Evanston uses marijuana legalization to address historic inequality.

In December, local dispensaries were preparing for the January 1 legalization of recreational marijuana. At the First Church of God, meanwhile, a crowd of over 600 Evanston residents gathered for a town hall to discuss reparations. In a historic new resolution, the city will allocate funds from a sales tax on recreational marijuana purchases to the Black community. Evanston activists saw legalization as an opportunity to take a step toward atoning for the decades of disproportionate marijuana arrests and redlining practices that targeted the Black community in the city.

At the meeting, city employees passed around notecards to solicit audience questions and comments about the policy. Some attendants left the cards blank, but not because they didn’t want to see a reparations resolution implemented. Actually, it was the opposite — they were worried that it wouldn’t work.

“I think there was a lot of hope in that room,” says Gabriella Johansson, a SESP third-year who staffs Evanston City Council’s reparations subcommittee. “But there’s also a lot of skepticism, because the city is the entity who has been hurting them for years.

It’s difficult to try to convince people that we’re going to try to do this right.”

Still, under the leadership of 5th Ward Alderman Robin Rue Simmons, the subcommittee continued to push forward. Simmons has been advocating for reparations since June, when the council passed a resolution committing to ending structural racism and achieving racial equity. According to Johansson, municipalities pass bills like this “all the time,” but they typically just acknowledge racial injustices without doing anything substantial to correct them. Simmons decided to do something concrete.

“This is innovative work,” Simmons says. “There has not been another municipality to look to as a reference or as a best practice.”

Illinois officially legalized recreational marijuana for adults over 21. Evanston’s reparations policy — which the council approved in an 8-to-1 vote in November — will implement a 3 percent sales tax on recreational marijuana that will contribute to the fund. The city is not allowed to begin collecting money until June 2020. After that, the fund will be financed over the course of 10 years and capped at $10 million. Distributions from the fund will likely not begin until 2021.

At a reparations subcommittee meeting three months after the town hall, Evanstonians sounded far less apprehensive of the resolution. Still, many residents have questions and concerns about how exactly the money will be spent. Bennett Johnson, who once collaborated with Martin Luther King Jr. and attends every subcommittee meeting, hopes the fund will become “self-sustaining.”

“You’re not trying to make people happy,” Johnson says. “You’re trying to make people function in society.”

This call for independence comes after decades of racial injustices against Black Evanstonians. In the 1850s, 125 African Americans were living in Evanston. By 1960, that number jumped to 9,126. According to the Founder of Shorefront Legacy Center Morris “Dino” Robinson, government initiatives, along with white, racist realtors, restricted African Americans’ place of living to underfunded areas. There, Black students were relegated to desperately underfunded schools.

"This policy is a first step in addressing racial violence and providing repair, but will not be sufficient in addressing everything." - Gabriella Johansson

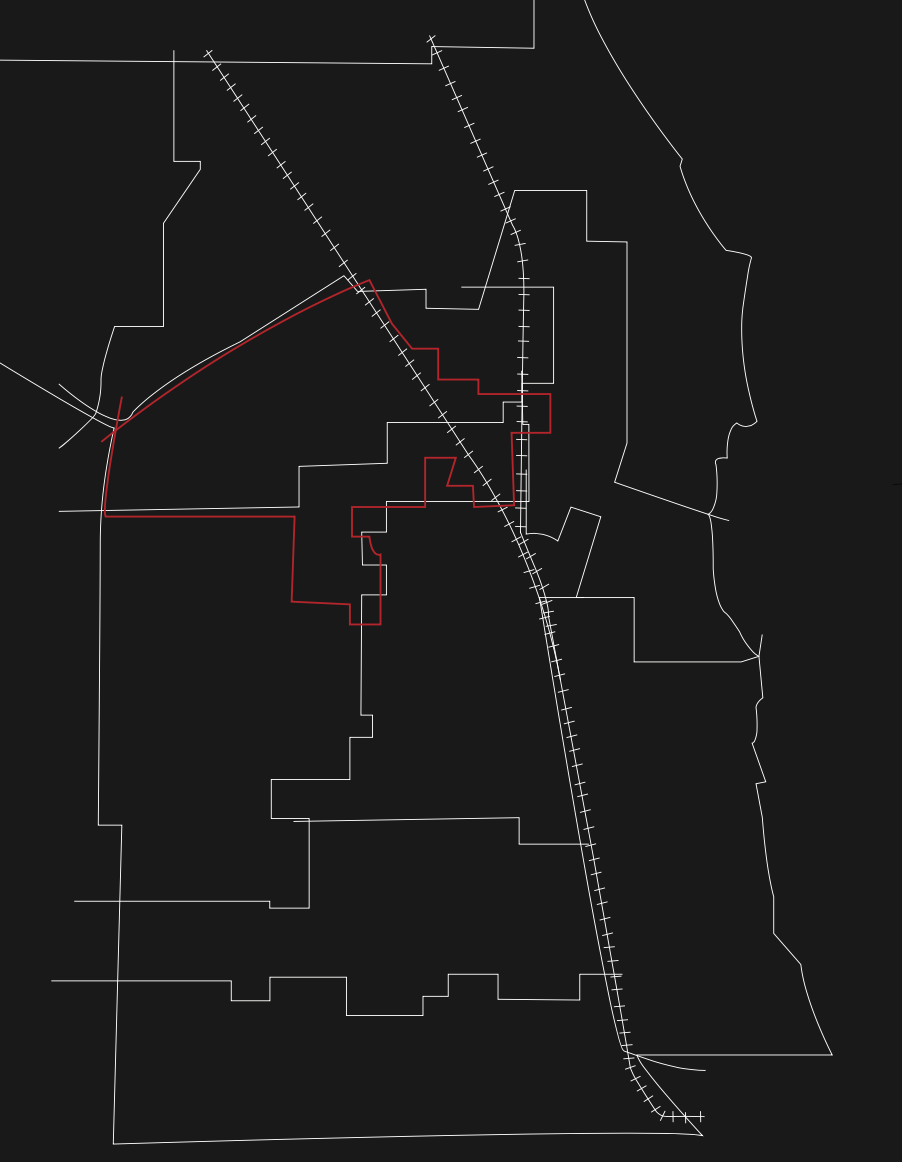

Redlining, the corrupt process of denying services (often financial) to residents of specific neighborhoods, usually based on race, has historically plagued Chicagoland housing. Racist practices in the real estate industry have existed for centuries, and this is an issue of national importance. In prominent cities all over the country, such as Detroit and Atlanta, similar redlining practices created neighborhoods with almost completely homogenous racial makeups. In the 1930s, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation developed what were essentially color-coded maps of the city, leading to institutional discrimination by real estate owners in certain areas.

Evanston has spurred national conversations in favor of reparations, but it remains the only city that has taken concrete steps toward addressing these historic inequalities. According to Northwestern political science Professor Reuel Rogers, the Evanston reparations resolution is not necessarily indicative of grand-scale national change.

“I think [Evanstonians] are more exposed to arguments that make the case for reparations and why it’s a suitable response to ongoing racial inequality than whites in other parts of the country might be,” Rogers says.

But Johansson is hopeful that Evanston will serve as a model for smaller municipalities as well as inspire tangible change at a state level.

Although recreational marijuana may be legal here and in several states around the nation, there are still local and federal laws in place that limit cannabis use. For Northwestern students, on-campus cannabis policies remain the same. Prior to students’ return from winter break, the University sent an email stating that it still prohibits the use and possession of marijuana on campus and at University events. And although students tend to be, at the very least, aware of recreational cannabis legalization in Illinois, Johansson says, they are often far less informed about the Evanston reparations resolution, a groundbreaking initiative in their own backyards.

But Evanstonians, especially those who live in Simmons’ district, are excited and moved by the proposition. They find lots of ways to keep conversations surrounding reparations moving forward, including the Facebook group “Evanston Reparations/ Solutions Only,” where community members are encouraged to post anything involving the fight for reparations, whether that be in Evanston or nationwide.

“I think that is something we have to work towards, but it is going to be a process that lasts for a long long time, evaluating and changing policy and transforming systems,” Johansson says. “This policy is a first step in addressing racial violence and providing repair, but will not be sufficient in addressing everything.”