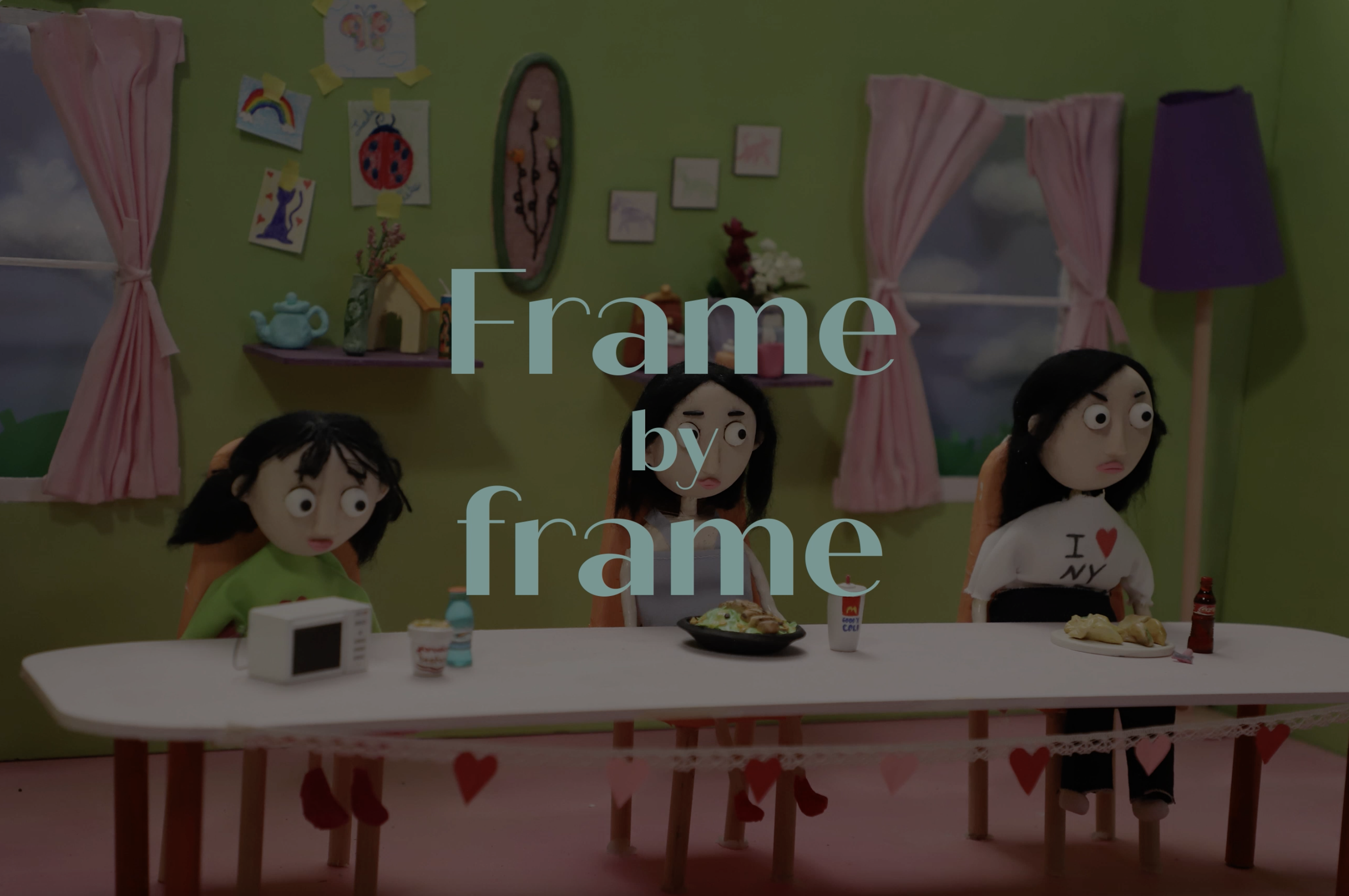

Three puppets sit at a dining table. One swings her feet back and forth. Another shifts her eyes side to side. The third gives a dramatic eye roll. This short scene covers about four seconds of stop motion film [Shelf Life’s] ten-minute run time, but is composed of dozens of frames — pictures taken between incremental tweaks of facial features and limbs — compressed together to mimic movement.

Communication fourth-year Erin Zhang received a Bindley Grant to direct [Shelf Life] in May 2021, over a year before the film is set to premiere. The $5,000 grant, given to two student directors by Studio 22, a student-run production company, allowed Zhang to explore the themes of food consumption and the expectations that society places on people — specifically women — with a “humorous twist.”

The puppets representing the younger ages of the main character.

“I was mostly inspired by this realization of how much women talk about food,” Zhang says. “When I was thinking about feminine habits toward eating, it’s really easy for negative attitudes to cloud something that is really positive and socially uniting like food consumption.”

Stop motion is a labor-intensive filmmaking technique where figures are gradually moved between photographs. When all of the photographs, or frames, are played together, it creates an impression of movement. In [Shelf Life], 12 frames make up each second of Zhang’s film. Zhang’s love for stop motion stems from her fascination with museum dioramas, which she describes as self-contained worlds that are entirely created by the artist.

“To walk into this little space that’s completely artificial but feels so real and you have control over every single thing, that’s what is really exciting about stop motion,” Zhang says. “If I didn’t like that one piece, I can change the color. I can cut it up. I can destroy it.”

Erin Zhang, director of Shelf Life.

[Shelf Life] is Zhang’s third stop-motion production; she’s worked on two shorter films in the past. Stylistically, she cites Wes Anderson as a huge inspiration, particularly his intricate food scenes, which influence [Shelf Life’s] focus on eating. Thematically, Zhang draws on her personal Asian American heritage when exploring food’s role in familial relationships.

“I’m sure other Asian Americans, especially women, can relate to this idea of your mom really caring about you when she’s like, ‘You’re getting fat’ or ‘You need to stop eating,’” Zhang says. “It’s very culturally significant, but thinking about it from a Western perspective, it can be hard to hear stuff like that growing up. I wanted to explore that because I know that’s relatable for a lot of people.”

Within the basement of St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, a scene emerges in vibrant contrast to the wooden pews above. The basement’s walls are painted bright shades of lime green, turquoise, orange and mauve, with handprints and doodles scattered all over them. On one side of the basement are tables filled with sets and puppets, framed by studio lighting and a camera. The other half is primarily taken up by an arrangement of couches.

Fourth-year Erin Zhang, setting up set for the final days of shooting.

“The tone of this film is nowhere near ordinary,” Communication fourth-year Tej Narayanan says from a couch. “It’s very clinical. It’s very surreal, but there is hidden emotion lurking beneath the surface. It’s really kind of evoking the hidden anger of what this story is trying to show while also making it seem like a genuine authentic guided tape, like the kind that you would see right in the ‘70s and the ‘80s.”

As [Shelf Life’s] gaffer, Narayanan focuses on ensuring that the set’s lighting is consistent between takes. Even a slight shift in shadows can warrant an adjustment and reshoot. Narayanan, who worked with Zhang on a previous project, says that it was a “no-brainer” when Zhang asked him to reprise his role for [Shelf Life].

While Narayanan and other crew members chat on the couches as they await directions for the day’s shoot, Communication third-years Mia Mylvaganam and Sascha Deng set up a camera. As the film’s directors of photography, they’re preparing to execute the first shot of the day: a dolly shot.

The camera is fixated on a Dana Dolly, a device that allows it to slide horizontally to smoothly capture a wide view of an entire scene. Zhang looks at a monitor displaying the current frame, instructing Mylvaganam and Deng to shift the camera up or down to match the level of their shots from the previous days. Once they are satisfied, Mylvaganam slowly pulls the camera across the Dana Dolly, panning in and out of the dining room scene.

Mia Mylvaganam adjusts the camera position on the set.

Shelf Life’s crew members look on as the directors of photography shoot a frame.

Sascha Deng, Mia Mylvaganam and Erin Zhang analyze one of Shelf Life’s frames.

Mylvaganam and Deng have worked with Zhang since fall 2021, using [Shelf Life’s] script to devise a shot list of all of the camera movements and framing. Neither has prior experience with stop-motion films.

“It’s this new medium for almost everyone on set,” Mylvaganam says. “It’s so cool to see all of us coming together to learn this new skill and create something really impressive with it.”

After the dolly shot is complete, Mylvaganam and Deng reposition the camera and lock it into place. Zhang then begins instructions for the stop motion portion of filming.

“We’re going to do maybe 36 frames without food so all three [puppets] are just kind of moving,” Zhang says. “And then at 36, we’ll start to go into Girl One’s food.”

“To walk into this little space that’s completely artificial but feels so real and you have control over every single thing, that’s what is really exciting about stop motion. If I didn’t like that one piece, I can change the color. I can cut it up. I can destroy it.”

- Erin Zhang, Communication fourth-year

Two members of Shelf Life’s art crew crouch carefully between the set and the Dana Dolly. Using tweezers, they adjust the eyebrows and eyes of one puppet. For another, they move its feet slightly to initiate a kick. The third they leave untouched. After adjustments are made, they position themselves out of frame.

“Take,” Zhang says.

Deng hits a button on a controller, and the camera snaps a picture. The crew comes back into frame as Zhang gives instructions for the next shot. They reference monitors on each side of the set. Both are equipped with onion skin, an animating technique that overlays the current scene with the previous photo taken, so crew members can see the effect of their adjustments.

“It almost seems like when you’re animating, nothing’s happening because the moves are so little,” says Communication third-year and art crew member Sawyer Sadd. “You can feel like you’re [not] moving the doll at all but then look at the monitor and see that it’s moving so much.”

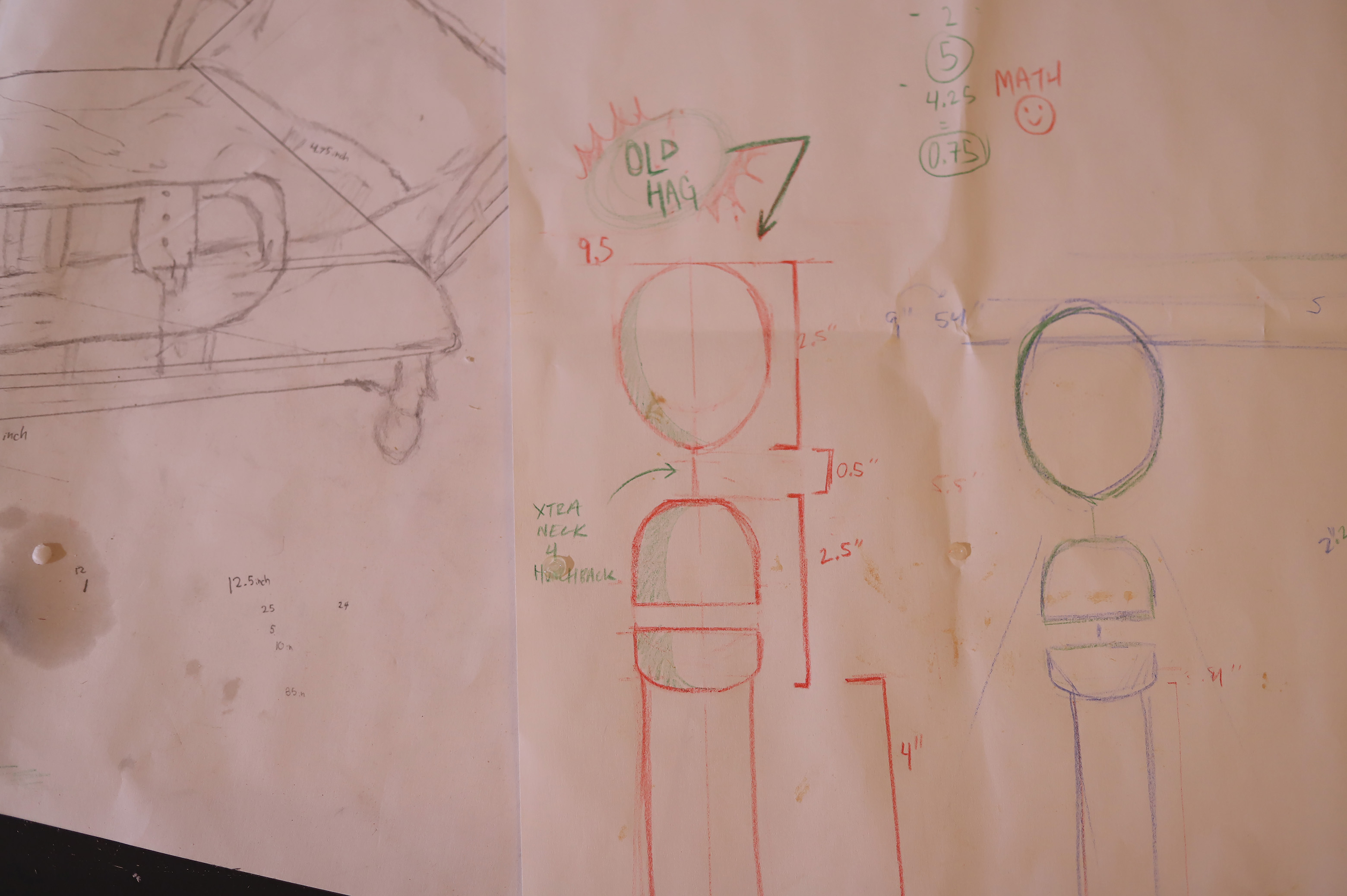

In addition to animating, Sadd and the rest of the art crew have worked in the basement since October 2021 to design [Shelf Life’s] puppets and set. Sadd’s first job was creating the initial sketches of each puppet and making sure all of the proportions were correct. While Sadd’s primary interests lie in animation and digital media, he says that those traditional types of animating tend to be more isolating.

“This process is super collaborative, especially in being an art crew,” he says. “Even when it comes down to the animation, you’re literally taking [it] frame by frame, so you’re all together in the same space. And I really liked that social aspect of it because I still get to exercise those creative bits of me but also get to be social.”

A plate of food ready to be ‘consumed’ by one of Shelf Life’s characters.

A close-up on one of the characters in Zhang’s stop-motion film, Shelf Life.

The design plans and dimensions for Shelf Life’s characters.

While the set and puppets are all created by the art crew, the miniature food sculptures — ranging from a tiny cup of ramen to a McDonald’s Southwest Salad — are all the work of Communication fourth-year Hannah So, the film’s editor. So was tasked with designing the miniature clay replicas because of her background in sculpting, having opened an Etsy shop for her creations.

“It’s always just been a creative, sort of therapeutic little outlet for me ever since high school,” So says. “I find when I’m focusing more on the little details of a sculpture, I’m worrying less about the bigger details of life.”

Now that shooting for [Shelf Life] has wrapped up, So sifts through footage, taking notes and preparing to edit. She says that she looks for takes where the characters’ facial expressions reflect the script, as well as ones that are technically sound.

“It’s always just been a creative, sort of therapeutic little outlet for me ever since high school. I find when I’m focusing more on the little details of a sculpture, I’m worrying less about the bigger details of life.”

- Hannah So, Communication fourth-year

For takes with minor flaws such as a camera wobble or a lighting shift, So must find ways to effectively conceal the technical blunders. She says that some options include incorporating a moment of stillness by freezing on a frame or, if the script allows, momentarily cutting to a different scene.

“Since stop motion is so laborious, there are only like three or four takes per shot,” So says. “[It] is a blessing and a curse.”

[Shelf Life] premieres on June 4 alongside the rest of Studio 22’s films. Zhang hopes that viewers will become more open to talking about the negative associations one might have with eating and consider how such a simple daily necessity can “have ripple effects in terms of emotions and memories and pain.”

“My attitude toward this wasn’t to do something depressing or about trauma. It was trying to think about all these complex emotions that arise when you think about disordered eating,” Zhang says. “[It’s] focusing on the complexity of food and positive and negative things that are associated.”