The Bahá’í (Ba-HIGH) House of Worship towers over Chicago’s North Shore, drawing hundreds of thousands of visitors a year. Since March 2020, that number has dropped to zero.

The temple closed its doors in March 2020 but continued daily virtual programming. About 40 people attend each Zoom meeting, a figure that pales in comparison to the nearly 200,000 Bahá’ís in the U.S., said House of Worship Welcome Center Coordinator Ellen Price. They instead engage in local spiritual assemblies and have turned worship services called feasts into a virtual call, according to Wilmette Institute Director Robert Stockman.

“Zoom, in some ways, has been a benefit for smaller Bahá’í communities,” said Stockman, who gathers virtually with Bahá’ís in South Bend, Indiana. “We probably have 50% more people coming to feast because of Zoom because people don't have to leave the house.”

Closing North America’s only temple due to health regulations had a minimal effect on Bahá’ís located far from Wilmette, both in terms of community interaction and the financial health of the faith. The National Spiritual Assembly, the national governing body for Bahá’ís in the U.S., is ahead of previous years to meet its multi-million dollar goals for donations, according to Price.

“We don’t have a congregation that belongs to the temple, so it’s not like people come to the temple every Sunday and then contribute,” Price said. “We don’t get our money that way. The money comes from the National Bahá’í fund.”

The National Spiritual Assembly’s 2021 annual report notes over $42 million in contributions in fiscal year 2020, and over $37 million in contributions two months before the end of the current fiscal year. These voluntary gifts can only come from Bahá’ís and go toward upkeep of Wilmette’s House of Worship, three Bahá’í schools and the educational programs they offer.

Education and teaching activities are the National Spiritual Assembly’s highest expense, at over $16 million in fiscal year 2020, according to the annual report. Junior youth groups, children’s classes, devotions and study circles have all moved online during the pandemic, and Stockman noted an increase in enrollment and engagement in educational programs.

“It's been very good for isolated people and for people who want to study something together, and they can't get enough people within driving distance to do the study,” Stockman said.

Many Bahá’ís worship without a temple or meeting space, even before the pandemic. Individual and communal prayer can happen almost anywhere, according to Bahá’í Encyclopedia Project Coordinating Editor Gayle Morrison.

“I think the consciousness of the Bahá’í is that we don't need a church, we don't need a building,” Morrison said. “We don't need that to have that sacred space.”

In addition to the national fund, Bahá’ís must give to the House of Justice, the faith’s international governing body. Similar to a tithe, the Huqúqu'lláh is a spiritual obligation that states that Bahá’ís should make a payment of 19% of any excess wealth each year for development and operation of the faith. This fund is largely supported by U.S. Bahá’ís and makes the construction of temples around the world possible.

“You don't want to spend billions of dollars on lavish buildings with gold doorknobs and all this other stuff as a glorification of money,” Price said. “You want to have a respect and honor of God and to have places where people can go and have their heart lifted.”

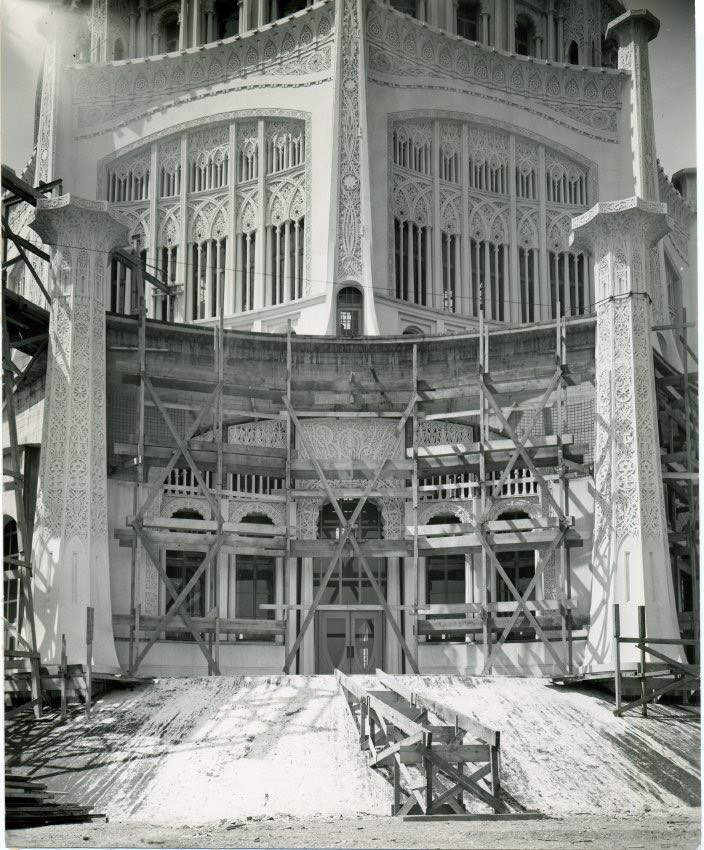

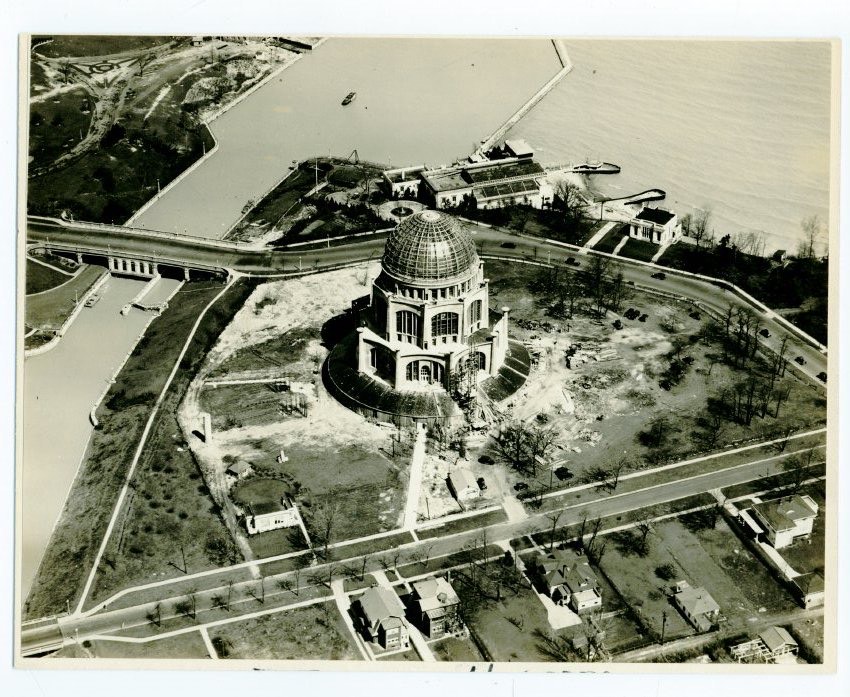

The Bahá’í faith began in the Middle East in the 19th century and emphasizes world peace and the unity of all people. An earthquake destroyed the first House of Worship in present day Turkmenistan, so the Wilmette temple is the oldest in the world. Symbols of different religions on the structure represent the Bahá’í belief in the unity of religion — the teachings of major religions are all derived from the same God.

Living near the House of Worship was a rare privilege for Morrison. Although she now practices her faith elsewhere, she said Chicago is important to Bahá’ís. For example, Morrison added, delegates at the national convention meet annually in the Chicago area to elect members to the National Assembly.

Chicago became the birthplace of the Bahá’í community in the U.S. after the Parliament of the World’s Religions in 1893, according to Price. Held alongside the World’s Fair, the interfaith dialogues increased interest for the Bahá’í faith after a Christian missionary read a report quoting its founder Baha'u'llah: “The earth is but one country and mankind its citizens.”

Bahá'u'lláh’s son, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, sent over a Bahá’í teacher from the Holy Land in Palestine. Chicago insurance salesman Thornton Chase became the first convert in the U.S., and the first few hundred Bahá’ís in the country were all from the city, Price said.

“The Bahá’í faith [in the U.S.] began here in Chicago,” Price said. “That's part of why it's kind of natural the temple grew out of that first experience here.”

Women of the faith wanted a lakefront temple while men wanted proximity to the city, and ʻAbdu'l-Bahá reinforced the Bahá’í principle of gender equality when he sided with the women, Price said. The women rode horse-drawn carriages over dirt roads to pick the grassy spot on the frontier and purchased it in 1908.

“The history of Wilmette and history of the temple aren't necessarily intricately intertwined, but it's very lucky that the temple ended up in Wilmette,” Wilmette Historical Museum Curator Rachel Ramirez said.

Public transportation didn’t reach Wilmette when Chicago Bahá’ís chose it. The elevated train stopped at Central Street in Evanston, not extending to Linden Avenue in Wilmette until 1912.

“They had to walk that last almost mile to get to the site,” Stockman said. “But it was just too expensive to buy land closer in.”

Fundraising continued throughout construction until the temple’s 1953 completion and dedication. The space looks forward to reopening its doors for worship. Still, with most U.S. Bahá’ís located far from the Mother Temple, many adherents want to take virtual aspects of the pandemic into the future.

“A lot of people have said, once we open up again, that they're hoping that we'll still be able to have a virtual aspect to it,” Price said.

*Article thumbnail by Margaret Fleming / North by Northwestern