Fiona McCarthy chose to move to Evanston’s Seventh Ward because of its character, walkability and sense of community. As the parent of two young children, she appreciates the area for its parks and friendly neighbors, as well as access to the Central Street business corridor. But from her doorstep, she can see the subject of a new debate that’s reigniting decades-old discourse about the relationship between Evanston and Northwestern University – Ryan Field.

In September 2021, Northwestern announced plans to renovate the 97-year-old stadium, located on Central Street in the heart of Evanston’s northeastern-most ward. For the estimated $800 million venture to be financially viable, the University says it will need to host public-facing concerts and needs to change Evanston’s zoning laws to do so. This January, Northwestern submitted a zoning ordinance text amendment application that would allow the University to host up to 10 concerts each year, up to the 35,000-person capacity of the new Ryan Field.

“Honestly, if they approved that, and we were looking to buy now, we wouldn't move east of Green Bay Road,” McCarthy said. “We'd maybe live somewhere else in Evanston, but we wouldn't live where we do.”

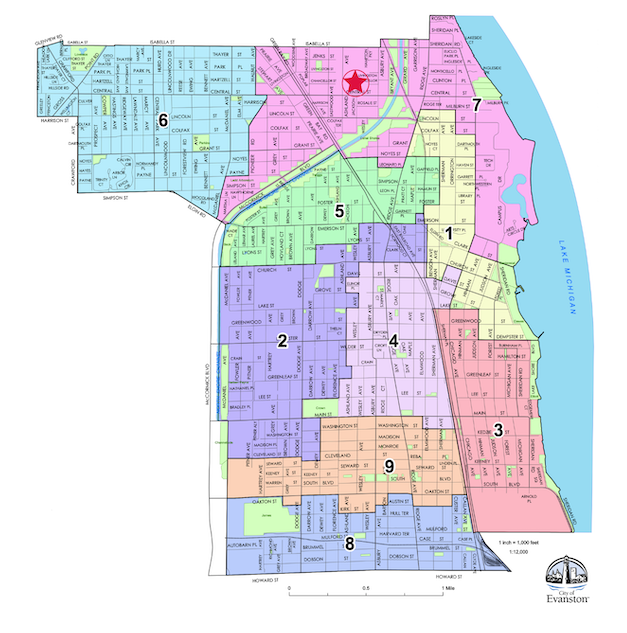

Red star is where Ryan Field is located, between Ashland Avenue to the west and Asbury Avenue to the east. The stadium lies along the Central Street Business Corridor to the south. The University is advertising that the new stadium will be more accessible than the current structure, and it will have a Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) gold certification. Map courtesy of the City of Evanston, graphic by Olivia Lloyd/North by Northwestern

Concerns about construction and concerts have resurfaced deep-seated questions about whether the University is a responsible neighbor contributing its fair share to a City that it has been at odds with in the past.

“It's Northwestern's money, it's their property, if they're going to build it, they can build it, and there is economic benefit to the city just through the construction process,” McCarthy said. “I do think that I'm against changing the zoning. I think that's the critical piece.”

Some Seventh Ward residents like McCarthy have said they don’t oppose a new stadium, but they do oppose concerts. Yet Northwestern says one can’t happen without the other.

Re-zoning Evanston

Ryan Field and Welsh-Ryan Arena lie in Evanston’s U2 University Athletic Facilities District. The commercial, public-facing concerts Northwestern is suggesting are not permitted under the current zoning ordinance, which largely limits the area to Northwestern home games and other smaller events under 10,000 people.

“I think that for a lot of people, the stadium is just kind of the last straw for them,” said Lesley Williams, a Seventh Ward resident and the president of the Community Alliance for Better Government, a grassroots organization that supports racial equity and government transparency. “They feel for years that Northwestern has ignored the concerns of residents. And the arrogance of trying to build this project is just confirmation of what people have felt about that arrogance.”

Dave Davis, Northwestern’s Executive Director of Neighborhood and Community Relations, said the University has made a commitment that the project will be completely self-supporting within the Department of Athletics and Recreation, meaning it will not redirect resources from academics and research.

“And so to do that, it's important that we're able to bring in enough net revenues from larger events, such as concerts, so that it can be reinvested into the stadium to maintain it and then activate it for the broader community use,” Davis said.

Northwestern announced the project in Fall of 2021 after receiving a $480 million donation from the Patrick and Shirley Ryan Family. Their donation was part of the University’s “We Will” fundraising campaign, which raised more than $6.1 billion from 2014 to 2021. Approximately $270 million of the Ryan Family’s gift will go towards redeveloping the stadium, and the rest will be privately funded, according to Northwestern’s Athletics Department.

This is not the first time Northwestern has attempted to host commercial events in the U2 District. Going back to the 1970s, Northwestern and Evanston fought legal battles over the University’s attempts to host professional sporting events on its property.

Northwestern’s property tax-exempt status has also been the subject of discussion for decades. As a non-profit, the University doesn’t pay property taxes on any of its land, which made up about 10% of the property in Evanston as of 2017, according to a city study. The University pays other municipal, state and federal taxes, and the new Ryan Field would generate tax revenue for Evanston through local amusement, sales, liquor and parking taxes.

In 2002, Northwestern sued Evanston for creating a historic preservation district that the University said wrongfully included Northwestern properties. Northwestern claimed the City was motivated by “an illegitimate animus toward the University, animus stemming from frustration with Northwestern's property-tax exemption and attendant refusal to make voluntary contributions for the provision of City services,” according to the suit ruling.

Tensions around Northwestern’s property tax exemption have resulted in referendums, lawsuits and conversations that are coming up once again with the Ryan Field project, as residents question the fairness of Northwestern’s proposed concert ventures.

“I don’t understand how this new entertainment complex, essentially, is in keeping with Northwestern’s charter as a not-for-profit,” said Lynn Bednar, a Seventh Ward resident and Central Street business owner. “I think that's an abuse of their not-for-profit status.”

In 2019, Seventh Ward Councilmember Eleanor Revelle opposed an ordinance that would have temporarily re-zoned the U2 District for similar uses the University is seeking now. That ordinance passed, but it never came to fruition because of the pandemic. Now, with new councilmembers in office and a proposal to not only host larger events but rebuild the entire stadium, the situation is different.

Revelle said she has begun tallying backers versus dissenters based on feedback she has received from her constituents. As it stands, she has heard more opposition than support.

“Residents in the area bought their homes understanding that it was an athletic facility with football games and university educational uses, and so the idea that it might become a place where commercial entertainment events would take place, it's kind of like changing the rules on them after the fact,” Revelle said.

Evanston’s Economic Development Committee voted to hire an independent contractor to conduct its own economic impact study on behalf of the City, set to be completed by July 2023. Revelle and her councilmembers agreed this was a necessary step after Northwestern’s initial economic impact study by consulting firm Tripp Umbach drew skepticism from some city officials and the community.

One critic of the project at the city level is Sixth Ward Councilmember Thomas Suffredin. He spoke out against Northwestern’s proposal in a newsletter to his ward in early March, telling University officials to “go back to the drawing board – and come back when they’re serious.”

Davis said that all 10 of the proposed concerts might not be at Ryan Field, which will have a 35,000-person capacity, a reduction from its current 47,000-person capacity. Some of the concerts could take place at Welsh-Ryan Arena, which has a capacity of 7,000.

However, residents expressed concern that the University, in its zoning proposal, was seeking to host events of up to 10,000 people without putting a cap on the number of such events.

The University is currently revising its original amendment to tighten some of the language, specifically around the events of up to 10,000 people, according to Revelle and University spokesperson Jon Yates.

Coming Together

On a sunny day in February, the town hall in Fleetwood-Jourdain Community Center came to order.

A steady stream of Evanston residents flowed in. They signed in at a table up front and took their seats, then got up again to say hello to friends and neighbors, many discussing the topic that they had all gathered to hear more about that day.

Five Evanston community groups convened an open meeting to discuss issues stemming from the Ryan Field project, ranging from labor to equitable development to zoning concerns.

Lesley Williams, president of Community Alliance for Better Government, organized and moderated the February 19 town hall. The speakers included Emilie Lozier from Northwestern University Graduate Workers, David Ellis with the Fair Share Action Committee, Kevin Brown with the Community Alliance for Better Government, and David DeCarlo with Most Livable City Association. Central Street Neighbors Association was involved in organizing the event as well. Photo by Olivia Lloyd/North by Northwestern.

“Right now, we're at the precipice with Northwestern wanting this stadium development,” said David Ellis, former co-chair of the Fair Share Action Committee. “The Council has leverage, the citizens have leverage to be able to get something for what Northwestern wants. Typically they act unilaterally and we deal with it afterwards. But with [Ryan Field], now's the time where we can get the ability to negotiate.”

Part of Northwestern’s proposed plan involves spending a target 35% of the project’s subcontracting budget on women-owned and minority-owned businesses, with priority given to businesses and individuals in Evanston.

Northwestern Alumnus (WCAS '85) Kevin Brown is a board member of the Community Alliance for Better Government. At the town hall, he was skeptical about Northwestern’s claim that this project will benefit Evanston’s disenfranchised communities. In his years working with Northwestern, Brown said it’s typical for the University to “take the photograph, to tell the community that they are doing something positive to uplift the community, but not sustain the effort.”

Northwestern’s use of $800 million to rebuild the stadium has also drawn criticism from some community members.

“I was disappointed when this proposal came out for this billion-dollar entertainment complex,” Brown said, “given all of the challenges that we have in this community, particularly downtown, the homeless problem that we're seeing in the city along with the violence that's taking place for young people in this community.”

Northwestern says the Ryan Field project will be an economic engine for the community, creating nearly 3,000 jobs and generating $660 million for Evanston during the construction process. University officials haven’t shared how much it will profit from the venture.

But David DeCarlo, of Most Livable City and a Seventh Ward resident, believes a trickle down effect from taxes isn’t enough.

“If we band together, we can try to reach an agreement that is way more reasonable than this,” DeCarlo said.

In the end, the votes to approve the project rest with the City Council, which is composed of nine members who represent each of Evanston’s nine wards. For Williams, the purpose for galvanizing the community is to build a coalition of residents across Evanston that can push for their councilmembers to heed their concerns.

“I think initially we're appealing to the community, because the City Council, although they don't always remember that, do in fact work for the community and for the people in their wards,” Williams said. “We hope this will stir up the community to really pressure the City Council to meet the community's demands and not just Northwestern's demands.”

If Northwestern will be holding concerts, residents are seeking concessions, potentially including a payment in lieu of taxes (PILOT) or a community benefits agreement. The latter is a contract between a developer and community members that would hold the developer accountable for delivering certain benefits in exchange for community support. These ideas came up several times at the town hall meeting.

Davis said changeover in the last few years among University leadership and City officials have disrupted conversations about Northwestern's contributions to the city. The conversations have started up again now that President Michael Schill is in office, but for now, Davis said payments in lieu of taxes might not be the right idea.

“We have a mechanism of how we support and fund the city,” Davis said. “We're just not sure if PILOTs are the right approach, particularly right now, but we do and we have supported the city for a number of years and will continue to partner with the City of Evanston.”

Revelle said the University does contribute to the community in many ways, albeit not always in the form of “money in the bank.”

“I think the University is very averse to the term payment in lieu of taxes because the University's charter makes it clear that they don't have to pay property taxes,” Revelle said. “But probably, if we do end up with some kind of payment, I would think it would not be called a payment in lieu of taxes. Maybe ‘community benefit fund’ is probably a better term.”

Impact on the Seventh Ward

Although Revelle said her tally marks have counted more critics than supporters, some business owners and residents across Evanston have come out in favor of the project.

Pat Fowler, the owner of Bluestone restaurant on Central Street, as well as Firehouse Grill off Main Street, said he’s excited about the stadium, as he estimates that he doubles or triples normal sales on game days.

“From a business standpoint, it definitely helps draw more customers through the doors, which not only helps me, but our staff too,” Fowler said.

However, he’s sympathetic to other business owners around him that may not profit as much.

“Having said that, I can also hear where some people want some solutions to what they think are potential problems with the project,” he said. “And I think hopefully Northwestern is working to address those issues.”

Lynn Bednar, the owner of Walsh Natural Health on Central Street, doubts a new stadium and concerts will help her business, which primarily sells supplements, essential oils and natural body care products.

“All the clothing businesses, the floral shops, perhaps the salons, none of these businesses are benefited by people walking by going to a concert,” she said.

Kandi Corbbins, the owner of iKandi Hair Studio, expressed similar worries for her business in an op-ed for Crain’s Chicago Business in March. Her shop is on Central Street, a block from Ryan Field. She estimated that she loses a third of her business during Northwestern football home games. Her reservations also lie in the way the University is promoting the benefits of the stadium.

“Northwestern’s slick public relations campaign claims the new Ryan Field will ‘build generational wealth for Black and Brown families.’ As the owner of one of Central Street’s few Black-owned businesses, I have my doubts” Corbbins wrote. “What I see, instead, is … powerful Evanstonians coalescing behind the plan and cynically using artificial promises of Black wealth as cover.”

A yard sign on Orrington Ave. in the First Ward. Most Livable City contributed to the design, printing and distribution of the signs. Photo by Coop Daley/North by Northwestern.

Emails obtained through records requests show that the dialogue among the city, community members and University officials is nuanced. Many who expressed support for the project are concerned about parking, the environmental impact of construction and the height of the stadium, while critics have said they see the benefit to Evanston’s hospitality industry and the draw for neighbors who enjoy live music.

Evidence of this debate is visible on Evanston’s street corners. In one neighborhood in north Evanston, one of Northwestern’s Rebuild Ryan Field yard signs was staked in the ground opposite another home with a yard sign saying, “We’ve had ENOUGH.” Groups saying they support or oppose the concerts have been popping up, from Most Livable City to Fans of Ryan Field.

“The negative always appears the loudest because they have more energy,” said Patrick Hughes Jr., a Seventh Ward resident and member of Fans of Ryan Field.“But the negative in Evanston is always organized … So there's a need for the positive to also organize.”

In affiliation with Most Livable City, however, Seventh Ward resident Aaron Cohen questioned the University’s proposal.

“In order to make the stadium viable, they have to change the zoning to allow for-profit events and yet still maintain its not-for-profit status,” Cohen said. “Well, I've been a homeowner and taxpayer in Evanston for 40 years. And I can assure you that our taxes have only gone in one direction.”

Given Northwestern’s $14.4 billion endowment as of 2022 and that its annual revenue surplus usually reaches upwards of $80 million, Cohen said he had a hard time understanding why the concerts were necessary.

“It's reaching the point where my wife and I are kind of keenly aware of it, as are many neighbors: We are subsidizing Northwestern, which has accrued tremendous wealth that other businesses would be taxed on, and it behaves as a business,” Cohen said.

For some Evanstonians, it boils down to changing long-held zoning laws so Northwestern can host its commercial ventures.

“I think we have to distinguish between the stadium and the entertainment complex. I don't think most of the opposition is against the stadium itself,” Williams said. “It's really turning the entire area into this year-long entertainment zone that's the issue, and the precedent that that sets.”

McCarthy said she enjoys going to Northwestern football games and tailgates. A new stadium that could host a community ice rink or a Christmas market is exciting, she said. But when it comes to rezoning the district, selling alcohol and hosting concerts, she’s concerned.

"Once that zoning changes, and once that precedent is set that these professional, large-scale events are happening, there is nothing stopping Northwestern from saying, 'Well, now we want 20, or we want one every weekend…'" McCarthy said. “You’re opening Pandora’s Box.”

*Thumbnail photo from Maren Kranking/North by Northwestern. Graphic by Olivia Lloyd/North by Northwestern