Veronica Reyes is an 11-year veteran of Northwestern’s dining and service worker team. She’s a Compass employee working as a cashier at the Foster-Walker Complex dining hall, and she said she loves her job.

“That’s why I have not left my job,” she said. But with more than a decade at the University and two kids at home, Reyes only makes $14.05 per hour. Now, she’s organizing and participating in her potential first-ever strike.

On Sept. 22, Compass Group workers at Northwestern, which make up the University’s dining and service employees, passed a measure with 95% support to authorize a strike against the company. This tipping point came after two years of negotiations involving disputes over pay and benefits.

According to UNITE HERE Local 1, the union that represents Northwestern Compass workers, 58% of Northwestern Compass workers can’t afford to pay their bills. Another 53% cannot afford healthy food for their families, 43% went to a food pantry this year, and 74% have $1,000 or less in savings. Many workers make less than $15 per hour. Black women make an average of $14.96 per hour in comparison to their male counterparts, who earn $16.14 per hour.

“I have two kids,” Reyes said. “It’s impossible for me to help them with so little money. It’s hard to pay rent. I live here in Evanston, and rent and mortgage are very expensive; $14.05 is nothing.”

Elizabeth Arrguin has worked at Allison Dining Hall for 20 years. “I need more money because everything is up,” Arrguin said, talking about inflation while her wage remains stagnant. “That’s the reason I’m here.”

Much of the two-year long negotiation process was dedicated to raising the wages of workers like Arrguin. But it did little to resolve one of the workers’ main demands of a $19.88 per hour wage. In early September, Compass came to the union with their final offer. To most workers, their offer was unacceptable.

“It didn’t include a living wage, guaranteed health insurance,” said Neva Legallet, member of the Students Organizing for Labor Rights group on campus, which works closely to support dining and service workers. “So that’s when the conversation about escalation began.”

SOLR was originally founded in 2018, the same year that Compass began its partnership with Northwestern. SOLR has been organizing alongside Compass workers at Northwestern ever since. They have created petitions for students to sign to support workers and a mutual aid fund that anyone can donate to that has raised more than $100,000. Legallet said they also do more hands-on work, like donation drives that have collected clothing, PPE, toilet paper, food, and groceries.

The group’s work also extends to direct actions. “There was an incident last quarter when one worker tested positive [for COVID-19], and their co-workers were not notified until very late,” Legallet said. “We assisted some of those workers in demanding more accountability from their managers and communicating with workers about positive cases.”

SOLR focuses on amplifying information to raise awareness and make “workers feel more seen and heard,” Legallet said. She got involved when she saw a SOLR Instagram post about how many service workers had been laid off during the pandemic and weren’t getting their wages due to shutdowns that closed many dining locations. A Chicago Tribune article reported that Compass laid off around 40% of their staff this July.

“Since the pandemic, it’s the worst time I’ve lived as a worker,” said Graciela Escobedo, who has been at Northwestern for 14 years and is a cook in the Norris Center. “I feel like I’ve been left behind from the company.”

One of the biggest complaints among workers with Compass relates to health insurance. But earlier this year, during the pandemic, Compass changed how they determine which employees they will insure. With it, 74 workers lost health insurance, according to the Union.

Arrguin was one of these workers. “My husband needs my insurance,” she said. This fear is driving many to support the strike, even those who didn’t lose their insurance this year.

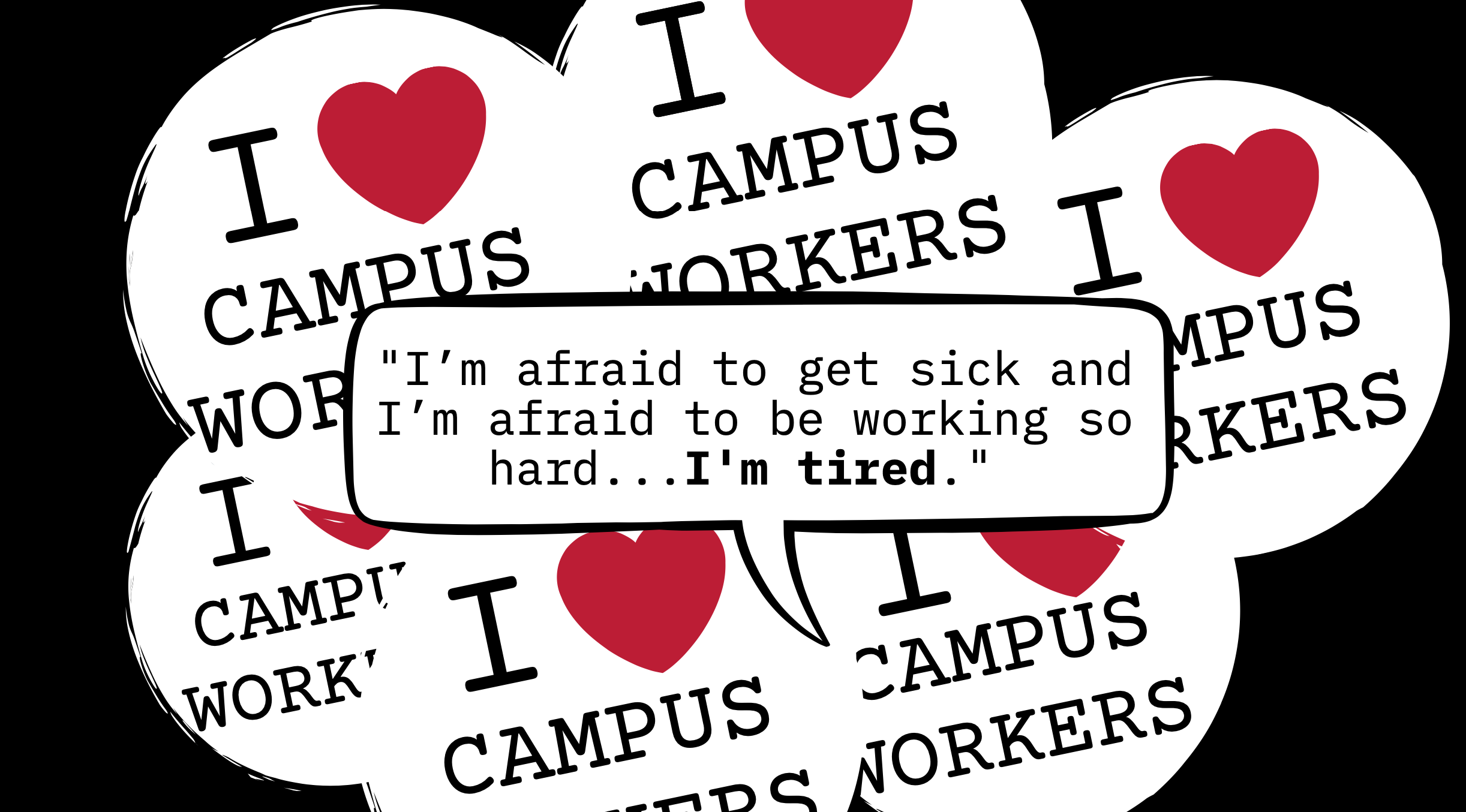

“I’m afraid to lose my insurance,” said Escobedo. “I’m afraid to get sick and I’m afraid to be working so hard and [not getting] the money I deserve. I’m tired.”

Escobedo said she is invested in the company, but doesn’t feel that is reciprocated to her. “Sometimes I work seven days a week. I support them every time they need me. And I don’t deserve to be left behind like this,” Escobedo said.

Based on the overwhelming vote to strike, she is not alone in that feeling of disconnect. “Everybody is ready [to strike] because they don’t want to lose the benefits,” said Arrguin.

In a statement to NBN, a Compass representative said, “Despite our last offer which would have provided an immediate $2 per hour raise to all associates, a one-time ratification bonus and over 20% raises over the life of the contract, the union declined our proposal without bringing it to a member vote.” However, the Compass representative believes that an agreement can be reached soon.

Though Northwestern does not directly employ dining workers and staff, the University has received criticism from students for not doing more to improve these workers’ conditions.

A spokesperson for Northwestern said, “The associates represented by the union are vital members of the Northwestern community, and Compass is a trusted partner to the University. We understand the importance of the ongoing contract negotiations …We hope for a swift and equitable resolution to these negotiations.”

But that doesn’t go far enough for some students. “The conditions that [Compass workers] work in is nothing a school that is higher education should tolerate,” Legallet said. “It’s entirely hypocritical [for the University] to not implement justice for its own workers.”

As negotiations continue, the workers have expressed some fear of what would happen if they need to strike.

“Of course I don’t want to go on strike. But I have to do it,” explained Escobedo. “I think most of us feel the very same way.”

Despite the daunting task, dining workers like Arrguin are resolved in their mission. “I am ready to fight and go to the street,” she said.

SOLR is planning on being there every step of the way. Most visibly last week, they ran the button-up campaign, which had buttons that read “I [heart] campus workers.” They were distributed everywhere, from the main campus to the Chicago branch. “The button campaign was very important for the workers’ morale,” Legallet said.

On Friday, SOLR rallied at the Kellogg Global Hub in support of the workers and against “the administration’s union-busting,” according to an Instagram post by the Northwestern Grad Workers union, who was also organizing the demonstration. “We want wider community support. It’s great to have students supporting, but it’s a community-wide issue,” Legallet said.

Working with the dining staff is the “most meaningful” activity Legallet said she has ever done on campus. Supporting these workers in this fight, she believes, is critical to give back for all they’ve done for students.

“No one’s experience on this campus would be the same without these workers,” Legallet said. “They’re some of the nicest and warmest people on this campus … I would just ask students to appreciate how much they do for us and how little recognition and appreciation they get.”

If the workers ultimately strike, it will be a first for all Northwestern Compass workers. For many, the strike feels like a means to getting something they believe they’ve earned.

“We just need a decent amount of money to live,” Reyes said. “I don’t think we’re asking for something we don’t deserve.”