Students reflect on their path to recovery and normalcy after mental health crises.

*CONTENT WARNING: This story discusses in detail the experiences of students who have been hospitalized due to severe mental illness and suicidal thoughts.

Seconds later, I threw on my coat, grabbed my phone and raced to Searle. I ran with my coat half-zipped and shoes untied. Across Sheridan Road. Down Emerson Street. Up the concrete steps. Into the Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS) lobby.

I was ushered into the tiny office where my friend Mia Hodges was directed by Northwestern to see a CAPS therapist. It was small, with just enough room for me, Mia and the therapist. She had clearly been crying, but she hid it behind a smile. Mia has been one of my closest friends since I came to Northwestern, and I knew her well enough to see how fearful she was. I smiled back, pulled up another old paisley-patterned chair, and we waited. We talked as if nothing was wrong, because that’s what you do when you can’t think of anything else to say. I had no idea how to address the weeks of deep depression and suicidal thoughts that had landed Mia in that CAPS office in the first place.

The inpatient psychiatric ward at Northshore features what amounts to a “revolving door” of Northwestern students.

We had lapsed into silence by the time two Northwestern University Police Department (NUPD) officers came to take us to the hospital. Neither of us had been in the back of a police car before, sitting on those cold, black plastic seats. Despite their amiable smiles and apologies for the car seats and harness-like seatbelts, the police officers were there to make sure my friend couldn’t escape. How many students had they ferried to the hospital like this?

I waited with Mia at the hospital for the next six hours. We watched this horrible reality TV show, Chrisley Knows Best, as a steady stream of doctors and crisis counselors asked Mia to retell her story and recount her sadness over and over again. A hospital security advisor came in and packed all of Mia’s belongings in sterile plastic bags, logging each item including her phone and laptop, essentially making me her only lifeline to the rest of the world: family, friends, coworkers. I called her parents and cried with them. I called my mom, who cried with me, too. I had class in the morning, and we were still waiting in emergency triage at 11 p.m. But academics paled in comparison to this. I was constantly harassing the hospital staff: How long will she have to wait here? Can you please get her dinner? Where are you keeping all of her possessions?

Finally, around midnight, the immense hospital cogs finished turning. The barrage of hospital staff decided that Mia, who still kept her smile plastered on tight, needed to be on 24-hour suicide watch and stay in the psychiatric ward until further notice. I promised her that I would stay the night and sleep next to her, so she wouldn’t wake up alone. But when a nursing assistant helped her into a wheelchair and began to push her away, another nurse came over and thrust herself between us. She told us visitors’ hours the next day were from 6 p.m. to 7:30 p.m. No more than two people at a time.

With that, the electronic doors swung shut and locked with a loud click. I watched through the little glass window as they rolled Mia down the hall, totally alone, and cried.

Roughly half of all lifetime mental disorders begin by the mid-teens, and three-fourths by the mid-20s, according to a widely cited 2007 Current Opinion in Psychiatry study. Without effective preventative mental healthcare, these disorders can remain untreated, and the most serious illnesses can potentially reach their most alarming symptoms: suicidal thoughts and actions.

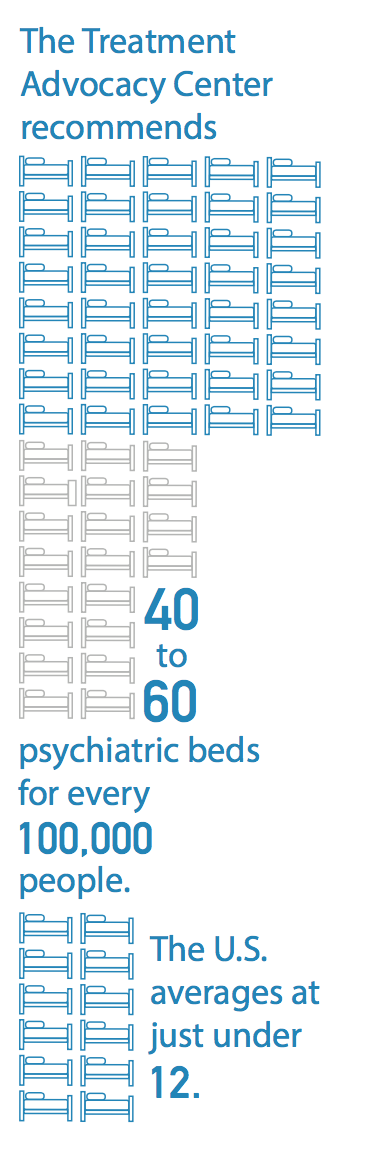

Many sufferers find the first step in getting care the hardest, according to Dr. Susan McClanahan, the chief clinical development officer and founder of Insight Behavioral Health Centers. Because of this hesitancy, mental illness can reach dangerous levels before care is sought, and at that point, inpatient psychiatric care is required. The number of people who need in-hospital care consistently surpasses hospitals’ capacity to care for them. The Treatment Advocacy Center recommends 40 to 60 psychiatric beds for every 100,000 people. The U.S. averages at just under 12. The waiting period that ensues has already hurt my family, and it has undoubtedly hurt others.

Being on suicide watch also creates a financial burden. Northwestern Health Insurance (NU-SHIP) funds 80 percent of inpatient medical treatment. While this covers a sizable amount, it simply doesn’t cut it for some low-income students. Others would prefer or need to keep their mental health issues private from their parents and must cover the cost alone. According to a 2012 study from the U.S. National Library of Medicine at the National Institutes of Health, a stay of between four and 11 days in the hospital for inpatient psychiatric treatment can cost anywhere from $4,000 to $9,000. And some people are encouraged to stay in intensive treatment for a full month at offsite locations with similar prices. The costs vary widely based on the medications required, condition upon entering the hospital and length of stay, among other factors.

When students seek help from or are reported by faculty, staff or other students, CAPS sends them to Evanston Northshore Hospital for emergency services if they are deemed a severe danger to themselves. The inpatient psychiatric ward at Northshore features what amounts to a “revolving door” of Northwestern students. Mia told me the staff quip that when one goes out, there’s always another to take their place.

McClanahan says that at Insight’s Chicago facilities, “There’s probably never a time when we don’t have some Northwestern students.”

Every quarter, CAPS sends 15 to 20 Northwestern students to the hospital directly, according to CAPS Executive Director Dr. John Dunkle. This figure does not include students who get to the emergency room themselves, or who are referred by their off-campus mental healthcare provider. The presence of Northwestern students in both the inpatient psychiatric ward at Northshore Hospital and the residency program at Insight is constant.

“By virtue of working at Northwestern, where we have more traditional age college students ... they’re going to be at a higher risk for the first onset of major depression or bipolar,” Dunkle says.

McClanahan notes that while Northwestern students are common at Insight’s Chicago facilities, mental illness often manifests itself in early adulthood first, so college students in general constitute a large percentage of intensive psychiatric cases. McClanahan says the prevalence of mental illness, too, has increased significantly in the past decade.

“There’s no question if you look at the data on depression and anxiety,” McClanahan says. “This is a generation that is suffering more than any has in the past ... I think we are seeing partially the effects of the impact of social media and technology on young people, and people are really struggling.”

Just over a year ago, during fall quarter of his sophomore year, Saul Osorio walked into his Weinberg advising appointment to talk about dropping down from three classes to two. His adviser suspected something was wrong and walked Saul to CAPS for an emergency meeting.

“Bless her heart. She is amazing,” Saul says, remembering how his adviser was one of the few people who knew what was going on with him at the time.

After waiting for 30 minutes in the CAPS lobby, Saul finally met with a therapist, who told him he could either pay for an Uber to the emergency room, or NUPD could drive him there. Not wanting to pay for the trip to the hospital, he opted for the police escort.

Over the quarter, Saul had isolated himself from his friends, and he took the police ride to Northshore Hospital alone. Four or five hours, a doctor, nurse and crisis counselor later, Saul was given another set of alternatives: he could check into the hospital’s inpatient psychiatric unit immediately, as Mia did, or set up a meeting with Insight at one of its multiple Evanston and Chicago locations.

He chose the latter. After setting a time for the call, the hospital staff let Saul go, and a police officer brought him back to campus. From there, he had to go about applying for medical leave, packing up his dorm room and figuring out insurance.

The process of applying for medical leave is an arduous one, especially when you already suffer from a crippling mental illness that requires intensive psychiatric treatment in a residential facility.

“They did not have a bed open right away, so I had to wait another week till I could move in,” Saul says. “But that was actually a good thing, because I had to go through the whole leave of absence application process anyways.”

While he was busy applying for leave, he got a call from Insight. They had a room available, and he either could accept it immediately or they would give it away to someone else. At that point, Saul didn’t even know where he was going to store the contents of his dorm room. He hadn’t yet finished his paperwork, talked to a Student Assistance and Support Services (SASS) dean or met with his adviser. He had to turn down the room and pray that another one would open up when he was ready.

Throughout this process, Saul says he felt alone.

“Nobody knew. Nobody but [my adviser, SASS dean and a CAPS counselor] knew I was going to go on this leave,” Saul says. “I wasn’t on suicide watch even though they felt that I was bad enough that I should be in residency. They didn’t take the initiative to think this kid might do something crazy in the week that he’s not in residency.”

Saul, however, was lucky. Another room did open up, and he was able to receive care from Insight before he could do anything dangerous. However, as hospitals become more swamped and the number of inpatient psychiatric beds decline, many hospitals resort to turning patients away, according to a 2018 NBC News report, and not all patients are able to follow through with additional care.

Northwestern relies on a system of students, staff and faculty reporters to get students the help they need, according to Northwestern Dean of Students Todd Adams.

“There’s not just one office, and I think that’s on purpose. However someone comes in, you want to meet them at that point.” Adams says. “It could be that they show up at Health Services or CAPS. It could be that it’s through a referral to the Dean of Students Office; it could be an academic advisor, or Student Enrichment Services or a chaplain.”

Legally, the terms “mandated reporters” or “mandatory reporters” commonly refer to people who work with minors, dependent adults or the elderly (those characterized as “vulnerable”) and are required to report any instances of abuse they suspect or are told about. Federal law obligates Northwestern faculty, staff, child care volunteers and some student employees to serve as mandatory reporters. When referring to their responsibility to report students at risk of self-harm, Resident Assistants and other student employees often misstate their status as mandatory reporters. In fact, mandatory reporters are only required to report the abuse of minors at Northwestern; they are not legally obligated to report students over 18 years old for mental health concerns.

In place of a legal obligation, Adams explains that getting help for struggling community members is part of a “community expectation” of all Northwestern students and faculty.

“I would expect you to help another student get access to care or a referral to figure out what the next step might be,” Adams says. “If we’re a community of care, we take care of each other, and that includes helping get people connected ... if that’s making a referral, or actually walking with them, or helping them make the call or getting online to schedule an appointment.”

Both Mia and Saul were referred to treatment, neither of them taking that first step to get help by themselves. McClanahan recognizes that taking the first step in getting help is often “incredibly hard,” and following up for care is just as difficult.

“I think there has to be a bit of trust and a leap of faith that there’s hope out there,” McClanahan says. “We try to hold that hope for [people] even when they don’t have hope themselves. That’s a big part of our job.”

After a quarter and a half of medical leave, Saul wanted to come back to school and pick up where he’d left off for spring quarter. He approached the CAPS psychiatrist who initially refused his request to come back to school and managed to convince her to sign off on his return from medical leave.

“Thinking back on it, I was ready to come back because I didn’t want to be home anymore,” Saul says. “I was not ready for the academics. I was not ready.”

What happened next was essentially a repeat of fall quarter. Saul dropped down from three to two classes and was nearly kicked out of student housing because he became a part-time student, which technically violates the student housing contract. He stopped taking his medication and failed both of his classes for the quarter. “I’d fallen back into those old habits,” he says.

Adams says when a student returns from hospitalization or medical leave, they are provided with a SASS dean who meets with them and ensures continuity of care once back at Northwestern. But there is always the danger that a student will regress in their treatment and, essentially, relapse.

“Somehow with the mood and anxiety we’re still in, what I consider, an old-fashioned paradigm of crisis stabilization,” McClanahan says.

“This is a generation that is suffering more than any has in the past.” - Dr. Susan McClanahan, chief clinical development officer and founder of Insight Behavioral Health Centers

McClanahan says that a more long-term residential program, on average 30 days, allows patients to “marinate” in the changes that they must make to their lives and attitudes in order to stay on course with treatment. Saul could only afford to stay in the residency for one and a half weeks for insurance reasons. The ultimate goal is to get patients back to their regular lives as quickly as possible, McClanahan says, but investing more time earlier on may result in more lasting changes, similar to prevailing philosophies surrounding substance abuse treatment or eating disorder rehabilitation.

The doors clicked shut, and I watched Mia roll down the hallway and out of my view. After twisting through numerous corridors, going up one floor in a side elevator and wheeling through two sets of electronically locking doors, the attendant led Mia into a small, isolated room.

There, a nurse strip searched her body for cuts or marks — any wound Mia could itch or reopen. They gave her new clothes and slippers; she could only wear stretch-band pants, t-shirts and laceless shoes. After her confiscated belongings were searched, any items deemed safe were placed back in her room.

It was small, around the size of a dorm single. The walls were white plaster with no protrusions, and the room had little furniture. There was a small window in the door with a piece of paper taped over it that a nurse could flip up when making rounds. Mia was exhausted, but she took a shower anyway in a little alcove that didn’t have a door so the nurse could still see her. Finally, the weight of the past several months, and indeed many years, caught up to Mia, and she fell asleep.

Looking back on the seven days she spent in the intensive psychiatric ward, Mia says for the most part, she liked it there. There was no academic pressure or family stress to worry about. She even made friends with other young adults in the ward. She had a strict schedule, and she followed it.

But there were other harder times, like when friends came to visit during the one-and-a-half hour visiting period, or when they called on one of the psychiatric ward’s two phone lines.

“After friends would come, I would burst into tears. After and during calls,” Mia says. “That was when I realized I was in a friendly prison ... I couldn’t really see them or be with them.” But Mia, like Saul, felt that getting help was the best choice she could have made. It was what she needed to do. “When I came out a week later, I was so much better,” Mia says. “I didn’t realize how bad it was until I was actually better.”

If you or someone you know is experiencing suicidal thoughts or a mental health crisis, please call the Northshore Hospital crisis number at 847-570-2500 or the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255.