In a 1996 essay, seminal queer theorist José Esteban Muñoz wrote: “Queerness is often transmitted covertly.” In the ‘70s, gay men used colored bandanas in their back pockets to represent a particular sexual position or fetish. Today, lesbian haircuts and bisexual bobs fill the streets. Historically, queer lives have been lived in secrecy and innuedos, with maybe a glance or touch here and there. Queer and trans folx have developed signals out of necessity; just as physical spaces had to be created for the community to gather, aesthetic choices in hair, fashion and jewelry served as subtler acknowledgements of one another.

But what makes a certain hairstyle queer? What is it about bleached hair or undercuts that can scream “gay”?

Perhaps it’s the word queer itself. Queer ways of being have always subverted the norm. If normal is black or brown or blonde hair, then on a rudimentary level, queer is blue or green or pink.

While these are more easily recognizable choices in certain contexts, queerness by nature takes on fluid forms. As Northwestern students’ stories illustrate, the pull and push between queer choices and hair choices is one of creative tension— both exploratory and productive.

_________________________

After graduating from a conservative high school with written rules restricting students’ hairstyles, Rory Tsapayi was finally able to grow out his hair and add little twist-downs. But it wasn’t until winter quarter of his first year that he decided to take the plunge: joining legions of gay men with bleached-blond hair. Tsapayi originally set out to dye a patch of his hair blond and put it into cornrows. A few glasses of wine later, he decided to bleach it all. (WC: 81)

Winter quarter of first year of high school, Rory Tsapayi decided to take the plunge and join legions of gay men with bleached-blonde hair. He originally set out to dye a patch of his hair blond and put it into cornrows. A few glasses of wine later, he decided to bleach it all. (WC: 53)

“I really loved it at the time,” Tsapayi says. “I feel like that one was more along the lines of, when the gays get a little manic and depressed, they bleach their hair. In reflection, I hate looking at photos of that time.”

Still, Tsapayi decided to give the bleach-blond boy experience another shot this fall quarter. He cut his hair short and got a bleached fade.

“I felt really good about it. When it started growing out, it had this early 2000s frosted tips vibe going on,” he says. “That felt like a growth moment for me.”

For Tsapayi, aesthetic choices were also a way to reckon with his sexuality. He echoed the notion of “compulsory heterosexuality” Adrienne Rich theorized in 1980, where heterosexuality is assumed and adopted regardless of any other desires.

“I think I was just mixing up my look quite a lot at that time,” Tsapayi says. “Which is probably tied to me realising aspects of my identity or feeling very comfortable to lean into different aspects of my identity.”

But changing his hair wasn’t as simple as walking down to CVS with half of his hair covered in bleach. To find a barber who would cater to his Black hair – which often requires products that aren’t available in areas without a sizable Black population – Tsapayi had to walk 25 minutes to Dodge Avenue. He always leaves the bleach in longer than necessary to avoid having it come out “a weird shade of beige.” These extra considerations may play a roll in the perception of queer aesthetics.

“I would say that if I ever see a Black guy with bleach-blond hair, I'm 99 percent sure that he's gay. Versus if I saw a white man with bleach-blond hair, I’d probably assume, but I would have less certainty,” adds Tsapayi.

Still, queer signals are by no means universal. Tsapayi finds it hard to think about of his hair in queer context when he is home in Zimbabwe, since the country’s climate is rather homophobic. There, the historic covertness of queer signaling becomes more apparent to him.

“I don't even know if say, I had peach hair, people would even read that as gay,” Tsapayi says

from doing it the first time in a very manic way to the second where I'm very considered.”

“That felt like a growth moment for me, from doing it the first time in a very manic way to the second where I'm very considered.”

But changing his hair wasn't as simple as walking down to CVS with half of his hair covered in bleach like the first ill-fated time. Despite the fact that there are several barbers near Northwestern’s campus, Tsapayi would have to walk 25 minutes to Dodge Avenue to find a hairdresser who could work with his hair.

“Where can my hair be catered to? There's a lot of spaces it can’t. For Black people, I think there needs to be more consideration,” says Tsapayi.

This consideration doesn’t stop at physical spaces. Black hair often requires products that aren’t always in stock in areas without a sizable Black population; even then, the instructions on the box may not apply in every case. Tsapayi always leaves the bleach in his hair for longer than necessary because he knows his dark hair will otherwise come out a “weird shade of beige.” These individual differences can also permeate societal perceptions of queer aesthetics.

“I would say that if I ever see a Black guy with bleach-blond hair, I'm 99 percent sure that he's gay. Versus if I saw a white man with bleach-blond hair, I’d probably assume, but I would have less certainty,” adds Tsapayi.

Queer signals have never been a universal experience, and this can carry many different implications for people.

Tsapayi finds it hard to think about of his hair in queer context when he is home in Zimbabwe, since the country’s climate is rather homophobic. There, the historic covertness of queer signaling becomes more apparent to him.

“I don't even know if say, I had peach hair, people would even read that as gay,” Tsapayi says.

_________________________

Molly Glick* stood in front of the mirror with a small pair of scissors meant for her eyebrows. She thought to herself, “This is extremely low-stakes. What would happen if I just cut off this piece of hair?”

The rush felt so good that she kept going for an hour.

Trading in her DevaCurl haircuts for a quick DIY bathroom fix was more rewarding than expected. Glick’s brown ringlets rest just below her shoulders now, a drastic change from the long hair she had in high school, where she says she tried desperately to blend in. Now, she prefers a little bit of androgyny.

“Sometimes getting a haircut is kind of manifesting your ideal version of yourself. You're seeing it out in the world. And I definitely do think that seeing my hair dramatically shorter did confirm inner feelings,” Glick says. “I think I had already confirmed my [sexual] identity before then, but it helped me take a step forward.”

_________________________

Ever since she was four, Sophia Simon’s mom would drag her to the salon every two weeks to turn her kinky curls into straight, “nice hair.”

For Simon’s family, “nice hair” was tied to femininity; the pressure to look a certain way brought years of heat damage and resentment. By the time she started high school, Simon’s hair was breaking all the time. It wasn’t until Simon began to untangle herself from those expectations that she stopped worrying about what she did with her hair and how it was perceived. She finally decided to take control, growing out her natural hair into an afro throughout the rest of high school.

“Having more agency over [growing my hair] made me feel like I had agency in other parts of my life,” says Simon.

By December 2018, Simon had cut her hair into a shorter afro, yet she still felt she had too much hair. By January, she shaved her head and started to dye her hair. She’s been bleached-blonde, bright red, purple and even rose gold. Simon emphasizes the red was a clear favorite.

“It was the brightest my hair has ever been. It was like a fire red! It felt fitting to my personality. And I feel like it made me kind of stand out in a way, whereas before, I think my hair was just always so boring,” Simon says.

Simon’s newfound love of experimenting with hair is about more than just standing out. It’s about rejecting people’s perceptions of herself, from her mother’s thoughts on femininity to others’ on her sexuality. Rather contradictorily, as Simon has grown more comfortable with her sexuality, her hair has become both more and less important to her.

“I’ve started caring less about my physical appearance and how it’s perceived by other people. I think my hair has also been a way for me to define myself,” Simon explains. “I think the development of my sexuality also paralleled me shaving and dyeing [my hair].”

While she doesn’t think that hair is necessarily representative of homosexuality, Simon does believe it’s one of many physical ways of expressing sexuality.

“I think that my hair has been a statement of my uniqueness in a way. And I think queerness is uniqueness,” Simon says.

Seeing her hair as a true expression of herself, rather than a way to conform to expectations of traditional views on Black aesthetics, has given Simon the power to accept her hair as-is.

“Just realizing that at whatever stage, my hair is beautiful— whether it's a full afro, whether it's like a little baby afro, whether I have no hair at all— it’s made me appreciate what my hair looks like in all of its stages,” she says.

_________________________

Shanida Younvanich loves her Nintendo Switch. So, one day she took two medium-length sections of her black hair and dyed one a light blue tinged with silver and the other a pale green to match the colors of her game controllers.

“In an ideal world, I would have liked to bleach my whole head and dye it pink. I think it expresses me pretty well,” says Younvanich.

Though she struggles to explain why exactly pink is the color for her, it brings out how she feels inside. For Younavich, it is a way of dealing with an internal reckoning.

Younvanich is a hard-core “Animal Crossing: New Horizons” fan. But for her, it’s more than a good way to kill a few hours a day. Unlike older game versions, in “New Horizons” avatars have no enforced female-specific hairstyle or clothing.

As she’s been questioning her own gender identity, Younvanich has found her Animal Crossing character to be a way to explore these questions.

“You can present as any way you want to, which I think is really nice,” Younvanich says. “I guess it’s kind of symbolic.”

Younvanich also explains that these coded signals depend on context. In her classes, it serves as a talking point that avoids the awkwardness of flat-out asking about someone’s sexuality. When it comes to her family, though, her dual-toned hair isn’t recognized as a symbol of queerness.

“They're a traditional Asian family. They're not going to see my hair like that — like, ‘Oh, she did that because she's gay and she loves Animal Crossing,’” she says.

_________________________

Jess Collins can’t remember whether the street festival she attended the summer after her second year at Northwestern was in Wicker Park or West Logan. She does, however, remember the barber advertising free haircuts. Drunk and in need of a trim, Collins didn’t exactly give them any clear instructions. And so she walked out with a pixie cut reminiscent of soccer star (and gay icon) Megan Rapinoe.

Like many other queer people, Collins’ hair became a statement. This one was much more revelatory than she first expected.

“My first girlfriend thought I was queer because of my haircut. And I had no concept of that myself,” Collins says. “And so I think it almost told other people something I hadn't realised myself, which was quite funny.”

She returned to the same barbershop later because their website advertised a cheap deal on a color and trim job. It wasn't until after she asked her barber if he was going to color her hair that he informed her that the deal was only for beards.

Collins, who has since graduated and moved to London, tends to go to men’s barbers because it makes more sense for her short crop. But this experience isn’t always the most straightforward. Her new 70-year-old Greek barber gives her a very typical “bro haircut”: closely shaved sides and long on top.

Despite this, she’s sometimes charged a more expensive women’s haircut price for the same style that most other men receive.

“It’s interesting to me. I wish there was a barber for women or non-binary people,” Collins says.

With much more free time during quarantine, Chelly Compendio decided to finally bleach her locks.

“There’s that whole joke that girls dye their hair after a breakup. But I dye my hair when my internship has been cancelled,” says Compendio.

45 minutes of application. 45 minutes of waiting. Rinse, condition and repeat three times. A big part of Compendio’s inspiration came from the stereotype of ABG— or Asian Baby Girl— culture. Growing up, her family would tell her not to dye her hair blonde; to them her skin was too dark.

But after seeing a lot of other Asian American girls (specifically other Filipino-Americans like her) flaunt blonde hair, Compendio felt encouraged to take the leap.

“I figured at worst, it'll just not look good. And then like no one will have to see me,” she says.

Before, Compedio’s friends dissuaded her from dyeing her hair pink or purple out of fear of being read as a “streotypical lesbian.” Now, she embraces it.

“Now, if someone tried to say that to me, I’d be like, ‘But I do like girls!’ So I don’t see that as a bad thing,” Compendio says.

_________________________

Luodan Rojas’* hair transformation has quite literally been a journey of self discovery. Just two years ago she had long ombré hair, just like most girls around her.

“This [was] proving: I’m a girl, and other people can see me as that,” Rojas says.

Rojas had what she describes as a typical experience among queer students: coming to college and deciding to chop all her hair off. She cut her hair to her collarbone, and as it got progressively shorter, she also stopped wearing makeup. Slowly but surely, Rojas grew more comfortable with her own androgyny.

“The hair totally kick-started that,” she says.

But for Rojas, the evolution of her style— from hair and makeup to clothes— wasn’t the result of an impulsive night in. She started developing crushes on girls she initially thought of as just friends. With their bobs and baggy pants, they were aspirational to her.

“Even if I didn’t want to date them, I just thought they were so cool and wanted to take inspiration from them,” says Rojas. “It was very gradual … It makes more sense, what I was gravitating towards.”

Changing her hair was Rojas’s way of saying that she was no longer the same girl as before. Four years later, she feels she no longer has something to prove. In fact, quarantine has reminded her of that same introspective time, being “stuck with her feelings.” But this time, Rojas has decided to return to her natural brown hair.

“It just felt like that time in my life had ended, and now I don’t really need it. I kind of just feel more comfortable,” says Rojas.

_________________________

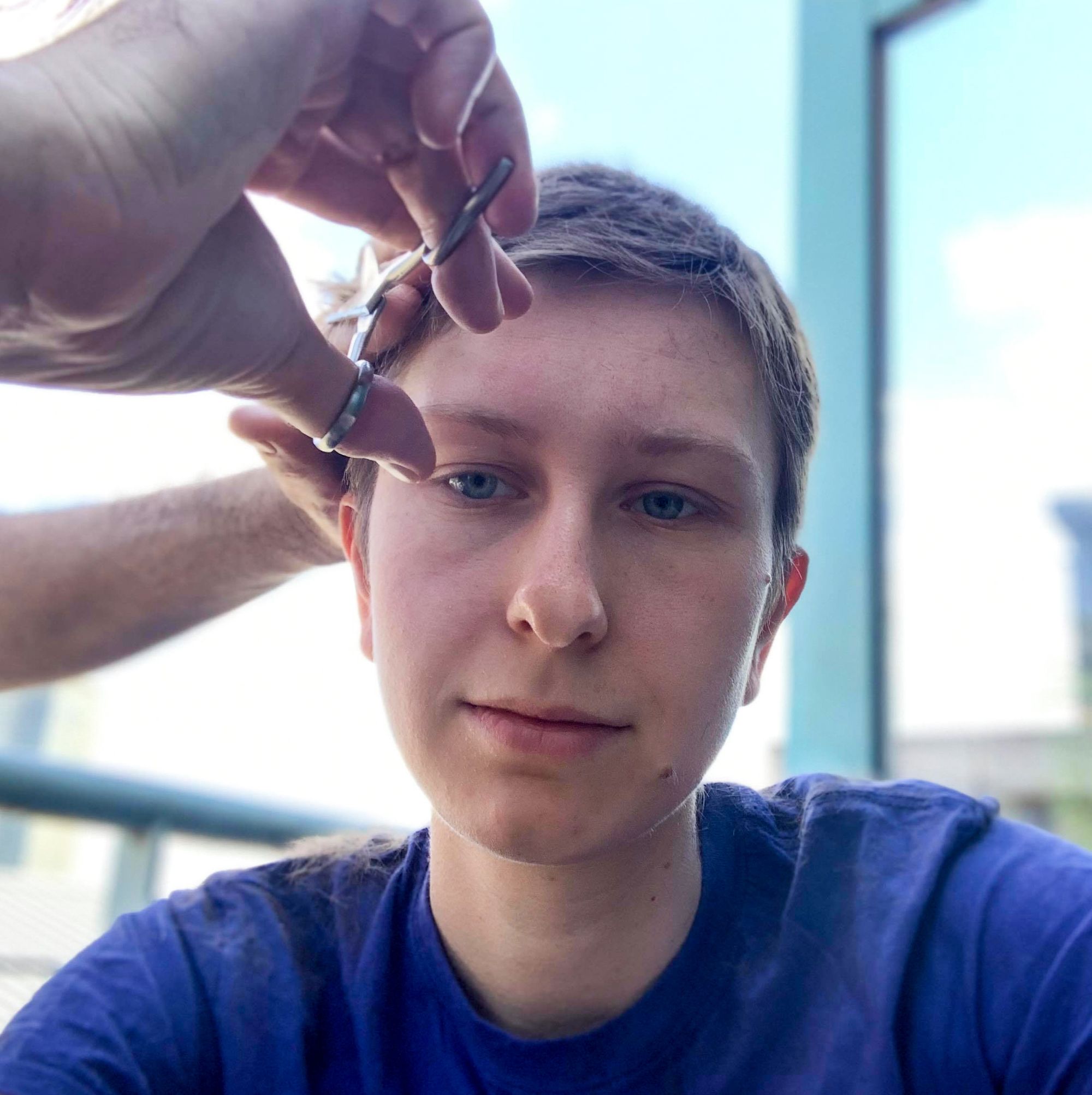

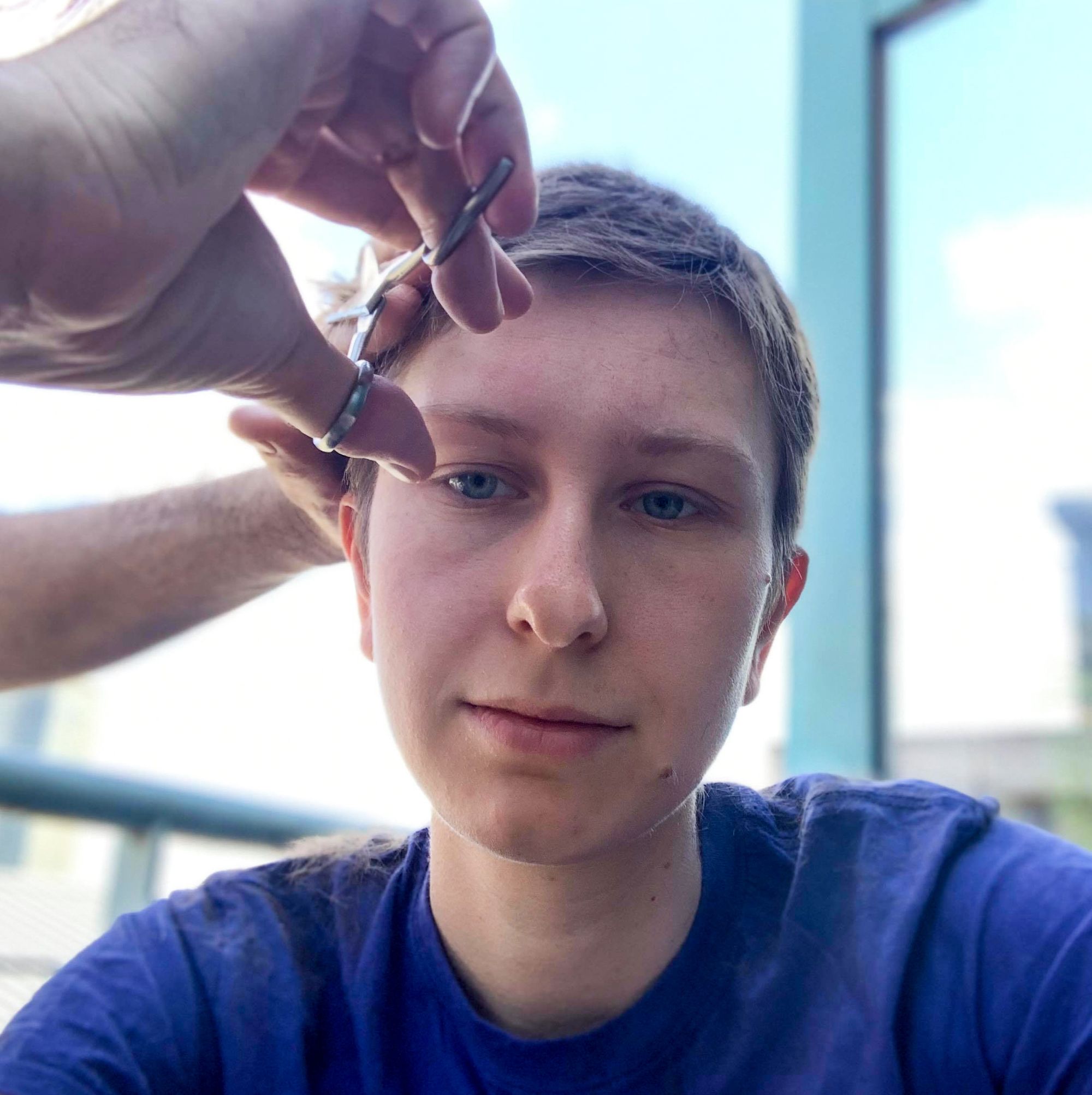

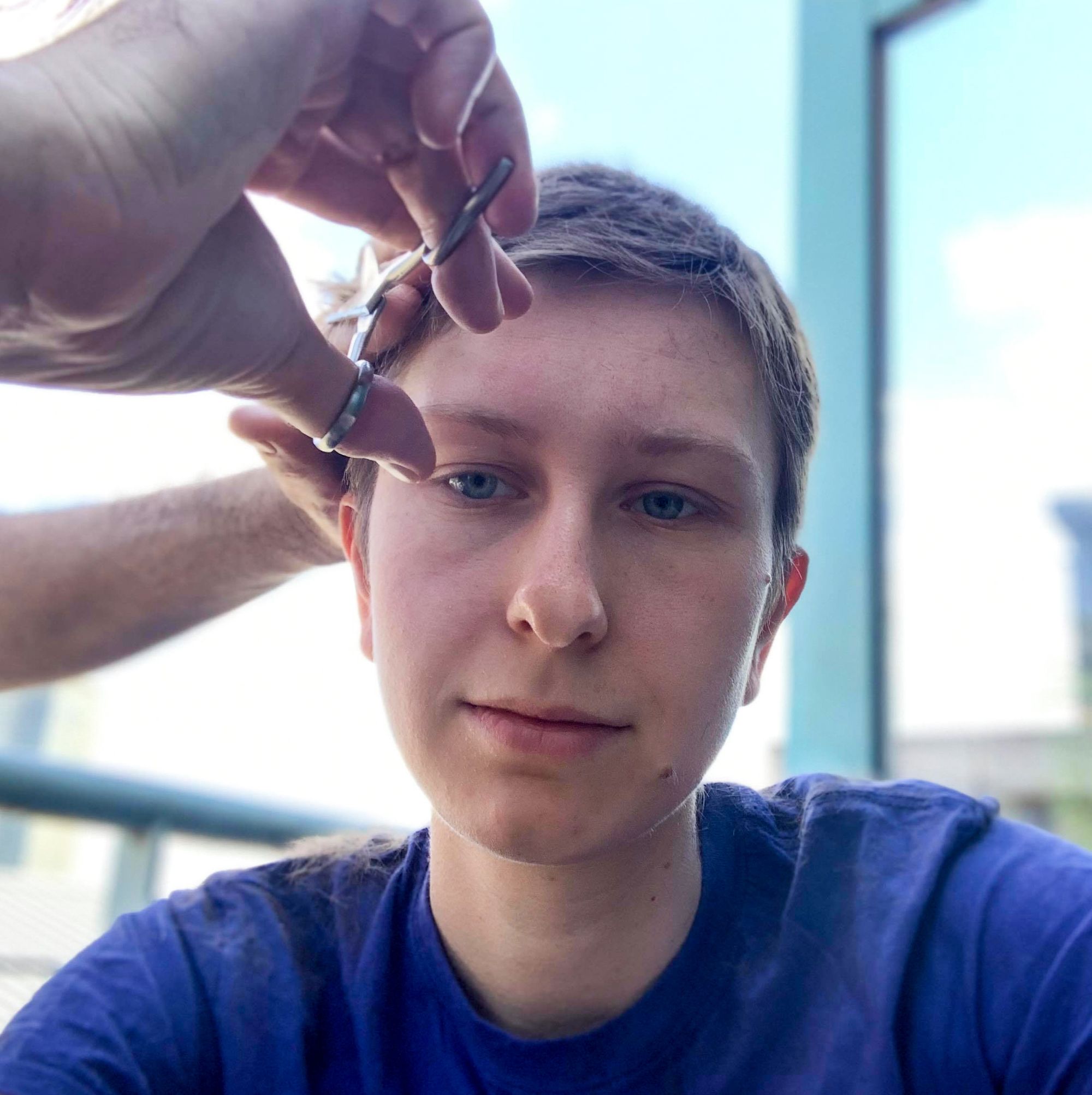

Sitting outside his family home in North Carolina, Amos Pomp drags his fingers through his increasingly shaggy brown hair. In the light, you can see its purple tinge. Pomp holds a strong belief that gay men bleaching their hair is stupid.

“Zac Efron dyed his hair silver or whatever,” he says. “All the ‘Instagays’ look like that. They look exactly the same. And anyway, Zac Efron is not gay.”

Pomp’s opposition is centered on the co-opting of queer aesthetics, as he says these styles are becoming more mainstream. As nose rings, cuffed jeans and bad-at-math jokes sprout like weeds across the internet, there seems to be growing frustration with distinguishing between queer folx and Kristen Stewart fans.

“One dangly earring worn by a dude ... radio people at Northwestern do that. It doesn't mean queerness anymore,” Pomp says. “Signaling to me is like, ‘Oh, I'm coding my behaviour so that you might think that I'm queer.’ But if everyone knows that bleaching your hair means you're gay, then does it mean anything anymore?”

Often this is done under the guise of normalizing queer ways of being, but can set a dangerous precedent. Growing popularity means traditonal queer ways of being aren’t as radical as they once were. But these practices are more than just aesthetic choices: they have been a means of protection and of survival.

“For as long as there are people who are scared to come out, for as long as there are people who face immediate punishment from friends, family or the legal system for coming out — as long as those folks still exist, then there needs to be some sort of marking of difference, signalling and secrecy that they can tap into if they're not comfortable going mainstream,” says Pomp.

*Rojas and Glick are current and former contributors to North by Northwestern.