Today, Northwestern boasts a U.S. News & World Report Top 10 ranking and a 7% acceptance rate, cementing its prestigious academic reputation that attracts students from around the globe.

However, the University once educated just 10 students and struggled to gain traction as a legitimate institution of higher education after its founding in 1851. Its founders — Grant Goodrich, John Evans and Orrington Lunt — hoped the University would help preserve traditional Christian values through its partnership with the Methodist Church. These humble beginnings beg the question: How did Northwestern rise up the ranks and become the illustrious campus it is today?

Since the Midwest lacked the private preparatory feeder schools of the East Coast, Northwestern’s founders devised a plan to develop their own preparatory school. Following the school’s inception, Northwestern immediately moved to compete with prestigious colleges of the East, like Harvard and Yale.

“The establishment of a preparatory course of study allowed the faculty to set high standards for admission to the college. As early as 1855-56, entrance requirements at Northwestern were comparable to those at Harvard, Yale and Wesleyan,” Harold Williamson and Payson Wild say in their book Northwestern University: A History.

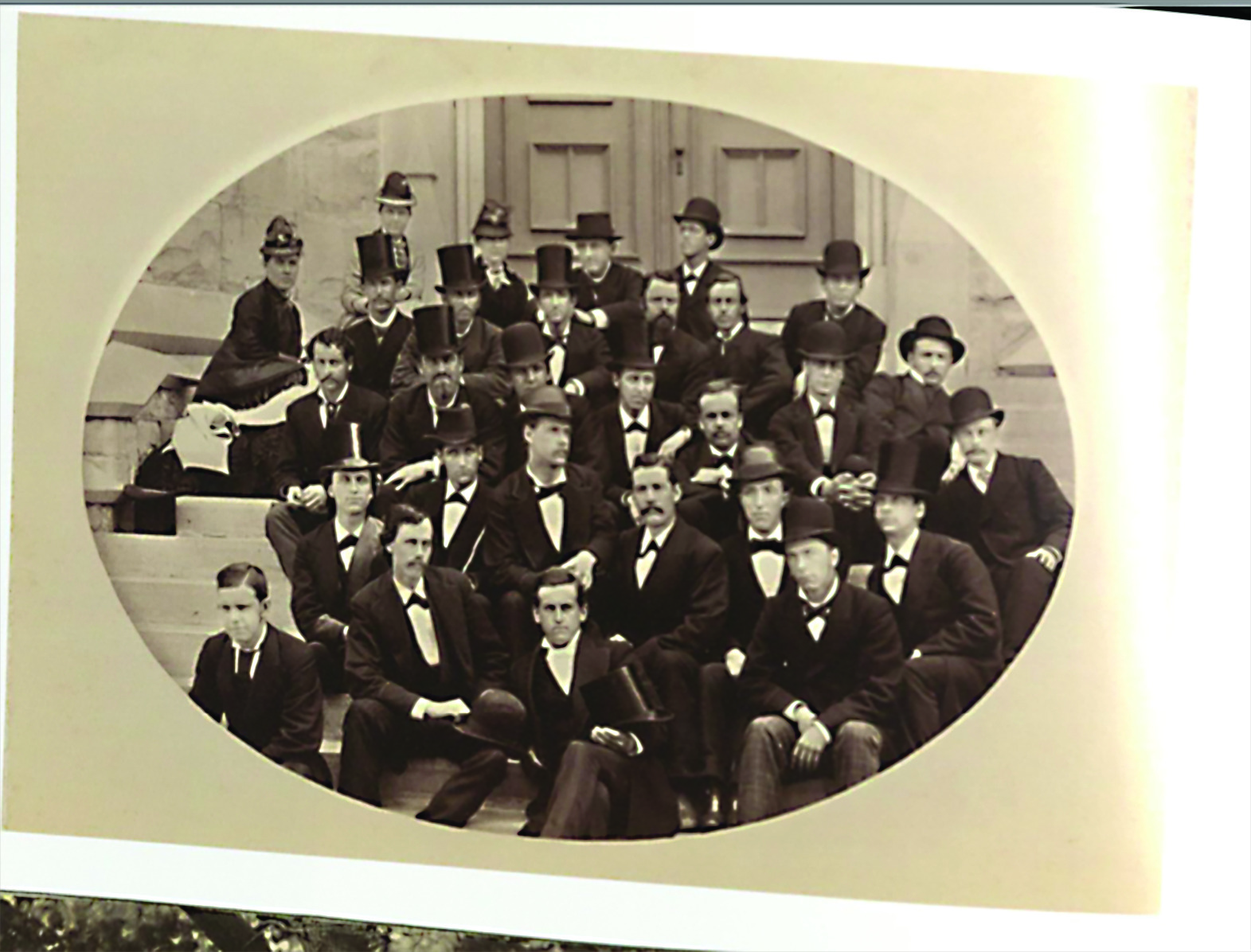

The Class of 1877 on the steps of University Hall. (Photo from University Archives)

Young men could attend the Northwestern preparatory school for up to three years before becoming full-time University students, helping to build the student population and get off the ground.

Fifteen years later, Northwestern began to consider admitting women to their University after pressures emerged from other exclusive schools that began to accept female students.

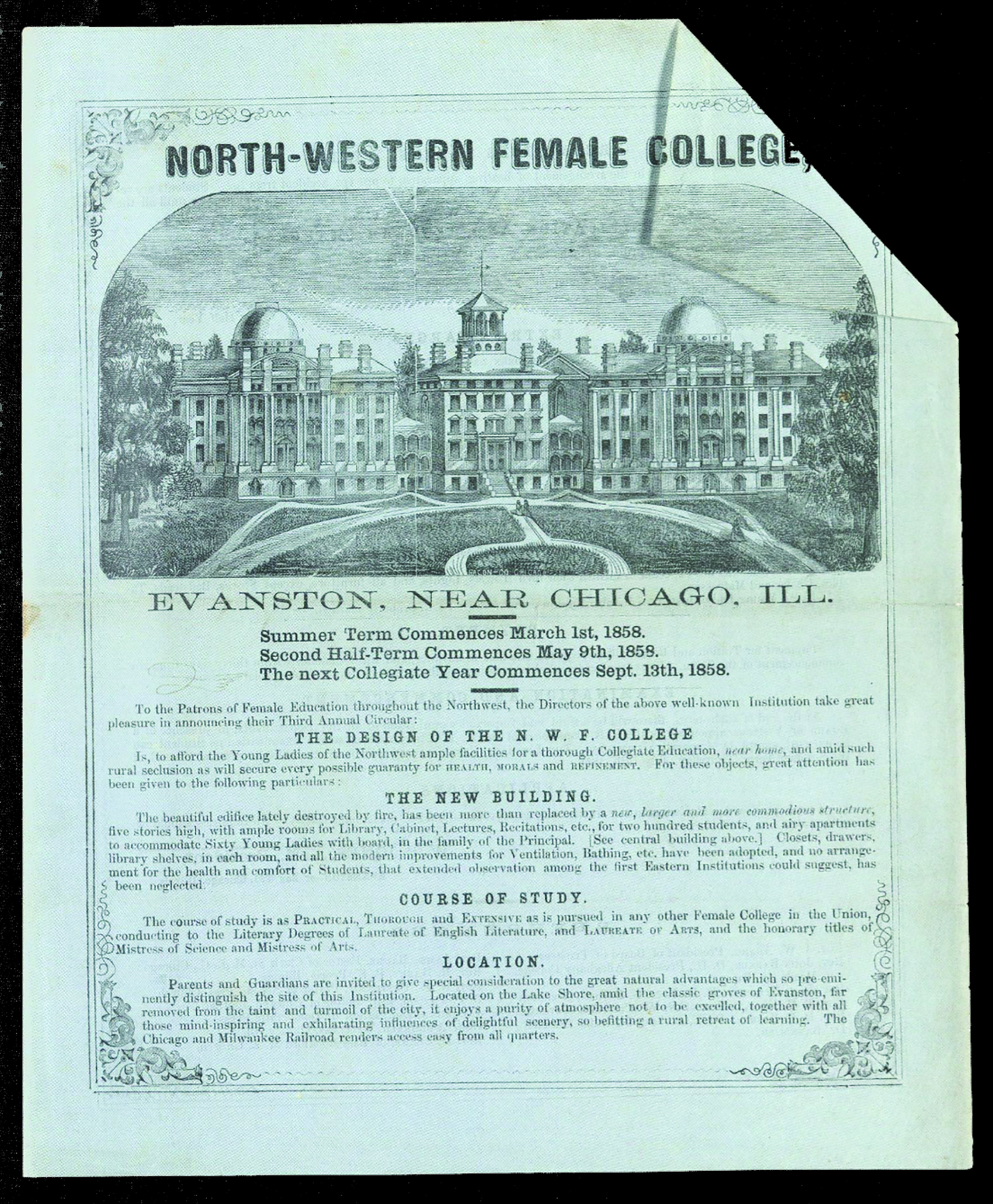

An imaginative sketch of the North-Western Female College in 1858. (Photo from University Archives)

Evanston was home to the North-Western Female College since 1855, the same year Northwestern welcomed its first class. The female college offered courses in classical studies at the modern-day middle and high school level, largely following the classes listed at Northwestern. Despite completing very similar coursework, the female college graduates were awarded only a laureate (essentially, recognition for their studies), as opposed to a bachelor’s degree.

While the North-Western Female College and Northwestern University coexisted, they had little interaction until 1870, when it was first proposed that the two institutions merge.

However, the University did not want to admit women students because they believed women required “special care” to retain societal morals while away from their families. As such, the two schools agreed to unite as one academic institution but retain separate spheres for living. The arrangement allowed women to access Northwestern libraries, classes and museums and even permitted them to study alongside their male peers in some cases. Despite this, female students continued to live in a female-only building with matrons to supervise and ensure nothing risqué occurred.

In 1871, North-Western Female College became Evanston College for Ladies. Its 1873-74 catalog proclaimed its goal to “provide a Home for Young Women where morals, health and manners can be constantly under the special care of women.”

Because of its careful supervision, the Evanston College for Ladies “attracted more women to Northwestern than to other universities in the region,” according to then Northwestern President Erastus Haven, as quoted in Williamson and Wild’s book.

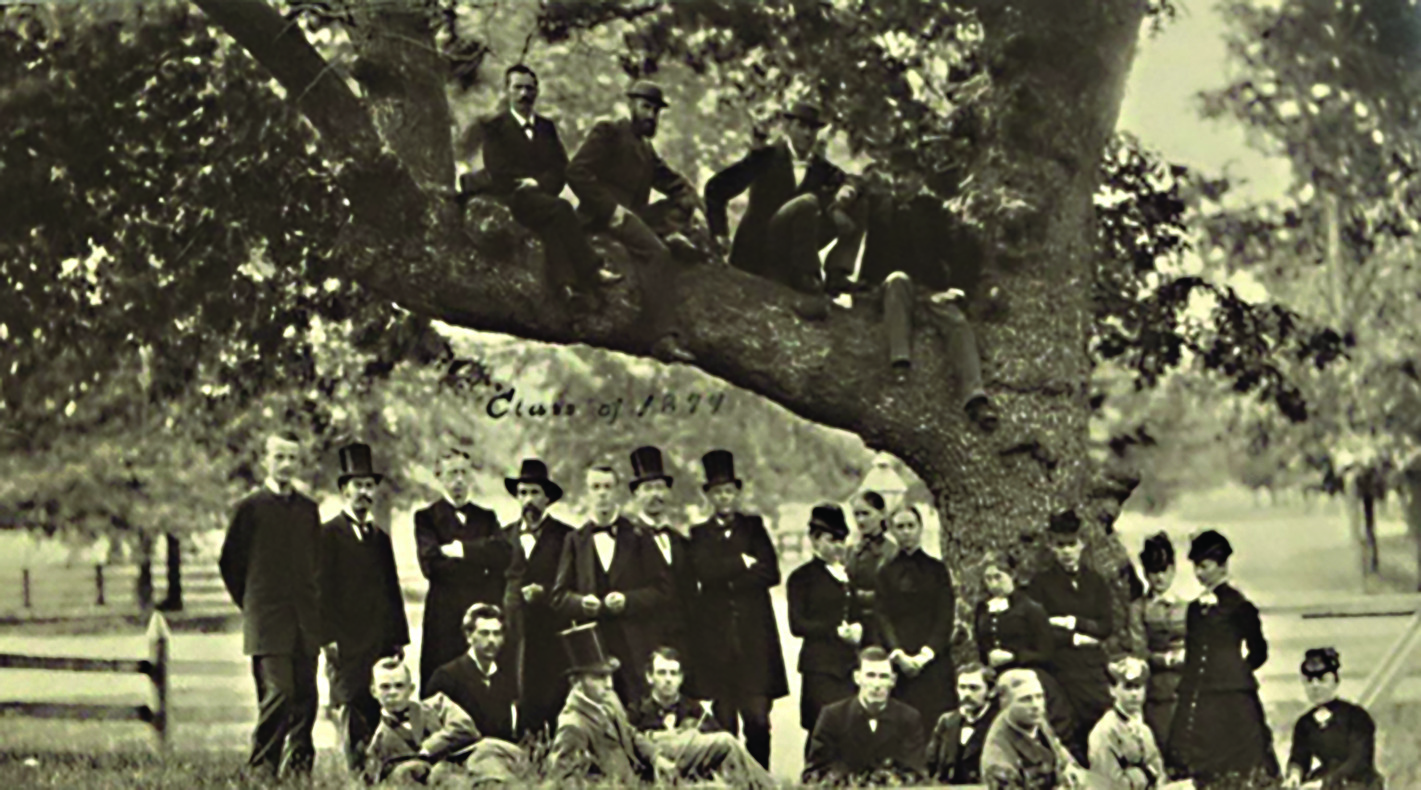

The Northwestern University Class of 1879. (Photo from University Archives)

In 1873, the Evanston College for Ladies was fully absorbed by the University and became the Women’s College of Northwestern. The University added a Dean of Women position, and Northwestern formally became a coeducational institution.

For many years, the University’s population remained largely white — although a few international students enrolled after attending protestant missionary schools in their countries of origin.

In 1903, Lawyer Taylor became Northwestern’s first Black graduate.

“Laying aside all humor and cheap wit, let us give nine rahs for a fellow who has fought his way thro’ college under more difficulties than any of us have ever encountered, who is the first of his race to receive a degree from Northwestern,” a classmate said at graduation, according to Jeffery Sterling and Lauren Lowery’s book Voices and Visions.

In 1902, the school formally segregated University housing, barring most Black students from living in dormitories. The Black men that did live in dorms usually did so only because they were on athletic teams and lived with the other players.

However, the segregation policy was enforced for all Black women, who were not allowed in dorms. Their only option was to find boarding in Evanston, which was extremely hard to come by. Many Black female students were forced to drop enrollment due to housing difficulties, like one who tried to live in Chapin Hall but was removed after white students complained.

College Cottage at Orrington and Clark housed women students from 1872 to 1935. (Photo from University Archives)

“At the conclusion of the school year last spring, a dozen or more girls at Chapin Hall informed the matron that they would not return to the school this year if colored coeds were admitted again,” reported the Chicago Tribune on Sept. 16, 1902.

The first desegregated dorm opened in 1947, largely influenced by the integrated military units of World War II. The International House, located at 1827 Orrington Ave., was open to Black women and international students, neither of whom were allowed in the other dorms.

Around the same time Black students were beginning to be admitted, the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) came into being. The SAT allowed universities to judge candidates on a supposedly objective level.

With the SAT, “the centerpiece of admission to elite higher education became an elusive concept: the applicant’s ‘character,’” says now Vice President of Inside Sales at Mercer Advisors Andrew Thompson in his undergraduate thesis on Northwestern admissions. As the standardized test became more popular and students learned to study for it, the University embraced additional measures of applicant differentiation. While some qualities like community service and extracurricular accomplishments were conventionally accepted, others were more sinister.

In the 1960s, the Anti-Defamation League submitted a report that outlined evidence of a Jewish admissions quota to the Northwestern administration. While the University removed the religious identification question on applications in 1957, the admissions team utilized other Jewish indicators — like living in certain areas — to block Jewish students’ acceptance. While the University’s investigation of the complaints only acknowledged “incompetence” and “inefficiency,” not overt anti-Semitism, Northwestern formed two new committees to oversee the admissions team.

The committees not only succeeded in decreasing anti-Semitism in the admissions process but also decreased racism in considering applications.

According to Thompson, 13% of Northwestern undergraduates self-identified as Jewish by 1964. Similarly, in 1966, a committee recruiting effort doubled the Black student population on campus.

The Black students demanded several changes to Northwestern policy, including a gradual increase of Black student admissions to make up 12% of incoming classes, the creation of a Black student committee to advise the admissions office and reserving separate living spaces for Black students. The latter two requests were granted, but the first was denied.

While admissions of Black students increased, racism and segregation still plagued the Black student experience. Tensions mounted and Black students protested by taking over the Bursar’s Office in 1968, an event still discussed today at the University.

The University also denied the demands to have Black students approve all appointments to the Human Relations Committee and to allow Black student representatives shared power with the Office of Admission when considering Black applicants.

It is difficult to assess the success of the new initiatives as few records exist prior to 1960 on admissions statistics and student demographics. However, post-1960, the administration began to retain detailed reports of admitted students. Post-1980, the first records of racial and geographic demographics of students are available.

In 1960, records show Northwestern received a total of 5,387 applications across first-year and transfer students, admitted 3,120 students and enrolled 2,021. Admitted students had an average class rank in the 87th percentile and averaged an SAT math score of 578 out of 800. Even as Northwestern grew in popularity, some administrators recognized the continued lack of diversity and accessibility in the incoming classes. The University offered almost no financial aid in securing residential accommodations, presenting a large barrier to attendance for those who were low-income yet forced to find off-campus housing.

In a Daily Northwestern article published on Jan. 12, 1965, then Dean of Students Roland Hinz insisted Northwestern needed greater diversity.

“There aren’t enough minority groups here, and there should be even more students from the East,” Hinz said in the article.

Hinz suggested that more students receive scholarships and that the University have a wider cross-section of society.

"It is the entire world we want to reach, influence and contribute to with our vitality and creativity."

Henry Bienen, Former University President

Following Hinz’s recommendations, Northwestern rolled out a new financial aid program totaling two million dollars.

“We were determined to change the University from being a regional institution to one of national and international distinction,” Clarence Ver Steeg, the Faculty Planning Committee lead member, said in 1968.

The new financial aid program helped Northwestern attract a more diverse student body from all over the world. By 1997 Northwestern received a total of 16,674 applications, admitted 4,909 and enrolled 1,891. Average class rank jumped to the 94th percentile, and enrolled students averaged an SAT math score of 694 out of 800.

In 37 years, Northwestern moved from a 57.9% acceptance rate to 29.4% from 1960-1997, contributing to its selective reputation and ever-increasing academic excellence.

But more than selectivity, Northwestern became a University open to young adults from every background. Each step in the University’s history has brought Northwestern closer to former University President Henry Bienen’s vision in his 2000 State of the University address:

“As we reflect upon Northwestern’s remarkable heritage, we now enter the 21st century renewed in our purpose of making the University an institution of the highest order of excellence, not just for the Northwest Territory, but for the entire world. It is the entire world we want to reach, influence and contribute to with our vitality and creativity.”

Today, the University’s admissions committee engenders heartache for many and joys for few. While progress in the diversity and equity of admissions is undeniable, archival research demonstrates just how far the institution has come.