Inscribed above the front doors of Deering are the phrases “aut libere scribenda, aut scribere legenda,” meaning either to “read something worthy of being written” or to “write something worthy of being read.” Each year, students file in and out of Deering library to fulfill this purpose.

Ninety years ago, Deering opened its doors to its first patrons. A welcome replacement for the previous Lunt Library, now Lunt Hall, Deering continues to stand as a campus landmark and a key embodiment of the Northwestern experience. Students can count on a quiet reading room, a picturesque garden landscape and a rolling meadow to support their studying. In celebration of Deering’s first 90 years of existence, NBN is taking a look back on the library’s long momentous history.

Turning a new page

When built in 1894, Lunt was widely regarded as the finest library in the West. But by 1919, when Theodore Koch became Northwestern Librarian, Lunt appeared dilapidated. Both the University collection and the student body had outgrown the space. Initially built to hold 100,000 volumes, Lunt housed 120,000 when Koch arrived. He immediately set out to improve the outdated library system.

An aerial view of the first floor of Charles Deering Library during construction, taken in 1932.

“Mr. Koch came to the university at a time when our library was poorly organized and rendering only a mediocre service. He at once injected new life into the organization,” Franklyn B. Snyder, Northwestern’s President at the time, said at Koch’s funeral service in 1941. “Indeed, it may be said that he put our library on the map.”

Koch submitted annual librarian reports to the University President, each time noting the desperate need for a new space.

“Thousands of books have been boxed and stored in the basement of Fisk Hall on account of lack of shelf room in the Library,” Koch said in a 1921 report, 12 years before Deering opened. “Books are piled on the floor and on ledges.”

In 1929, Charles Deering donated $500,000, and the University immediately set the donation aside for a new library. Its location would display views of the lake on one side and of campus on the other.

Rebuilding & restocking

The University hired famed collegiate gothic architect James Gamble Rogers to design the library. His previous works included Yale University buildings and Northwestern’s Chicago Campus. Koch chose the gothic style present today.

“No other architectural style, unless it be the Greek, has expressed more adequately the upward reaching of man’s spirit,” Koch said.

Deering opened its doors in 1933. Despite the building’s construction at the height of the Great Depression, it exudes opulence and grandeur.

Sculptor Rene Pail Chambellan completed the carvings featured in the library, like the Northwestern ‘N’ above the reading room. The edifice is comprised of limestone and features 68 stained glass windows, each depicting mythological figures, literary references or historical scenes.

Koch served the University until his death in 1941, overseeing Deering’s construction and the transfer of volumes.

After Koch passed, Effie Keith served as the interim University Librarian. During her tenure, Keith founded the Technological Library and acquired 25,000 volumes. She also oversaw the library during World War II when more students came to Northwestern to train at the Navy’s Midshipmen school.

The enrollment increase is attributed to the initiation of various military-adjacent training programs on Northwestern’s campus. As more men came to live in Evanston to study and train at Northwestern, the library struggled to serve all its patrons with 50% less staff members than before the war.

After the training camps closed and men came home from the war, Northwestern again suffered from overcrowded buildings and struggled to provide housing to returning soldiers. Deering Meadow, outfitted with metal tents, temporarily housed many veteran families.

Expanding the shelves

As time went by, the University library collection grew. In July of 1950, Deering held a ceremony for the shelving of its one-millionth book — presented by Roger McCormick, who placed the first on Deering’s shelves when he was 13 years old. By 1951, books outnumbered Deering’s shelving capacity.

“Its most urgent need is an addition to the building,” The Evanston Review wrote in 1951. “This not be an airy dream but a concrete necessity if Northwestern is to fulfill the purpose for which it has been shaped during a century’s growth and development.”

In 1967, Northwestern received a donation totaling $4.1 million, given by the Engleheart family. With this donation, Northwestern hired Walter Netsch and the firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. Architectural designs and expansion plans began. University Library, also known as Main Library, would be built with an underground attachment to Deering.

“The three towers of the new Main Library, opened in 1970, emphasized the antiquity of Deering’s design while also usurping its status as a state-of-the-art library; this newcomer was the library that would see us into the electronic age,” Janet Olsen says in her book Deering Library: An Illustrated History.

Main was an architectural gem at the time of its construction. The brutalist style had become popular during the mid-20th century, and its strikingly modern design garnered praise. John McGowan, then University Librarian, described Main as “a distinguished building of rare architectural merit.”

“The new library had as much vision, theory and passion behind its planning as had gone into Deering, with a result totally different — reflecting the aesthetic of the times, advances in technology, and new interpretations of the purpose of a library,” Olson writes, highlighting the juxtaposition of styles between Main and Deering libraries.

A new chapter

Even with Main’s construction and development, Deering was far from forgotten. Just months after Main’s opening ceremony, anti-Vietnam War protestors used Deering as their backdrop. After the tragic Kent State University shootings, anti-war students at Northwestern organized massive demonstrations on Deering Meadow.

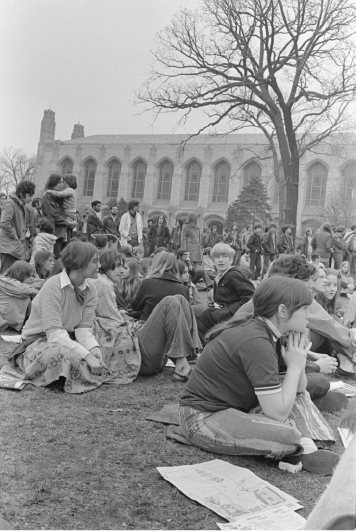

During May of 1970, students held mock funerals on Deering Meadow and heard from various speakers, including Eva Jefferson Paterson, a Northwestern student and famous activist. Almost 4,000 people attended daily protests at the site. Often an event locale or common meeting place, the area housed anti-Iraq War protests in 2003 and a mental health awareness exhibit in 2015.

Students gather on Deering Lawn for an anti-Vietnam War protest during the 1970s.

Mock graves placed on Deering Lawn in Matyof 1970 for soldiers in the Vietnam War.

More often, however, Deering and Deering Meadow host student celebrations, homecoming pep rallies and club pick-up games. You can find dogs frolicking outside on the lawn and students hunched over computers inside, cramming for exams.

Every fall, new students “March Through the Arch” and find their way to a ceremony on Deering Meadow, marking the beginning of their Northwestern career. Every spring, the Northwestern convocation takes place at the same spot.

The ceremony has hosted notable figures like the late Supreme Court Justice and feminist icon Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 1998, former President Barack Obama in 2006 and alumnus and comedian Stephen Colbert in 2011. Students sit with family and friends, waiting for their hard-earned moment of walking across the stage and receiving their Northwestern diplomas.

Deering is where students gather to shape their Northwestern experience — in the past, present and future.