful for donor and volunteer support, she wishes for a permanent Purple Pantry space and a paid employee to coordinate it.

“We’re kind of at capacity here [in Sheil],” Deeley says. “I couldn’t fit in another shelf in if I wanted to.”

Deeley says she’s been lucky to have helpful colleagues and a boss that allows her to dedicate time to the pantry, but is concerned about the program’s longevity.

“What happens if I leave?” she says. “[Or] if I get a new boss who says, ‘Really, we need your time with us?’ What happens to [Purple Pantry] then? That’s why I want to push Northwestern a little bit.”

Macedo advocates for increased funding for SES and programs like QuestBridge. He feels there should be increased support for off-campus students, who often don’t have meal plans. That’s why after living off-campus as a third-year last year, Macedo decided to move back on campus.

He says even slightly smaller adjustments, such as bringing back meal equivalencies that made campus restaurants more accessible for students or providing snacks in dining halls to be easily eaten later, could make a difference. Additionally, he feels that combatting the lack of awareness should start as early as possible.

“A great thing would be to incorporate these kinds of things into Wildcat Welcome, because that is when students are introduced to this campus ... A lot of [Wildcat Welcome] is never tailored to students’ knowledge of things that will be helpful for those who aren’t white or who aren’t rich,” Macedo says.

At the same time, Macedo doesn’t want possible dialogues on the issue to have negative effects on students living with food insecurity.

“[It’s important] to ensure that students who come from those backgrounds or do associate with that aren’t taking on the burden of the labor of explaining it, or feeling ashamed of any negative connotation of it, because they shouldn’t,” Macedo says.

Bar-Meir also feels the community should work on an increased awareness.

“A lot of Northwestern comes from a very affluent community. [Food insecurity is] not something that they’re used to, it’s not something that they’ve ever had to experience,” Bar-Meir says. “[But] I think it’s just very important that students are aware of things that are not necessarily brought up as often as they should be.”

Although she identifies room for improvement in terms of reaching students on campus, Cockrell, notes the privileged position Northwestern is in.

“[Food insecurity is] a humongous issue at our schools just down the road, like state schools and community colleges,” Cockrell says. “I think that we just need to be really mindful of that. The good news is that we do have the resources. Outreach is different than not having the ability to fix the issue.”