When Northwestern PhD candidate Adam Goldsmith concluded his third hour-long interview with long-time Evanston resident Bennett Johnson, he had gathered countless stories from Johnson's 70 years in the city. Recording Johnson's life made Goldsmith realize the necessity of preserving the memories of Evanston residents.

“It was a really cool experience to ask questions to open up the windows into the story of somebody else,” Goldsmith says.

Goldsmith was working on an oral history project launched in 2020 by Northwestern's Center for Civic Engagement (CCE). The project's initial goal was to combat isolation among older citizens during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to project manager Alexandra Gonzalez, a graduate assistant at CCE, the interviews were also intended to create meaningful, personal relationships between Evanston seniors and Northwestern students.

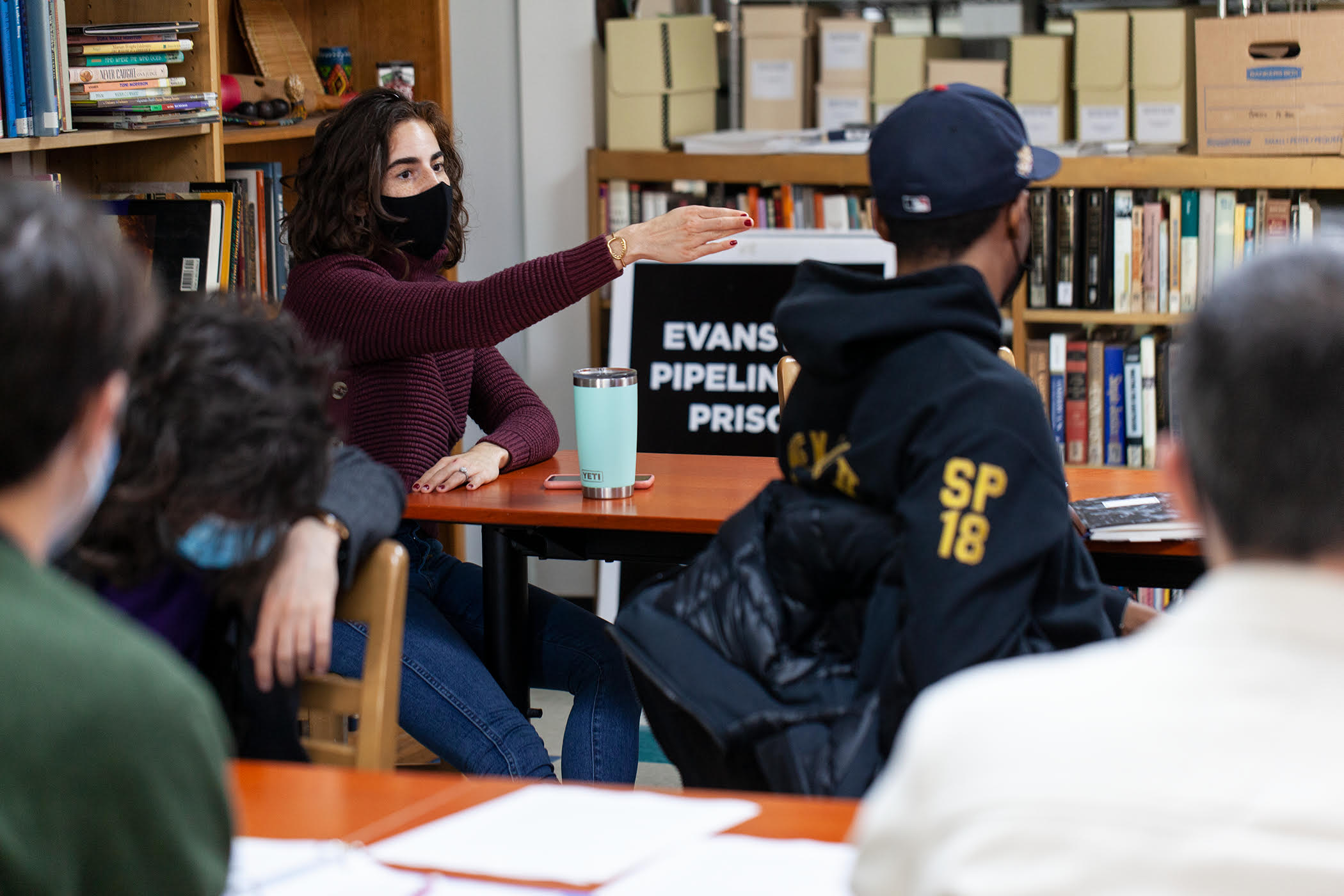

Alexandra Gonzalez at an oral history training session in November 2021.

PHOTO COURTESY OF SHOREFRONT LEGACY CENTER

After listening to multiple recordings, Gonzalez and her team realized the project had collected a rich local history. Black Evanstonians who were interviewed discussed disparities in education, redlining and community culture that younger residents might not have known about.

The project quickly expanded beyond an effort to connect people during a pandemic: It became an archive of historical information. After shifting its goal toward gathering more oral histories, specifically from Black Evanstonians, CCE sought out an existing organization in the community to help collect and archive these stories.

“We wanted to make sure that the project was carried out in a way that benefited the people we were interviewing, and that Black history could actually be taken care of and safeguarded by an organization that the community trusted,” Gonzalez says.

On the record

When Morris Robinson Jr., founder of the Shorefront Legacy Center in Evanston, was writing a series of articles about local Black history, he faced a debilitating lack of material. One organization he reached out to for his research presented him with a thin file folder labeled “colored.”

Shocked by the meager historical documentation on Evanston's Black community, Robinson started Shorefront in 2002 to educate citizens about Black history on Chicago's North Shore. Shorefront has amassed a significant collection of artifacts, documents, photographs and oral history interviews to improve access to local Black history.

Through its partnership with CCE, the organization seeks to grow this collection and involve Northwestern students in the process.

Robinson says his goal is to search for “hidden stories” — those that have been lost in family history or have only been told in passing.

“Our ultimate vision is to make local Black history common knowledge,” Robinson says.

Johnson, a former president of Evanston's NAACP chapter, believes in the importance of sharing his story for future generations.

“For us, [Evanston is] where we went to college, but there are tens of thousands of residents here who aren't transient in that sense. They spend their entire lives here. This is not their college community, this is their community.”

Michael Senko, Communication fourth-year

“History is always very important because if it's done correctly, it unites everyone with a sense of not only where we come from but where we are now,” Johnson says.

In 1958, Johnson organized the Chicago League of Negro Voters, a group that advocated for increased participation from Black citizens in city politics. In 1966, Johnson was a primary liaison in the historic meeting between Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Elijah Muhummad. Johnson also co-founded Path Press Inc., the country's first Black-owned publishing house. And, while attending Evanston Township High School, Johnson played on the football team and went to local NAACP meetings in his free time.

“There's always been some mystery around the Black folk on the North Shore,” Johnson says. “What [the project] did was solve a mystery.”

To ensure that these stories are preserved for future generations, Shorefront partnered with the Smithsonian Community Curation program, allowing the organization to digitize older interviews and transcribe new ones.

As part of her work at CCE, Gonzalez expects to publish a digital storytelling project with the oral history recordings on the Shorefront website by the end of the summer. The project will resemble a map, where users can click around to hear the stories that resonate most with them.

The Northwestern influence

The work of Northwestern volunteers has enabled Shorefront to record the stories of more Evanstonians and process their material more effectively.

“It takes a community to archive a collection,” Robinson says. “No one person can do it by themselves.”

The project is continually recruiting new volunteers. Robinson says that the experience serves as a learning opportunity for students who are looking to engage with communities in Evanston and Chicago.

Volunteers come from a variety of academic disciplines. Communication fourth-year Michael Senko applied to the program after he conducted linguistics research that studied the language patterns of Chicagoans.

During his research, Senko recalls feeling incredibly connected to the people whose stories he listened to and transcribed. He began searching for ways to replicate the experience, seeking opportunities to engage with Evanston residents outside of his Northwestern coursework.

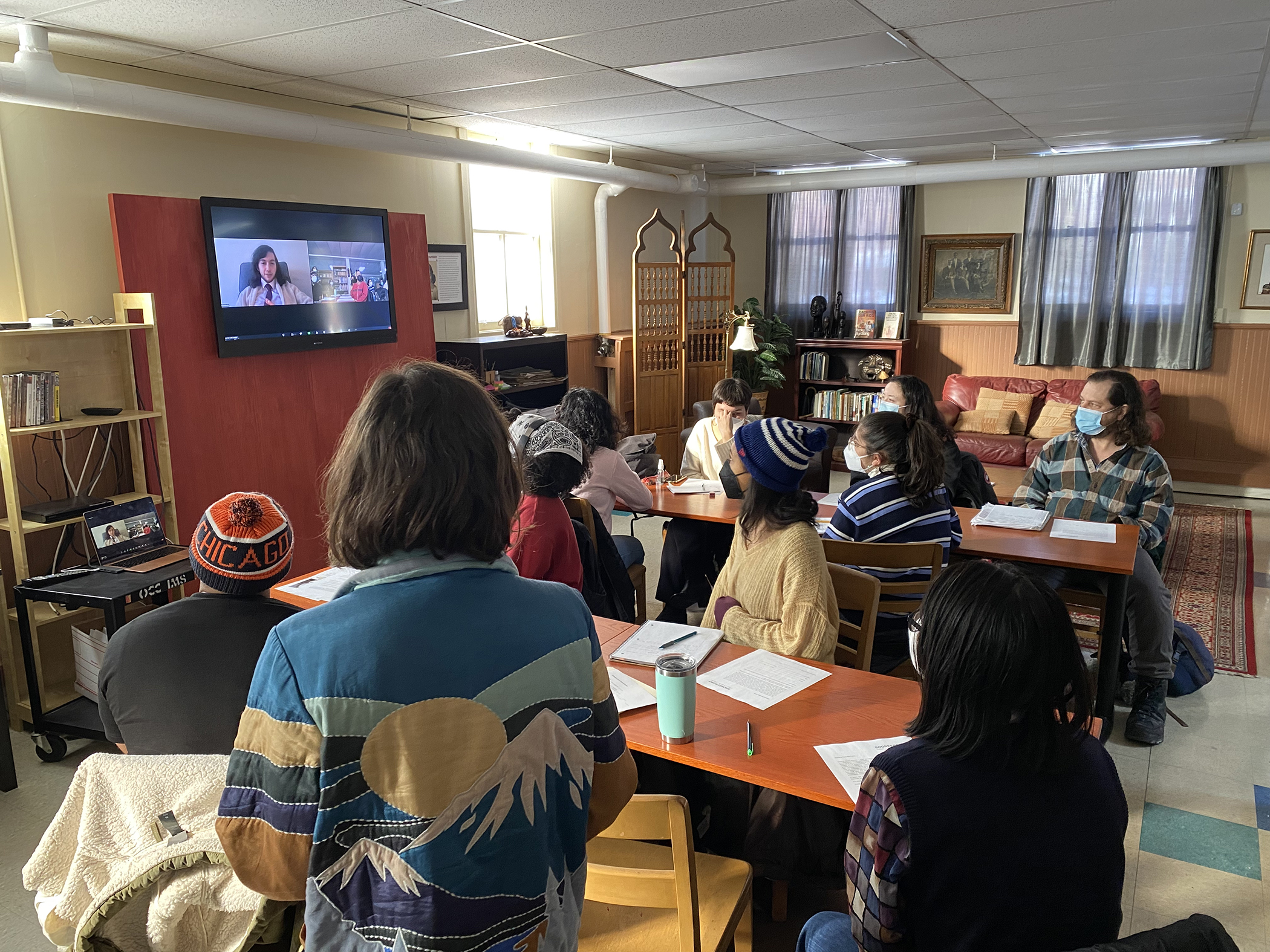

An oral history training session on February 18th, 2022.

PHOTO COURTESY OF SHOREFRONT LEGACY CENTER

After attending a two-hour oral history training session at Shorefront's facility, Senko is preparing to conduct his own interviews.

“Evanston is changing. Chicago is changing. I think it's really important that we document these Black residents' experiences who have been here their entire lives,” Senko says.

The students involved in the project hope to give back to Evanston in a tangible, lasting way.

“For us, [Evanston is] where we went to college, but there are tens of thousands of residents here who aren't transient in that sense,” Senko says. “They spend their entire lives here. This is not their college community, this is their community.”

Stories from dozens of Black Evanston residents have been documented through the project, and Gonzalez says she hopes to add hundreds more. As Northwestern students become increasingly involved in the collection and preservation of community history, Shorefront is growing closer to its goal of making local Black history common knowledge.

“The problem is that we are limited to the amount of time we have on this planet,” Johnson says. “We need to make sure that our lives extend beyond that."