Uncovering pieces in the museum's permanent collection.

Glass walls make the Mary and Leigh Block Museum feel open, and inside, white cabinets house the museum’s permanent collection of over 6,000 works of art. Each quarter, two exhibitions go on display that feature works from the permanent collection and other museums. Many of the Block’s pieces travel around the world to other themed exhibitions. The Block’s collection is smaller than most, but it’s full of rare photographs, sketches, paintings and more. Corinne Granof, the Block’s academic curator, says it’s a novelty to see these pieces in person.

“We’re so used to working with reproductions and seeing things digitally,” Granof says. “It’s a completely different experience to actually look at a print in person and see the ink on the paper and understand how it was made.” The Block Museum, which is approaching its 40th year, features pieces that are meant to create dialogues across academic disciplines, according to Assistant Curator of Collections Essi Rönkkö. As Rönkkö explains, how a museum curates its art dictates the values of the institution it’s associated with and vice versa.

The Block traditionally featured mostly Western art, but recently, its curators are making efforts to highlight global artists and showcase issues the Northwestern community deems important. This includes implementing a “global contemporary strategy” that mirrors the University’s efforts to expand its representation of diverse cultures in campus conversations.

Last year, the Block hosted “Caravans of Gold, Fragments in Time: Art, Culture, and Exchange across Medieval Saharan Africa,” an exhibition with over 250 pieces medieval African history.

Since September, the Block has displayed exhibitions on Latin American, Iranian, Turkish, Indian and Arab modernisms and abstractions. It’s currently hosting “Modernisms: Iranian, Turkish, and Indian Highlights from New York University’s Abby Weed Grey Collection” and preparing to open “Taking Shape: Abstraction from the Arab World, 1950s-1980s” at the end of April.

The Block is free to the public and provides group tours. But it’s also an academic resource. This past fall, the museum supervised 20 class visits and set aside pieces for 306 individual student and faculty researchers. While its temporary exhibitions may appeal to specific areas of study, the museum’s permanent, behind-the-scenes collection contains pieces that resonate with Northwestern students in Bienen and McCormick alike. Here is a selection of the museum’s many hidden gems:

“Miles Davis” by Jeff Donaldson

This portrait of the 20th-century trumpeter is filled with the kind color and expression that Davis contributed to the music industry. Donaldson influenced the Black Art Movement, and he showcases the “Picasso of Jazz” in this hybrid piece the Block Museum acquired in 2017. The sketch was part of the 1960s Wall of Respect on Chicago’s South Side, which featured Davis among artwork depicting other prominent African American leaders.

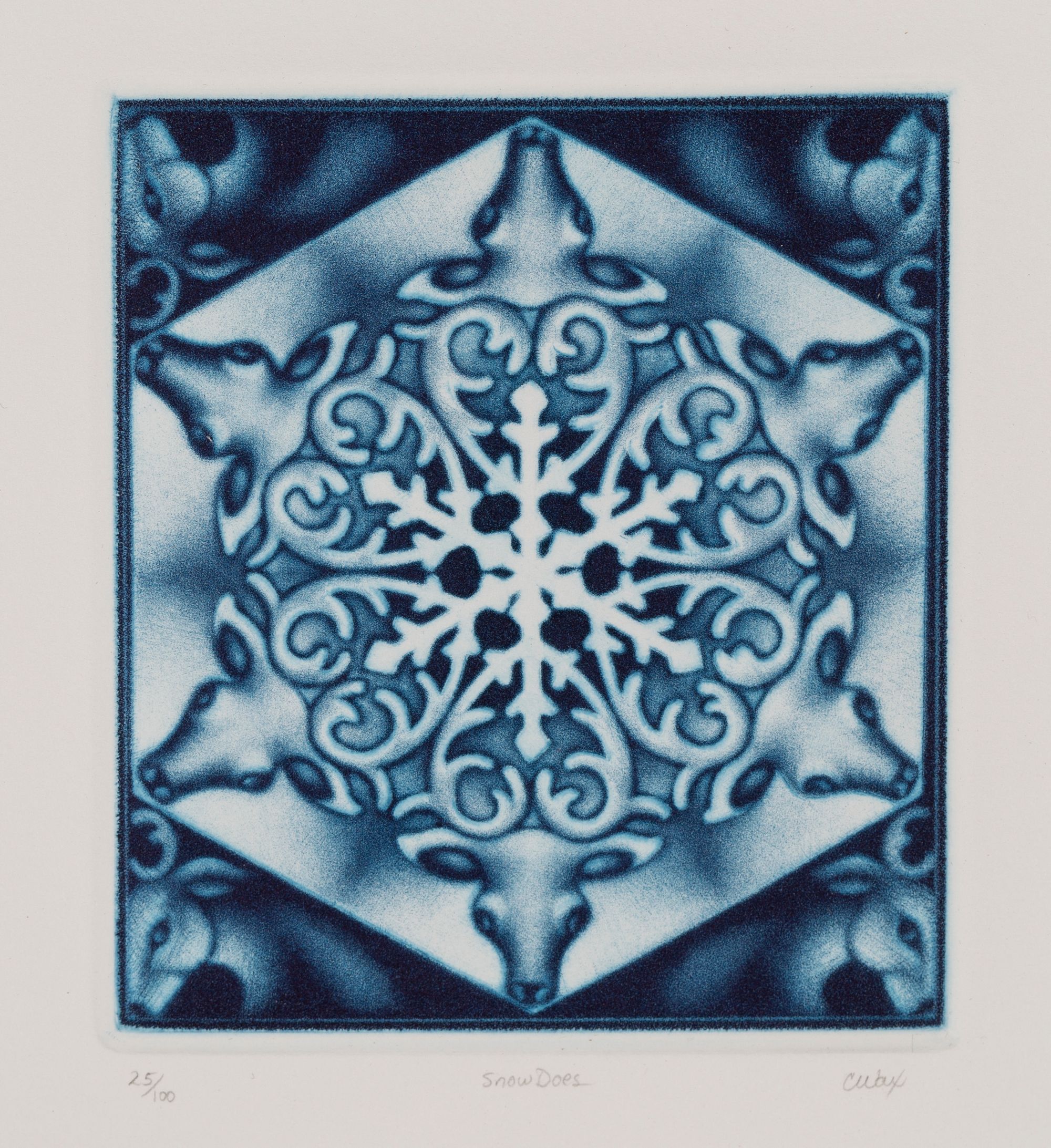

“Snow Does” by Carol Wax

To the average museumgoer, this piece is a mesmerizing snowflake fashioned from winding doe antlers. However, the design engineer or mathematics major may appreciate the intricate mezzotint printmaking process that Wax used or the patterns and symmetry developed in the print. The rare, laborious artform involves making dents in a metal plate at designated depths to control the levels of darkness. The process, which dates back to the 1700s, is seldom used nowadays. Before she fell in love with printmaking, Wax trained as a classical flautist. Her art embodies the magic in seemingly ordinary things like antlers.

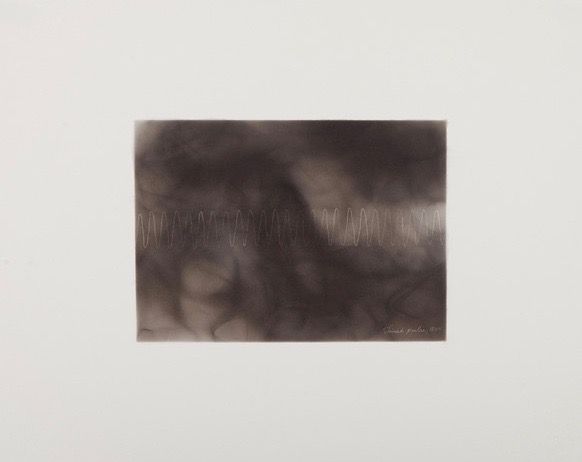

“First Pulse, 1854” and “Flatline (dying of stomach cancer), 1870” by Dario Robleto

Three years ago, Dario Robleto led a talk in conjunction with the Block and the McCormick School of Engineering. His photolithographs of the first recorded heartbeat and flatline are significant in the history of sound, biology and technology. Robleto discovered a series of tracings recorded by German and French physiologists from 1854 to 1913. He captured the first remnants of this pulse with candle soot and hair on pieces of paper. Because little was known at the time about cardiobiology, the physiologists also recorded the heart under circumstances that we now know are unrelated to pulse, like “smelling lavender” and “sadness from listening to a sung melody.” Robleto’s series is groundbreaking in understanding the history of human interest in the heart and scientific advancement.