“The cries in the dark that nobody hears / Here where I stand at the turning of the years,” Jean Valjean laments. At its heart, Les Miserables revolves around people who move unseen. From an ex-convict rising anonymously through society to wounded revolutionaries being dragged through the Parisian sewer system, the musical beckons us to listen to the choices people make when nobody is watching. Composed by Claude-Michel Schönberg with French lyrics by Alain Boublil and translated by Herbert Kretzmer, Les Miserables is one of the best-known musicals of all time, and for good reason.

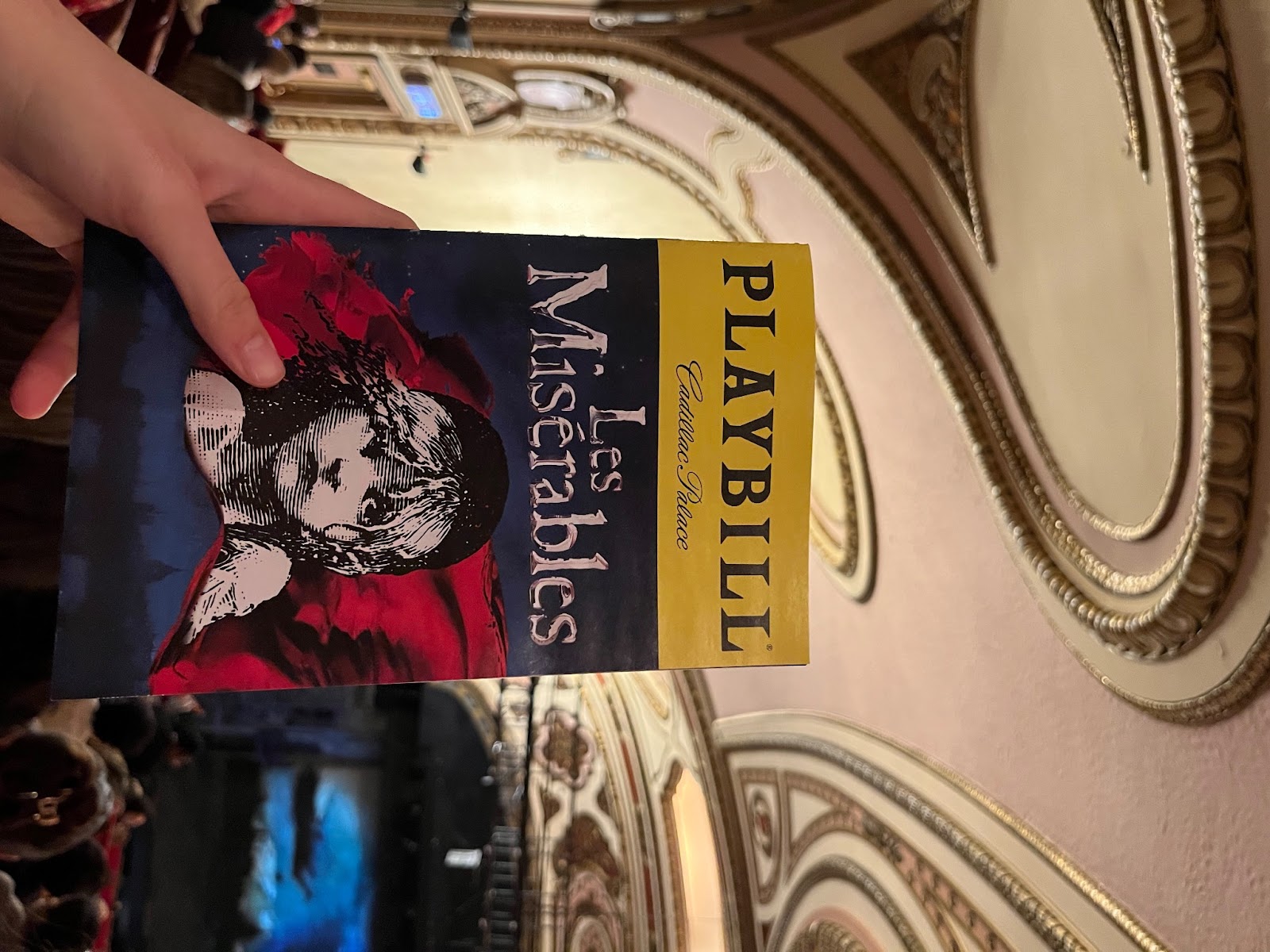

Last weekend, the US National Tour of Les Miserables closed its run of Chicago performances at the Cadillac Palace Theatre. Having grown up with the various cast recordings, trudged my way through Hugo’s prose and rewatched the 2012 movie adaptation countless times, it was surreal to be clutching a playbill in the crowd as the crashing, resonant notes of “Look Down” echoed through the theater.

Watching producer Cameron Mackintosh’s Les Miserables in theaters for the very first time filled in the concrete details I’ve been imagining for years. The theatrical stage emphasizes certain details that punctuate the songs – for example, the fateful silence as Fantine leads a man into a ramshackle building in order to send money to her daughter Cosette’s caretakers. Similarly, the parallel scenes of Javert (Preston Truman Boyd) grabbing Valjean’s (Nick Cartell) hands while the latter is on his knees, still in shackles, to unknowingly shaking his hand as equals is another of the many impeccable elements.

Valjean and Javert are not the only characters whose paths cross again. Eponine, played by Christine Heesun Hwang on the tour, resigns herself to helping her unrequited love Marius woo Cosette; the same girl that Valjean rescued from Eponine’s parents, the Thenardiers, years ago. Romantic love, however, takes a backseat in this lauded musical. A much stronger message pervades each character, each soaring aria – as Eponine, Fantine, and Valjean sing in the final song, “to love another person is to see the face of God.” When Valjean kneels in front of a young Cosette and the students gently carry Gavroche’s body away, it becomes clear that even in the face of conflict and fear, these actions mean everything.

Of course, love is not always possible. Instead, one can hope to be as “rich as Croesus,” like the Thenardiers dream. The innkeeper couple, played by Matt Crowle and Christina Rose Hall on the tour, were classic crowd favorites. Their jaunty “Master of the House” number garnered one of the longest applauses of the entire show. With lines like, “But lock up your valises / Jesus! Won't I skin you to the bone!” and “Everybody loves a landlord / Everybody's bosom friend,” comical laments bring the bawdiness of the lowlife characters to life. They are part of what makes Les Miserables so appealing, as the musical captures both gleeful mania as well as existential grief, all encapsulated in its nearly three hour run-time.

The visual staging of the musical reminds one of the possibilities of theater, in an age where so much is relegated to the big screen. The mise-en-scene during Fantine’s death was particularly striking. Fantine’s deathbed is illuminated in white, the light spilling onto Valjean’s shoulders as he comforts her in her last moments. Meanwhile, Javert emerges from the other side of the stage, a doorway next to him shrouded in a darker, yellow light. Even as Fantine fades from life, Javert rises from the shadows, ready to confront Valjean once again in a visually striking contrast. In many ways, Fantine and Javert are just as much a polar pair as Valjean and Javert, and to some extent, I find them more compelling. Javert is very much a static character, to the point where his ultimate demise occurs because he cannot come to terms with Valjean’s evolution, from chain gang prisoner to a prosperous mayor. This idea is foreshadowed when Javert sings, “Men like me can never change / Men like you can never change.”

To be honest, before watching Les Miserables live, I never really understood why people hated Russell Crowe’s Javert in the 2012 movie adaptation. But after listening to Boyd’s performance, I can confidently say that Crowe’s voice does not do Inspector Javert justice. The raw desperation as Javert spirals, culminating in his leap off a bridge, was incredible – especially as a combination of choreography and special effects perfectly simulated free fall into the Seine’s murky depths.

Using light to depict deaths – especially on the barricade – was a fantastic stylistic choice. This allowed each member of Les Amis de l’ABC, the student revolutionary group, to have their moment, quite literally, in the spotlight as they died for their ideals. Most notably, their leader Enjolras, played by Northwestern alum Devin Archer (SOC ‘10), rallies the group one last time, even in death as his body is laid out next to that of the street urchin Gavroche. Slowly, they are carted away, leaving the audience with the haunting knowledge that in this struggle, there is no mercy even for the blazing young figures.

I’ve always considered Les Amis to be one of the most compelling ensembles in media, with their fervent passion for change, naive idealism, and of course, resolute final stand at the barricade. Their rousing rendition of “Do You Hear the People Sing?” only adds to the appeal. But the message Les Amis represents is more resonant than ever. Especially now, as student voices around the world find themselves at the forefront of political activism, it’s difficult not to want to leap out onto the stage and join the barricade too.

Thumbnail image by Yong-Yu Huang.