“Alas, my child! That which saves the lives of others, proves thy destruction, even thy sire’s nobility; to thee thy father’s valiancy has proved no boon.”

--Euripides, Trojan Women

-399 B.C.E.-

The first man he had brought death to was his father. He brought it to him in a dirty golden goblet, stained purple with the earthy poison it often held. His mother had forfeited a not insubstantial amount of silver for the mixture — an Athenian family had no other recourse. It was their duty to support the will of the people, even if that will was bent to executing Lamprocles’ father for impiety. Thus was Lamprocles, the fittest of his family, reduced to Death’s delivery-boy.

Despite years of similar errands, he was not a very fast courier: he moved towards his destination in a cautious stabilizing tread. This was somewhat necessary, as he had to overcome the city’s most recent scars — scattered mounds of splintered stone and shredded wood. As he climbed over these remains of the Athenians’ once grand wall, he kept his goblet-hand locked and extended, so as not to spill the mixture.

Were he one year younger, he would have engineered such a spill rather than avoid it. He would have run in quiet tears to his mother and claimed an accident on the road or an incident at the herbalist’s store. She would have lightly scolded him, held him, then turned to her father for another loan to pay for the second dose. She would have gone herself the second time, to beg for a reduced price so that her children would not be hungry while they mourned. Shame and poverty for a day’s delay, it was an exchange he would have happily made.

But Lamprocles was thirteen years of age, and though not yet a man, he had begun to understand what it was that would make him so. Honor and duty obligated him to guard the goblet with his life. In daydreams, he had already laid down his life, drinking the hemlock himself as soon as he acquired it and thereby saving his father's life. But, in time, he recognized this childish plan for what it was: a lifeless body would do little to prevent his father’s execution. Now, his body’s only use was to safely deliver the contents he had been entrusted with. Virtue, however, did not obligate him to make the delivery quickly. Accordingly, he carefully steadied his leg prior to every footfall, without exception or haste.

It was late morning, the first assembly of the day had come to an end, and the marketplace was laced with sunlight and citizens. Lamprocles avoided the animated crowds, following the zig-zag of the southern sea breeze to the edge of the marketplace. The surrounding hills and looming citadel restrained the sun’s light, leaving the colonnades of the jail in shadowy relief and obscuring the entrance and its guard. Lamprocles approached the entrance, greeted the guard with a low nod, and walked towards the distinctive blue of his mother’s formal tunic.

Xanthippe’s head was erect as he approached. She cast a red-eyed glance at him as her embrace continued to muffle the sobs of Sophroniscos, Lamprocles' younger brother. Leaving the poison on the dais, Lamprocles moved to join his mother but did not sit down.

“Greetings mother. My task is complete — How are you?” he asked, trying to stand as straight and formal as he could.

“Tired,” she sighed. “Always tired. We’ve been waiting and your poor brother is inconsolable.” She stroked Sophroniscos’ matted hair. “He hasn’t stopped crying since yesterday.”

Lamprocles nodded. “I can stay here. Why don’t you go and try to find Father? His presence may calm Sophroniscos some.”

Xanthippe nodded to her oldest son and raised her perpetually bent figure, while Lamprocles took her place. Sophroniscos was only four years younger than Lamprocles, but still he had to look up to meet his brother’s face.

“She’ll find him, right?” asked Sophroniscos “He’s not... he wouldn’t be gone already...”

“Don’t worry, she will,” assured Lamprocles listening down the hall. He heard nothing.

“It’s not fair!” Sophroniscos was crying again. “How can they just take him away from us? Who will teach us our letters now? How will-?”

“Calm down. Being upset helps no one. They’re executing our father, that is enough." Lamprocles stopped, hearing voices down the hall. Even down a granite hallway he recognized these exasperated voices; in one way or another he was always listening for them. Sophroniscos stopped crying.

"Oh, what new foolishness is this?” asked a voice that sounded like their father. “Crito my friend, are you responsible for this? Do you think that by calling my family you will move my heart to cowardice? Surely..."

A woman’s voice, so loud it could only be his mother’s. “Crito called no one! I came to speak to an old goat, that would rather leave his family to starve than humble himself in court.”

“But, my dear, it would be a lie. My daemon commands me to seek truth, would I not be the ultimate hypocrite if I were to lie now? I was just explaining to Crito and young Phaedo the necessity of—”

“I don’t care anymore,” cut in Lamprocles’ mother. “No more arguments, no more philosophy. Will you at least come and speak with the children?”

“Of course, my dear, of course. I can spare some time for the boys. But please, be more respectful. Don't I deserve at least a little bit of your esteem? I am still your husband, and I am dying today, should that not count for something?”

There was no reply.

Lamprocles stood and admired the silence. It broke only when Sophroniscos saw their parents walking down the hall towards him. As quickly as it had quieted, the hall was ringing with clamor once again.

Lamprocles stayed apart, seated. He watched his mother, father, and brother exchange their last words and rehearsed what he would say. He had spent most of the night running the words over his lips again and again, until he could make his case through pure habit of muscle. Still, making the request directly to his father, it would be difficult.

Eventually Crito motioned to their father from the other room, and Xanthippe took Sophroniscos' hand as the family was disassembled. Sophroniscos complained loudly and fought the pull, but some stern words from their father soon convinced him to go. They exited the jail, Xanthippe downcast, her eyes on the child holding her hand, and Sophroniscos crying himself quiet beside her.

Finally, Lamprocles rose and, passing his mother, went to his father.

“Father, I have long considered what action would be most proper — most educating — at this important time. I think, while you are… or are about to…”

His father blinked at him as if he was a lost child.

“as you… farewell life,” Lamprocles recovered, “I think I would like to be there.”

“Your concern is appreciated my son, but the deathbed is no place for a child. Crying and grieving, it would be inappropriate.”

“Please father, I promise, I won’t cry. I’ve always listened to you. If you say it is a good thing to die, to be free of this life, then I know you are right. I just want to be there and see.”

His father shrugged. “I suppose there is no harm. I have Phaedo and a few other of the boys here for a final exchange, keep your reason about you and you can stay. Just, don’t interrupt my boy, you’re still a little too young for philosophy.”

Lamprocles nodded vigorously, then restrained himself to a solemn bow. His father had already turned away and Lamprocles quickly followed his sandaled footsteps.

Lamprocles made good on his word. Later, in the dim prison cell, warm and crowded with students, his father drank the poison in libation. Crito, older even than his father, sobbed for his childhood friend. Plato, too, usually remote, wept as all the grown men collapsed into tears.

Lamprocles minded his posture and leaned forward to hear his father’s words over the noise.

“What is this, you strange fellows?” cried his father. “It is mainly for this reason that I sent the woman away, to avoid such unseemliness. One should die in a good omened silence. Control yourselves!” Suddenly, his voice faded to a whisper and he reclined onto his bed. “Here it is; the numbness crawls to my chest. We owe a favor to the gods, Crito.”

Lamprocles held his father's gaze, even as the hemlock turned veins white in front of him. Nothing, save the annoying and constant need to blink, could draw his attention away.

Eventually, men began to move around Lamprocles. There was talking, and the vagaries of hushed discussion. People left. People came in. Plato made loud declarations that were met with subdued cheers. Lamprocles attention could not waver.

He thought about a great deal in that room. The points he chose to emphasize, the special knowledge he told friends that he had discovered in that room, changed with time. What did not change was the last image of his father: blank white eyes, stiff shoulders, lips stained by the earthy poison Lamprocles had brought. His father’s dead body was an illustrated proof, a manifest argument, of how little life was worth.

That memory always brought him certainty. It reminded him that death for the sake of virtue could be acceptable, even beautiful. When other Athenians would call him traitor, when his sword-hand would waver, when he would bring so many more men and women to death – his father’s image gave him the conviction to continue. Lamprocles lived ever hoping that, had Socrates lived, his father would have been proud of him.

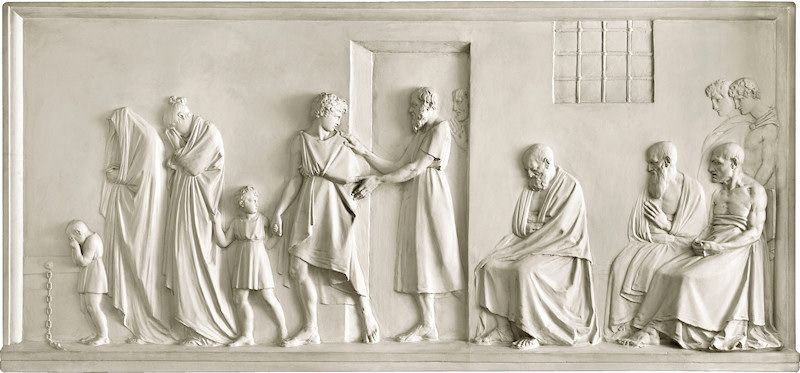

Article Thumbnail: Fondazione Cariplo / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)