Snagging an internship at Cartoon Network for last summer was relatively straightforward for Scarlett Machson. The Communication junior simply applied on the Turner Broadcasting jobs website – no networking finesse necessary. A few months later, she submitted a video interview to the company.

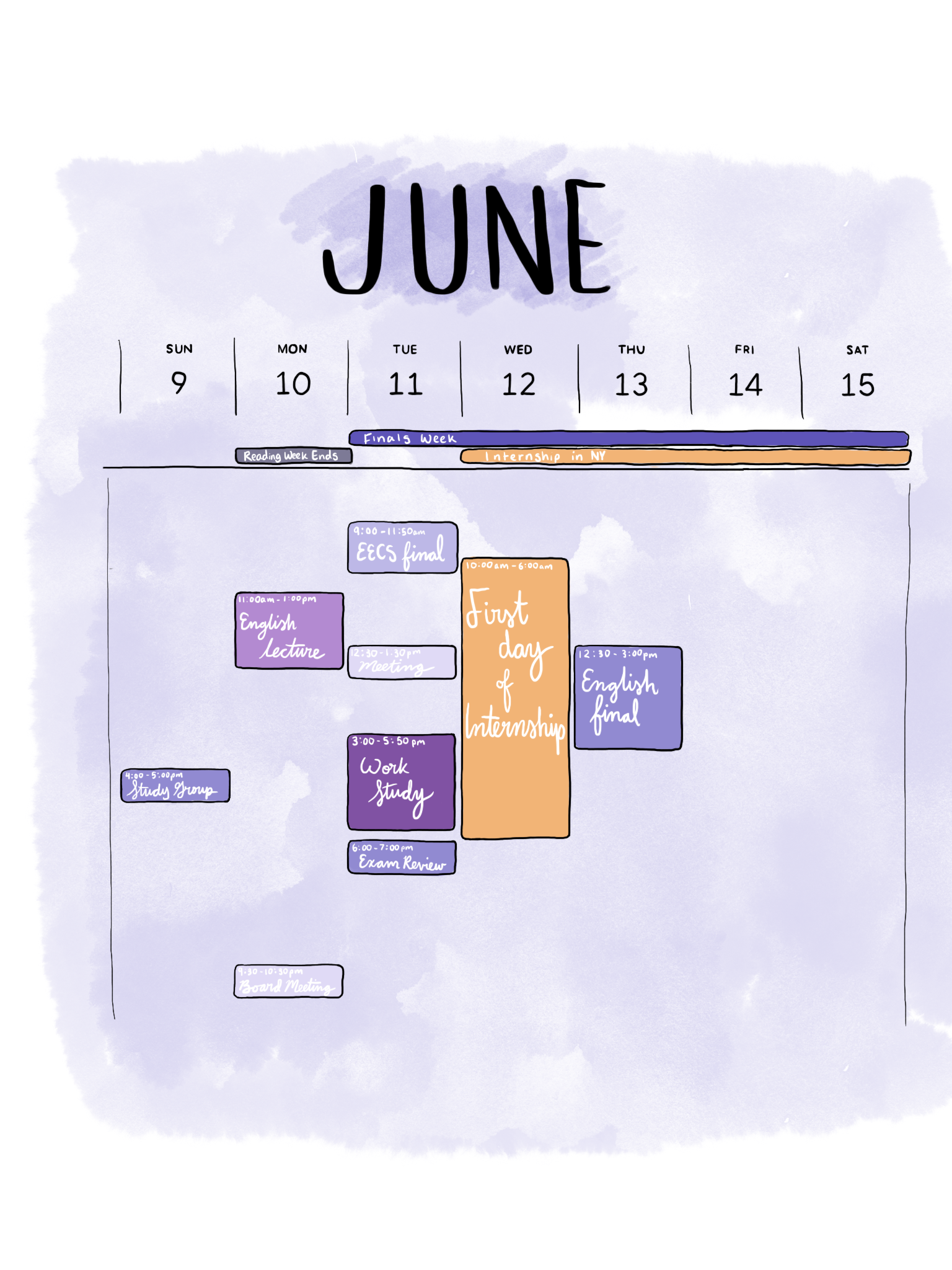

Things got tricky after Cartoon Network told her she landed the job. The issue? Her planned Spring Quarter finals schedule conflicted with the mid-June internship orientation. Machson found out she got the internship a few days before spring break – a pretty early notification time for the industry, she says, but long after she’d registered for her courses. She planned to take an accounting class for her Business Institutions minor, but over the break, the professor told students that they must be on campus during reading week for a mandatory group presentation.

That wasn’t happening, so Machson dropped that class for another on business strategy. She took the final early by working out business problems during an informal discussion with her professor. “It was a little more stressful than just sitting for an exam because it was kind of on the spot with him looking at me, asking me questions,” Machson says. “But I was obviously happy to do it if it meant I could do the final.”

Northwestern notoriously uses the quarter system, which pushes back the school’s start date into late September and ends the academic year in the middle of June. The University cites benefits including students’ ability to take more classes than they would on a semester schedule. However, the system can cause problems for students applying to jobs or internships with strict start dates, since most of the rest of the world doesn’t run on Northwestern time.

Over 70% of schools were on semesters as of 2012 – so while Northwestern isn’t alone in having quarters, it’s not a common practice. University officials discussed switching to a semester system in 1996, but Northwestern is currently committed to maintaining the quarter system according to Robert Gundlach, a linguistics professor who co-chairs the Provost’s Academic Calendar Advisory Group.

Provost John Holloway formed the group, which can only make recommendations, to navigate the execution of three calendar changes approved in principle at a May 2017 faculty senate meeting; he retains the final say on calendar policies. The approved changes include moving up commencement by shortening Senior Week, returning to classes the Tuesday after spring break and implementing “final exam flexibility.” The group is also exploring more options for the calendar that it believes could optimize student experience.

“I think there's some excitement about other possibilities [that] sort of fit into the quarter system,” Gundlach says. “That comes up once in a while, and I think that's come up again: How to do this.”

They come in threes

Provost Holloway appointed Gundlach and Industrial Engineering Prof. Karen Smilowitz to head a new advisory group on the academic calendar last August. They come from drastically different disciplines, which was intentional: Holloway chose Smilowitz for her logistical skill, since she manages complex systems as an industrial engineer. Gundlach, on the other hand, represents a more qualitative point of view.

With how fun their last names sound together, plus their complementary expertise, you might imagine Smilowitz and Gundlach would be off solving zany mysteries if they weren’t heading the provost’s calendar committee. Instead, they lead people from across the University in exploring calendar adjustments and planning how to best implement the three approved changes. The group includes staff from the Office of Change Management and Division of Student Affairs along with faculty and staff representatives from the various schools.

The first two changes will become reality in 2020: shortening Senior Week to move graduation earlier in June and beginning Spring Quarter on a Tuesday treated as a “Northwestern Monday” (we all know how confusing those can be). Smilowitz says these were less contentious adjustments. Final exam flexibility requires more thought – according to the minutes of the May 2017 faculty senate meeting, it could involve remote or early proctored exams that were not officially allowed in the past, at least at the undergraduate level.

“What became clear to us is that there were certain data that needed to be collected,” Smilowitz says of the process for enacting the change. “I think that there's a lot of support for exam flexibility, but the more you dig into it, it's really hard.” That’s partially because Northwestern’s six schools, and even the departments within, have their own ways of conducting exams based on what works best for the discipline.

Smilowitz and Gundlach mentioned Kellogg’s use of self-scheduled (but still proctored) exams during the weekend before finals week as an example of already implemented exam flexibility. This process initially helped Kellogg students going abroad for curricular spring break programs finish their Winter Quarter exams early. It also alleviates scheduling conflicts that, similar to Machson’s, occur at the end of Spring Quarter when students need to leave in late May or early June to begin internships.

“The Winter Quarter need is very discrete, I think, and unique to Kellogg,” says Lesley Kagan Wynes, the school’s assistant dean for academic experience. Other undergraduate programs like the Kaplan Humanities Plunge and Medill Global 301 classes travel after Winter Quarter, but only during the formal weeklong break. “The spring [issue] is maybe a little bit more widely applicable to students in other programs,” she continues, “but we were solving sort of discrete problems that we had.”

Still, Wynes says what Kellogg does is “likely not scalable beyond a population of our size,” given the amount of work it takes to administer exams in such a way. Those exams have to be counted, sorted and put in the correct rooms, and proctors have to be trained and hired, all on top of managing the exams still given on the standard schedule.

But not all final exams happen during finals week, and you probably know that if you took Spanish to fulfill your foreign language requirement. Many classes have various written and oral exams throughout the quarter, without any tests during proper finals week. According to Spanish Prof. Heather Colburn, former director of the Spanish Language Program, this facilitates the department’s pedagogical approach to teaching language: assessing in smaller, more manageable blocks.

“We usually don't use the term ‘final’ because that term usually conjures up ideas of a long, cumulative exam,” Colburn said in an email. “Because our elementary and intermediate courses are sequenced, and because of aforementioned language learning/assessment, that type of assessment is counterproductive for language learning.”

Despite this built-in flexibility in Spanish classes, one of Machson’s main issues with leaving campus early for her Cartoon Network internship was needing to take her Spanish oral exam earlier than its set date. Eventually, she figured out a one-on-one exam with her professor.

Because of her experiences, Machson says she thinks professors should be open to work with students' schedules given the trickiness of the academic calendar. “I think the best thing would just be to ask the professors to be available in their office hours to give the finals, and to have the finals written well in advance,” she says.

Communication junior Tommy Li had a more creative way of reconciling his internship schedule with the Northwestern calendar. He started working at Marcel Digital, a downtown Chicago marketing agency, during the first week of his freshman Spring Quarter. He worked out his spring class schedule, a full load of four courses, so that he went to class Monday, Wednesday and Friday and commuted into Chicago for work on Tuesdays and Thursdays.

That worked fine until the end of the quarter, when he had to move all his belongings out of his dorm and take finals that didn’t align perfectly with his usual class schedule. “I just had to not go to work that week, and they were kind of understanding because … I had already communicated that I wanted to be there over the summer,” he says. “It was definitely messy and it could have been better for sure.”

Individual experiences aside, Holloway says although it may sound hard-hearted, the quarter system is not “an unknown factor when students apply to Northwestern.” Yet some first-generation college students, unfamiliar with the ins and outs of student life and often unable to visit Northwestern until after they're admitted, accept their admissions before knowing what the quarter system means.

“There’s no doubt that there are summer opportunities that are missed because of the quarter system, and that’s regrettable,” Holloway tells North by Northwestern. “At the same time, it’s not at the level of system-wide crisis. It’s at the level of individual frustration, which I respect, which is real, but that’s something quite different.”

So when will exam flexibility go into effect, anyway? Great question. The advisory group is currently looking at surveys administered to faculty members throughout the fall and winter to gain a sense of how they actually give (or don’t give, shoutout PSYCH 204) their final exams. The academic calendar FAQs page only says Northwestern will test various flexibility initiatives in the 2019-20 academic year before fully implementing any of them.

Cracking the (honor) code

When Holloway came to Northwestern at the beginning of last school year, he saw that the University lacked something his undergrad institution, Stanford, had: an honor code. Adding a day to spring break and shortening Senior Week are easy fixes; that’s why they’re going into effect so quickly. Coordinating exam flexibility will be more challenging, and Holloway thinks an honor code could help.

“We have an excellent registrar, Jackie Casazza, and she said the only way to make this happen is that you move away from proctoring exams and you create the ability for people to take exams remotely,” Holloway says. “We have the technology to do all the stuff, but we need to have a culture shift. And in order to do the culture shift, have an honor code that gets people removed from the classroom, students are on their honor.”

At Stanford, Holloway says, exams weren’t proctored and students held each other accountable. Cheating is always going to be an issue, he acknowledges, but proctoring won’t even solve all of those problems – and students will be tough on each other.

“I think it's just an important articulation of an ideal,” Holloway explains. “So this was not even part of my agenda. I was just trying to complete a process that started before I came, but when registrar Casazza said we'd have to have an honor code ... it's one of these weird coincidences that a calendar change [can] actually [accomplish].”

Smilowitz confirmed in an email that the advisory group has been alerted to the possible need of an honor code. While actually implementing an honor code falls outside the group’s duties, she said, the group could make a recommendation to the provost to further explore an honor code.

Machson thinks the benefits an honor code would bring by making it easier to take exams would outweigh the risks of cheating. “We're Northwestern students,” she says. ”We should be trusted with taking tests with integrity, not treated like children.”

But Li isn’t as enthusiastic. He recognizes that his opinion is influenced by the fact that he had a flexible employer who let him adjust his work schedule for exams. An honor code “would make people's lives easier,” he says, “but I would definitely be worried that people would try to take advantage of it.”

D-termining more changes

The suggestion of a December term – D-term if you’re nasty – drummed up attention and excitement when The Daily Northwestern reported it in November. Online information merely says the D-term “would take place between Fall Quarter and Winter Break.” At other schools, this optional shortened term functions as a time for students to take intensive or experimental classes, sometimes involving travel, within the space of a few weeks. It also appears in January, as a “J-term,” at some schools like Loyola Chicago and New York University.

Schools with these intersession terms are usually on semester schedules, as Smilowitz notes. “Obviously semesters have a flexibility in January that we don't,” she says. “There is a lot that's exciting about having these co-curricular, more individualized experiences.”

Universities that use the quarter system and have D-terms include DePaul, which currently has a task force in place to explore the switch to semesters, and Lawrence University, a private liberal arts college in nearby Appleton, Wisconsin, with three full “terms” that mirror Northwestern's quarters.

Lawrence Associate Dean of Faculty Bob Williams says the school’s trustees decided years ago to shift the beginning of the academic year to earlier in September and end fall term at Thanksgiving, with a break from then till the new year. The trustees reasoned it would be easier and cheaper for students to travel home for Thanksgiving and stay through the new year, rather than returning to school for fall exams and leaving again in December. They also aimed to reduce costs by having fewer residence halls open and reducing staff hours during the break.

In practice, the strategy wasn’t cost-effective, according to Williams, since in-season athletes and international students still had to be on campus for some time. Still, a survey showed that Lawrence preferred ending at Thanksgiving, so a working group proposed a two-week December term to make use of the extended break.

Five years later, Lawrence’s D-term appears to successfully engage students. Only 28 students took five classes in 2014, its first year. The most recent intersession had 54 students – almost double – across six classes. (And that's big, considering Lawrence only has about 1,500 undergraduate students total.)

It’s not hard to guess why: Previously offered D-term courses at the school include a Shakespeare intensive, a course on the history of video games and an archival discovery course. Others travel internationally to places like London, Buenos Aires or cities throughout Greece, while some on-campus courses take shorter weekend trips to places like Chicago. The extended break gives travel time for fall-term classes as well.

“The important thing is that it should be some sort of experiential learning experience, hands-on, that is different from what you would do during a regular term,” Williams says. “We don’t offer any of our regular-term courses in December term.”

With hypothetical possibilities like this, a restless Northwestern student like yourself might want to take a D-term class instead of sitting at home for a month over winter break. But Smilowitz and Gundlach stressed that it would be remiss to imagine a D-term as the main possible calendar change, and they didn’t endorse any sort of additional term just yet.

“I'm hopeful that some really interesting ideas are going to come out of this reflection, whether they take the shape of a single place like a December term, or whether that opportunity would really fit well in the summer, or in the spring,” Gundlach says. “You might get something actually with more flexibility and more richness of possibility.”

Even more recently, the advisory group has taken a new direction in discussing options for the fall. Holloway mentioned some mysterious, unnamed idea that makes “compelling sense, [with a] really interesting logistics challenge related to it.” Smilowitz confirmed this in an email. “There are many significant challenges with the structural calendar changes that would be needed to implement D-term,” she said. “Therefore, we are exploring ways to expand innovative co-curricular opportunities for the university that could avoid these structural calendar changes.”

So don’t hold your breath if you’re dying for a D-term – according to Holloway, the earliest any Fall Quarter change could go into effect would be 2021, and by then many of us will probably be unemployed freelancers or soulless consultants.

In the meantime, Northwestern students can only do their best to work with what we’ve got. After last summer at Cartoon Network, Scarlett Machson doesn’t know what her plans for this year will be – she’s applying for more TV and film internships, and expects start dates to be an issue again. But this time around, she’s more worried about a conflict with the premiere of her media arts grant-funded film the weekend before Reading Week. Even taking final exams early can’t fix that.

“I think going forward, at least for me, I won’t necessarily leave school early just for the sake of being there on time for the internship,” Machson says. “Depending, of course, on how cool my supervisor is.”