In 1824, a crowded Vienna concert hall eagerly awaited the premiere of Beethoven’s “Symphony No. 9.” The audience went nuts after just the first movement. A couple measures into the second movement, they were so excited that they whooped and clapped while the orchestra was playing, and the conductor had to start over. Right up until the conclusion of the finale, they never bothered to restrain their applause—people were out of their seats, screaming, crying and cheering.

In 2019, the sold-out crowd at Pick-Staiger concert hall held its breath as the Northwestern University Symphony Orchestra began to perform Beethoven’s Ninth. For more than an hour, we watched with rapt attention. Coughs and grunts punctuated the otherwise dead silence between movements. I nearly fell asleep in my chair. The only evidence anyone enjoyed the performance was the standing ovation at the end — after an hour of sitting completely still.

This change in etiquette harms audiences, performers and the entire classical music industry. To understand why, it’s important to understand how that change occurred.

While many composers wrote for royalty, classical music was more often intended for the wider public to enjoy. Symphonies inspired and entertained generations of people from all backgrounds. Beethoven’s Ninth, for example, was a highly personal project that reflected fundamental aspects of human nature: anguish, triumph, change. Commoners and connoisseurs alike raved over it for decades.

As popular styles of music shifted, society stuffed Beethoven’s symphonies into elite concert halls where only the old, the rich and the powerful could adore them. Connoisseurs monopolized classical music and made what was intended to be universal exclusive. Performances became quieter, more elegant, more pretentious events. Concert etiquette now reflects the whims of the bourgeoisie.

Beethoven, who wholly despised the Austrian aristocracy, is rolling in his grave.

I’m deeply passionate about classical music. I have more Beethoven merchandise than Northwestern merchandise. What particularly stirs me about symphonies is that they can express full, complex narratives without a single word. In the same movement, an orchestra can present silky melodic passages and energetic, dance-like lines. But I can’t clap between movements without a dozen boomers glaring at me like I just committed a mortal sin. I can’t get up and dance without security escorting me out of the concert hall.

Classical music deserves an audience that engages with every performance. The current audience, however, is full of elites who favor emotionally restrictive etiquette to appear more sophisticated. As a result, the industry — and the genre — appears inaccessible to anyone who isn’t a rich, white boomer.

It’s no secret that the industry suffers from a critical lack of diversity. Larger issues, like female composers’ absence from programs and the lack of minority performers in orchestras, have been investigated time and again to little avail. Many of these problems are rooted in systemic racism and sexism. Current etiquette plays a role in sustaining classical music’s image as exclusive; obedience culture particularly harms minorities and women who already suffer from expectations of obedience.

This cycle must be broken. Abolishing “sophisticated” etiquette won’t suddenly make the genre accessible to all — only major institutional reforms can do that — but it’s a small, easy start. Industry leaders must actively include conductors, composers and performers who aren’t white men, but they also need to see that audiences are willing to break with modern standards. That’s why concerts desperately need to return to their roots — to dancing, clapping, humming along, and enjoying a symphony without shame.

Audience behavior isn’t the only thing suffocating under the restrictions of classical music culture. Performers are also subject to stringent customs of manners and dress. It’s almost unthinkable to picture a conductor in anything but a sharply-tailored suit. For the most part, musicians stick to similar uniforms. Female soloists and conductors tend to face extensive criticism for violations of these codes.

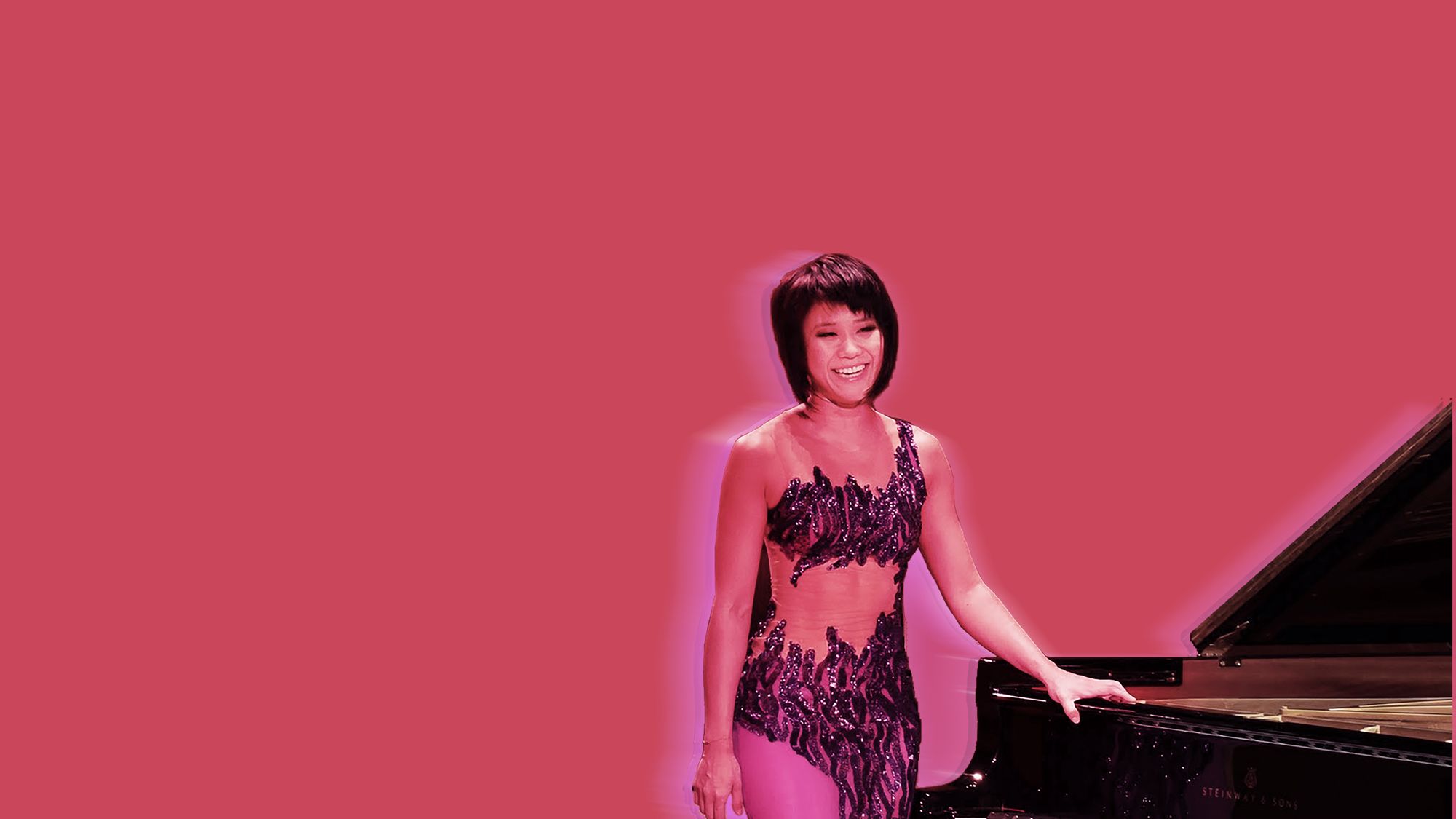

Take Yuja Wang, the Chinese pianist who regularly makes headlines for her outfits: high heels and tight, colorful mini-dresses. Her attire matches her performance style: vibrant, fiery, glittering with personality. And even though she’s won the most prestigious musicianship awards in the industry, critics never seem to tire of calling her “skimpy,” “improper” and “offensive.”

The reality is that there’s no historical or social reason why classical musicians need to wear formal clothes. A uniform doesn’t contribute to a performer’s musicality. If anything, dress codes hinder performances because they don’t allow soloists to fully express their identities. Any attempt to replace formality with personality should be celebrated instead of shunned. Beyond that, Yuja Wang shouldn’t be the only musician to dare enter the realm of self-expression — more soloists and conductors should step up and challenge the norms.

While fashion and applause may seem trivial, these arbitrary standards contribute to classical music’s image. Some people who aren’t fans of classical music believe concerts are boring, fancy events. That’s because they are; only those within the industry can change that.

Luckily, Northwestern has no shortage of young classical music fans. The 400 students in the Bienen School of Music possess sensibilities and talents that my puny Medill mind can barely comprehend. The school’s existence is proof that classical music can appeal to an extremely diverse audience. The revolution can start here.

Clap between movements. Treat famous performers like pop stars. Dance around in your seat if the music moves you. Dress sexy, or metal or punk for your recital. And if any of these suggestions seem too daunting, at least think about why these rules are in place, and why anything should dictate how you enjoy music.

Make Beethoven proud. Make classical music sexy again.

Editor's Note: The views presented in this story belong to the writer are not necessarily reflective of North by Northwestern as a whole.