“Abolition is big on imagination,” Medill second-year Jaccquy Germain says.

As a writer and senior editor for BlackBoard Magazine, Germain joins a movement of artists and creators on campus and nationwide who are bridging the connection between artistic imagination and abolitionist imagination. She feels most people see revolution as blood-stained and brutal, reinforced from history: the hills of New England, the streets of France, the fields of Haiti. In 2014, after scenes of demonstrations and violent crackdowns in Ferguson, Missouri, a Roper Center poll found that 59% of respondents thought the Black Lives Matter protests had “gone too far.”

But as the Black Lives Matter movement relaunched into prominent news spheres this year in response to the lynchings of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, an adjacent revolution — less evident in the dramatics of cable news — has emerged to the forefront.

People across the country have wrestled with what change looks like. Muralists and graffiti artists responded by decorating petitions such as “A WORLD WITHOUT POLICE” onto streets and buildings in dozens of major cities. Musicians have released songs centered around justice and injustice such as Noname’s “Song 33.” Beyoncé’s film “Black Is King” gained attention for parading the beauties of Blackness. Past works of Black creators also were elevated to the spotlight in response to the events of 2020. Ava Duvernay’s 2016 documentary“13th” served as a resource to people seeking to understand the basic injustices of the prison system. The writing of revolutionaries from George Jackson to Angela Davis helped people dive into exploring abolitionism. Students on Northwestern’s campus are playing their own roles in driving artistic revolution.

Weinberg fourth-year and art history major Brianna Heath gives an explanation for the ongoing interaction between change and creativity: “Revolution requires imagination, while at the same time, artistic practice is imagination manifested.”

Heath has worked as a curatorial intern at Northwestern's Block Museum of Art and the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, and she is currently completing a curatorial internship at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. Through her time focusing on Black contemporary visual art, she has found that artists deploy countless ways — some very subtle — to reimagine. Artists rethink patriarchy. They rework “love.” They redefine “abolition.”

“I think the people who are painting because they want to bring a sense of peace to themselves and the community that they are painting for. That’s revolutionary because it’s art for care,” Heath says. “Care is a revolutionary act.”

From the walls of the museums where she’s worked to the art history classrooms at Northwestern, Heath has noticed the value placed on “fine art” or what Heath calls “capital ‘A’ Art.” She says white people have always been the definition of “capital ‘A’ Art.”

“No one has ever been in opposition to a white person making art, she says.”

When the creative ideals of European men are maintained as the default, others are condemned for not replicating them. This places Black artists outside the bounds of “Art.”

She says that for Black people in the mid-20th century, the title of “artist” was equated with “revolutionary” because Black artists did not have access to mainstream platforms. Black artists thus created for themselves and their communities.

“Art that is for the self is revolutionary because even your existence is a revolutionary act; we should not be here,” she says.

Heath adds that even as Black artists increasingly gain access to more mainstream platforms, their work is not the model; Eurocentric art remains occupant. She says Black art usually serves other purposes than just beauty; it was made for the self or for the community or for political gains. For this reason, Heath believes “all Black art is — in some sense — revolutionary.”

In June, Communication second-year Marcela Okeke joined a gathering of protestors occupying a Chicago intersection in honor of the late 19-year-old activist Oluwatoyin “Toyin” Salau. Okeke says there were much less people present than she expected to see.

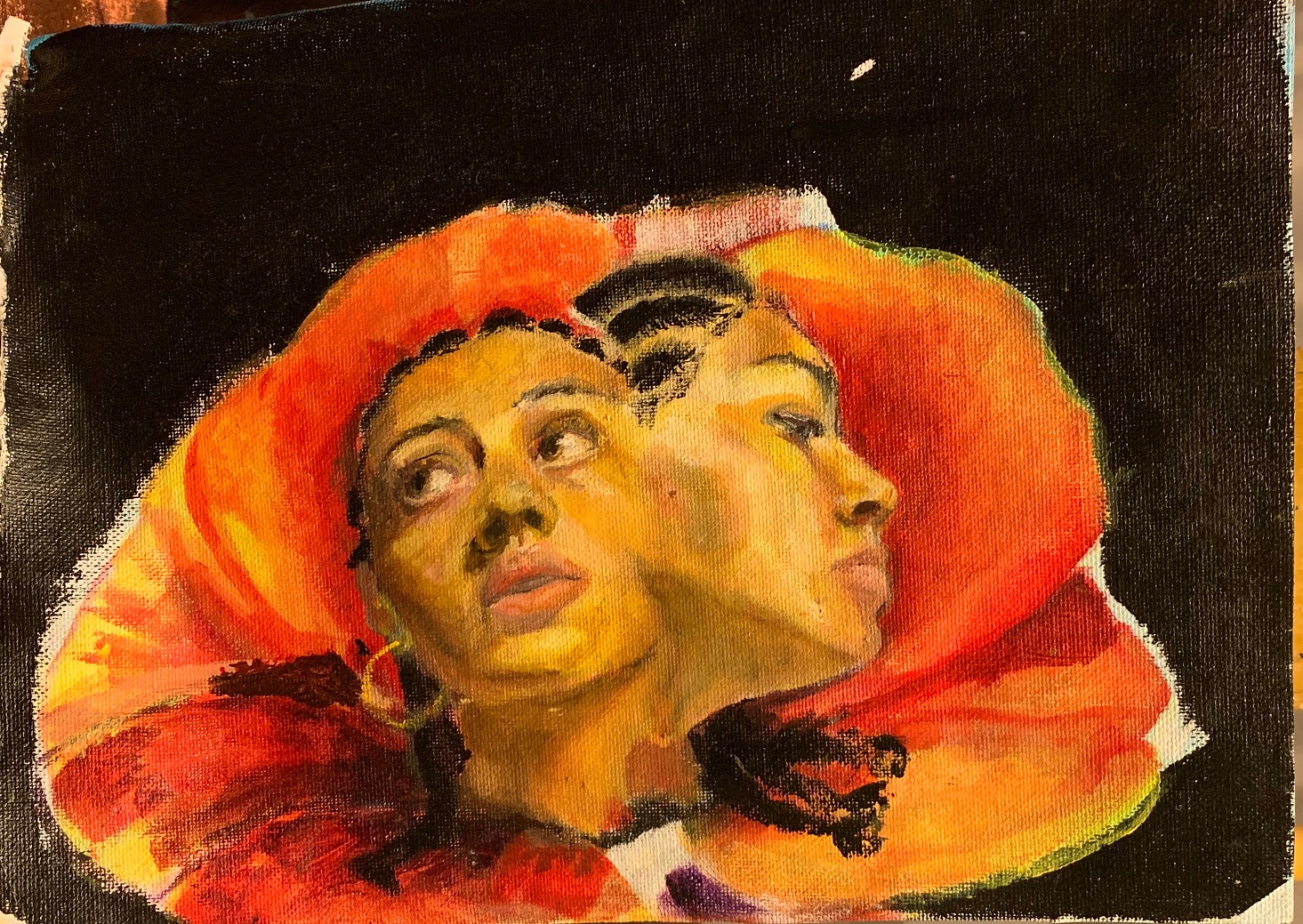

Okeke says even though the Black Lives Matter movement is led by Black women like Salau, it often overlooks them. Salau boldly stood up to detest the murder of Black men, but her alleged killer who confessed to the murder is a Black man. Her death, along with disappointment in the public’s lack of response, inspired Okeke to explore her own Black femininity. She sought to rebel against the placement of Black women as outsiders or other than. Okeke carried a motif of interconnection between Black women and nature across many of her recent paintings.

The paintings depict aspects of nature as being one with Okeke’s portraiture: a branch bound to a canvas adjacent to her arms; flowers pasted in her hair.

“We’ve been here as long as the Earth’s been here; it’s so natural to be Black and woman,” she says.

Medill fourth-year Rory Tsapayi, who is also an art history major, draws an alternative to “fine art” as “an art of the people,” which he describes as uniquely precious because it is crafted to uplift oppressed groups. It is catered to a certain audience: not museum frequenters and academic elites, but rather for the people suffering under systems of oppression. It is created with accessibility — rather than critical recognition — in mind.

Much of Tsapayi’s studies have focused on late-twentieth century South Africa, where photographers fueled the anti-Apartheid movement. Staffrider, a literary and arts magazine, played an intensive role in shaping anti-Apartheid photography. Tsapayi is bringing Staffrider’s archives to life on social media, posting photos from each volume on an Instagram account he created: @staffriding.

“A photo is just as subjective as a painting or a piece of music because the photographer is making a lot of choices,” Tsapayi says.

The Struggle Photography movement kicked off in the early 1980s among photographers who wanted to elevate photography’s role in “the struggle” against Apartheid. The duty of Struggle Photographers was clear-cut, according to one 1982 article from Staffrider: juxtapose the horrors and injustices of Apartheid with messages of hope and resilience.

Balancing these two seemingly dichotomous themes required photographers to make precise artistic choices according to the 1982 issue of Staffrider offered photographers suggestions including “complete utilization of natural un-contrived light” and “the operator’s correct and crucial definition of his picture’s border.” Struggle Photography also featured human subjects. Many of the photos displayed difficult labor, such as a 1981 photo by Lesley Lawson that centers a Black steam-iron operator in a textile factory. The area around the subject’s hands is motion-blurred because of the quick movement of the machine.

“Even though [photography] is not objective, it is very true to life; it’s very easy to read,” he says.

A report from Columbia University's Case Consortium@Columbia explains that educational disparities between Black and white citizens left the former with far less access to the world of fine art. Education for Black South Africans was funded by taxes they paid, leaving Black schools with far less money than white schools. The report shows that in 1961, only 10% of Black teachers in South Africa even had a high school education of their own; classrooms were packed with an average of one teacher for 58 students.

These educational conditions did not come close to providing Black students the tools to critically analyze paintings or dissect poetry. So, photography served as a powerful medium for connecting Black South Africans. Because the art form directly replicates real life, audiences are meant to more directly resonate with it. The photographers understood that their medium was accessible by the masses.

Tsapayi says the photos gained traction for the movement in South Africa and captured the attention of people all around the world as the horrors of Apartheid became better known on the international stage.

Almost four decades later and over 4,000 miles away, the student-led Northwestern University Community Not Cops (NUCNC), which calls for Northwestern administration to disarm, defund and disband police on campus, is echoing Struggle Photographers’ political subversion through digital multimedia collages. The group creates graphics that juxtapose images of officers heavily guarding buildings around campus with videos of student protestors burning banners, audio of protestors chanting or images of signs that declare their demand: #CopsOutOfNU. NUCNC’s thousands of followers have interacted with the graphics across social media hundreds of times, spreading the group’s message across the internet.

Tsapayi points out that there are active and intentional decisions that go into protest art: NUCNC social media managers must decide which images to include, where to place each element and what audio to overlay. He says this art is a part of a larger movement of art emerging from the current Black Lives Matter movement. On Instagram, portraits of Breonna Taylor and others murdered by police wearing flower crowns have gone viral. But Tsapayi says even mediums as simple as cardboard protest signs can employ these powerful artistic choices.

“I think there is something to be said about someone just taking a thick Sharpie to the back of an Amazon box. That’s not a neutral action,” he says, paralleling the decision-making involved in making a protest sign with the decision-making of protest photography.

In South Africa, as Struggle Photographers’ work gained popularity, some artists chose to capture photos in ways that made less explicitly-political statements in their work. White photographer David Goldblatt’s work is a role model of this. Some of his photographs capture social interactions: A farmer's son with his nursemaid; the farmer’s son is white, the nursemaid Black. Other works center the interactions of people with landscape and architecture: Spec housing and children on the veld at Parkrand shows white children playfully bounding atop a mound of dirt. Adjacent to them is a neighborhood under construction. The photo shows land being actively occupied to build a paradise for white people. Some of Goldblatt’s most subtle photography is desolate landscape photos of land or buildings. A pair of photos from 1977 and 1986 capture the same Republic Islamic Butchery. In the second photo, half of the building has been destroyed. The area has been declared “whites only.” The owner is Black. Neither image features human subjects as a Struggle Photography would, but in accompaniment with each other, they tell a dark story of colonization.

Santu Mofokeng’s photography, like Goldblatt’s, diverged from the Struggle Photography style. Mofokeng encapsulated mysticism, spirituality and ambiguity. He manipulates shutter speed in works such as “Church of God, Motouleng Cave, Clarens,” portraying the subject of the shot in blurry motion against the background of the static cave. The location of the photo is a religious site important to followers of indigenous faiths. Under white occupation, many people began practicing Christianity or combined elements of the two faiths. In a way the faiths, like the photo’s subject, are in blurry transition while the cave remains static.

Goldblatt’s and Mofokeng’s holding their cameras elevates them to the position of storytellers. They chose to capture scenes that didn’t seem political — construction zones, butcheries, and caves — but they were subtly capturing effects of colonialism: land being taken to build a suburban playground; indigenous religion and Christianity melding.

Whether she is utilizing a pen or a camera, Communication third-year Lauren Washington sees herself primarily as a storyteller. She has directed several portrait shoots for musicians including for Chicago rapper Brittney Carter. Washington’s work can be seen on the covers of Carter’s single “Cold as Us” and her debut album “As I Am.”

“Storytelling is so important in how we’ve heard about past revolutions and movements,” she says.

Much like Goldblatt and Mofokeng, Washington does not always focus on obviously political themes. She points to the inherent value of photographing those who share her identity as a Black woman.

“So many times we’re not given the opportunity to shape our own stories or photograph ourselves,” she says.

Taking back control, Washington says, allows Black women to choose what stories they tell. She has noticed that so many of the Black stories that have been told only center pain and trauma that it seems like a requirement. Washington seeks to break the expectation of solely highlighting suffering.

“My work is revolutionary just because as a Black woman, I try to uplift.” she says.

Heath commends this focus on hope in Black art.

“It’s revolutionary to suggest that there can be something different than what we’re experiencing,” Heath says.

But Heath believes many artists and viewers do not envision a world for Black people outside of trauma often enough.

“So many people are fearful of having to imagine,” she says.

So when art invites the audience to interaction with their imagination, its influence is made vivid.

A billboard in Kansas City, Missouri demonstrates this invitation. In white sans serif capital letters, it reads, “THERE ARE BLACK PEOPLE IN THE FUTURE.” The letters lie against a black background. The billboard stands in front of the city’s skyline. The simple text calls drivers and passers-by to envision a world past the one they are immersed in. Then viewers are left with their imagination.

Fourth-year Janelle Yanez aims to bring people into interaction with their own mental creativity through graphic designs.

“I feel like I’m pushing people to think outside the box and think differently and view differently and look at the things you see everyday, but look at them differently,” they say.

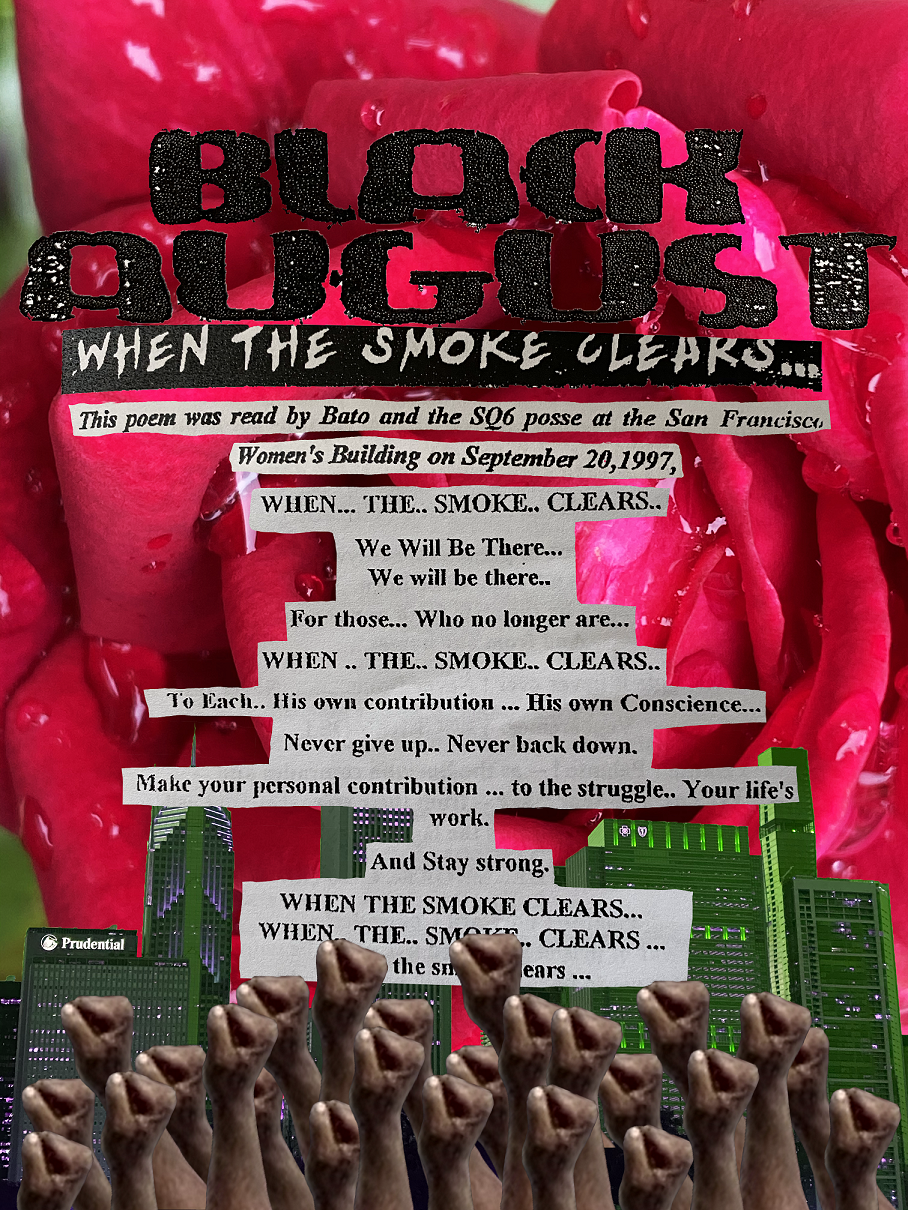

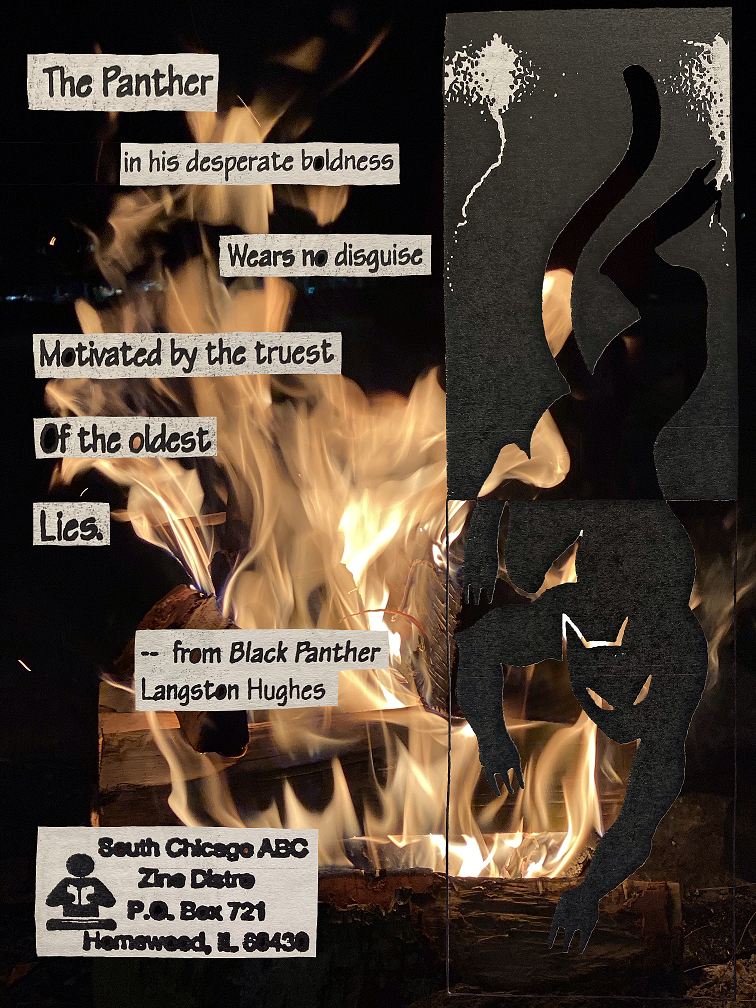

Some of Yanez’s art focuses on the demonstrations and political interactions of revolution. Black August is an example of this. It depicts a crowd of fists raised against a backdrop of the city skyline. Still, the piece points the audience to focus into the future, quoting “When the Smoke Clears,” a poem originating from a 1997 march in San Francisco.

Yanez also incorporates nature, a common theme in their work; the entire edit is pasted above a close-up image of a flower. The motif of nature is a “silly personal thing.”

Yanez’s other works present recurrent themes of self-expression: of body and of defying the norms of femininity. Some pieces include written messages encouraging self-love and expression. Combining and manipulating images in Photoshop gives Yanez the power to bring any image into their edits and have control over elements such as size. They can include images taken at different times and places and even access elements from the internet’s endless array of sources in a single design. Yanez says people have been sharing similar messages for years, yet the creative graphics allow Yanez to express them in new ways. They share much of their work with other Northwestern students on Instagram. The messages of hope and resilience in the works are meant to be a light to students amidst the struggle for abolition.

A sound-bite from African American poet, musician and author Gil Scott-Heron has made its rounds on social media and has even landed in primetime cable news segments this year:

“The revolution will not be televised.”

On Northwestern’s campus, these creatives are confirming his theory, from challenging traditional artistic norms to developing their own modes of subversion. But Scott-Heron’s explanation of the lyrics in a 1989 interview is less well-known. It taps into the true potential of these students’ work, and the protest art that is echoing across the United States.

“The first change that takes place is in your mind.”