WRITTEN BY

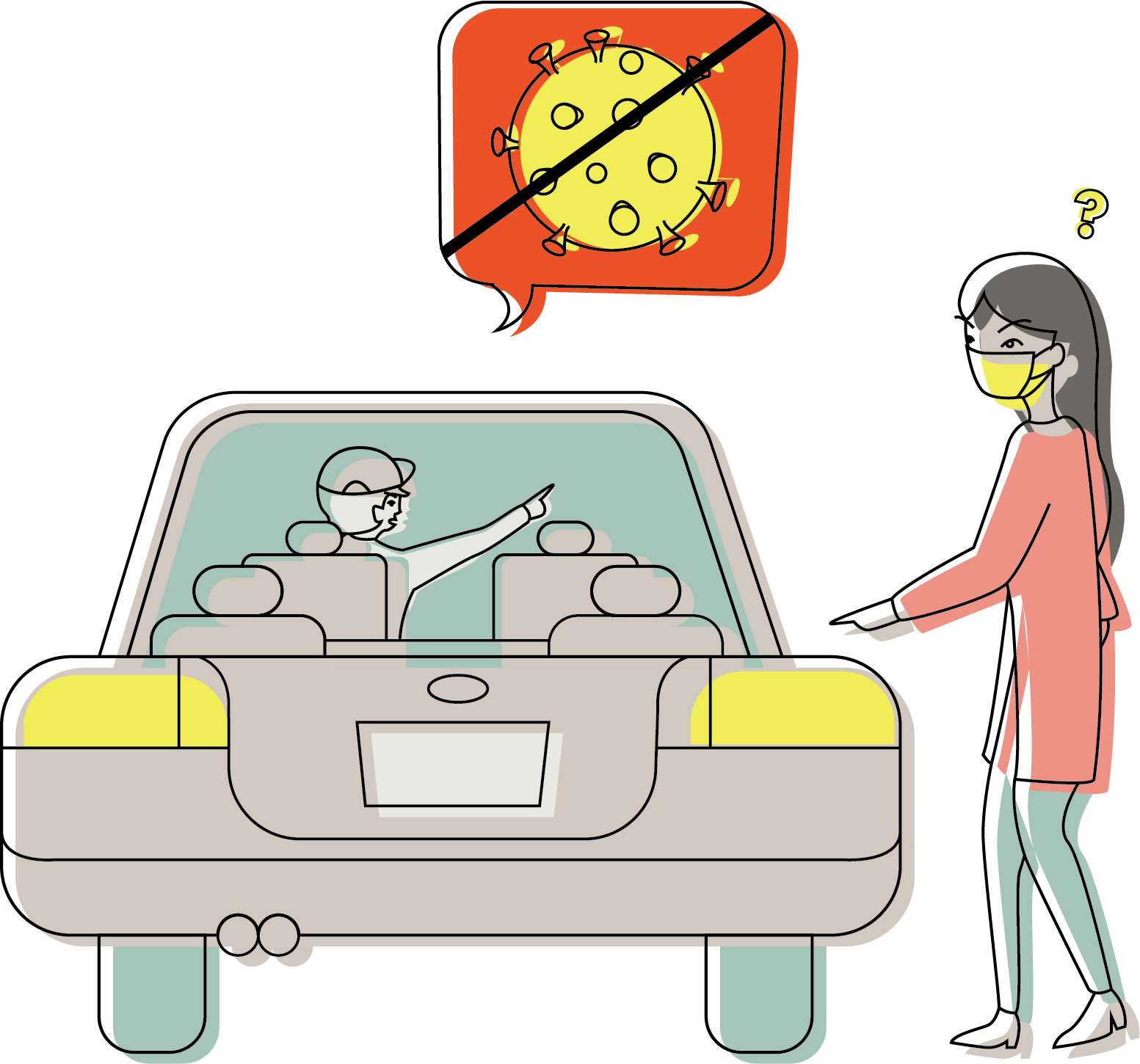

On March 7, Jonyca Jiao was supposed to see a show at the Windy City Playhouse. Jiao, a first-year theatre major from Xi’an, China, got in a Lyft — but the car didn’t start. Jiao looked up from her phone and noticed the driver looking at her in the mirror. The driver asked Jiao a question:

"Are you sick?"

Jiao tried to explain that the mask was a preventative measure. A little while after COVID-19 started spreading in the U.S., she had begun wearing masks her parents sent from China. But the driver didn’t trust Jiao and told her she had to get out of the car.

“I froze,” Jiao says. “I didn’t know how to react because it never happened to me before. I wanted to argue with her after that. I explained to her that this is something I do to protect myself, not that I have diseases. I understand why she did that, but it was discrimination.”

Racism towards Chinese people, such as Jiao’s exchange, became a pervasive reaction to the pandemic’s spread. While studies say flights from Europe carried COVID-19 to New York, President Donald Trump was slow to enact a travel ban on Europe, instead focusing travel restrictions on China. Political leaders (including Trump) called COVID-19 the “Chinese virus,” against the advice of the World Health Organization. Locally, The Daily Northwestern reported “Chinese virus” was spray-painted over a Chinese character on a Lakefill rock, and graffiti reading “Make China Pay” surfaced in an Evanston bus shelter in late March.

While the coronavirus is novel, subsequent anti-Chinese sentiment is not. Rather, the COVID-19 pandemic has incited a re-emergence of centuries-old stereotypes and tropes of anti-Asian discrimination.

Asians in America have been accused of carrying diseases since their initial emigration to the U.S. in the 19th century, according to Asian American Studies Professor Ji-Yeon Yuh. American public health authorities in the 1800s believed Asians — particularly Chinese people — carried the bubonic plague. Yuh says the stereotype of the “dirty, diseased Asian” continues today; she believes the media has often targeted Chinatowns for public health violations.

“[Anti-Asian racism] always existed, and it’s being publicly expressed in harassment and violence,” says Yuh. “There are these peaks where it’s noticeably worse. This happens to be one of those peaks.”

Historically, when racism targets specific groups of Asians in America, the broader Asian American community suffers from discrimination. In 1982, outrage regarding the death of Vincent Chin sparked an Asian American civil rights movement. Anti-Japanese sentiment permeated Chin’s home city of Detroit due to the perceived loss of auto industry jobs to Japan. Although Chin was Chinese American, two white men murdered him with a baseball bat while shouting racial slurs, assuming Chin was Japanese. The two men never went to jail for their actions.

Today, generalization of Asian nationalities puts Asian Americans at large at risk for discrimination.

“I feel like my identity, my nationality, was especially targeted,” Jiao says. “I think Asian American communities were an extension of that.”

The Hill reported anti-Asian hate crimes skyrocketed as the pandemic hit the U.S., reaching 100 per day in March. In one of the most severe cases, a Texas man stabbed two Burmese American children and their father thinking they were Chinese and spreading the coronavirus. The children were 2 and 6 years old.

Abbey Zhu, the president of Northwestern’s Asian Pacific American Coalition (APAC), believes the language connecting Asian Americans with COVID-19 plays a part in these violent acts.

“Your words affect the lived experiences of Asian Americans and they affect the way you think of Asian Americans ... and that can justify stabbing a 2-year-old Burmese child,” Zhu says.

Amid COVID-19, Zhu has provided emotional support to APAC members and connect them with ways to enact change, like by calling members of Congress to ask that they create a stimulus bill that includes undocumented immigrants. However, she says she has felt helpless to change the political reality at times.

“The U.S. has many systems that are blatantly being shown that they’re failing right now, and it’s hard to feel like you can change those systems,” she says.

Zhu fears her father could become a target of harassment, especially because he wears a mask when shopping for her family’s groceries. She isn’t alone. Many Asian Pacific Islander Desi American (APIDA) students at Northwestern express a sense of discomfort stemming from anti-Asian racism’s increased national visibility.

Weinberg first-year Angela Liu believes her Asian identity has always been one of the first things people notice about her. But now, during the pandemic, she thinks people put her race before any other aspect of her identity.

“It’s the most prominent thing, and everything else sort of comes after that,” she says. “I have to go out of my way to prove I’m not sickly. It’s just making extra steps so other people can feel more comfortable, which is really unfortunate.”

Medill first-year Anushuya Thapa, a Nepali international student, says while she hasn’t felt directly targeted by anti-Asian racism, attitudes in Evanston appeared to change during her last few days on campus.

“If I saw someone who was more looking the part of an East Asian American or a Southeast Asian American, I could feel them getting stared at,” Thapa says. “That would always make me feel uncomfortable.”

As president of Asian-interest sorority Sigma Psi Zeta, third-year Minna Ito, says she sees herself as less East Asian-passing. Ito, who identifies as Filipino and Japanese, feels this makes her less vulnerable to harassment than some other members of the APIDA community, which allows her to support more directly targeted groups.

“In contexts where people see me as more Southeast Asian or Filipino, I may have the privilege of not having to be as hyper-aware of how I look,” Ito says. “It puts me in a position where I could show up more for my communities compared to people who may be more vulnerable during this time.”

Ito does not believe showing up for her community means changing her behavior to appease other Americans. In April, The Washington Post published an op-ed from former Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang that argued Asian Americans should demonstrate their “American-ness” to the world through acts such as wearing red, white and blue.

“A lot of my friends realized how messed up that was,” Ito says. “We don’t have to go out of our way to prove our humanity by any means, but we should feel empowered to support each other.”

Since social distancing has prevented APIDA groups from gathering in person, support has often taken the form of virtual meetings. Shortly after the pandemic began to spread in the U.S., SESP second-year Sydney Gil attended a Zoom call facilitated by the Korean American Grassroots Conference, a civic engagement organization.

“They asked, ‘Have any of you guys felt uncomfortable being in public or unsafe?’ And almost everyone — if not everybody — raised their hands. Of course we feel uncomfortable,” Gil said.

Asian-interest organizations at Northwestern are also grappling with how to support their members. One of the largest Asian-interest organizations on campus, the Chinese Students Association (CSA), held a virtual dialogue in April among its members about COVID-19 and racism. While CSA doesn’t typically host events discussing social issues, its members appreciated the opportunity to discuss how they felt in a safe environment.

“It was honestly really well done because everyone is so comfortable with each other,” says Liu. “Personally speaking, if that comfort level wasn’t there, it’d be harder to speak up.”

Isabell Liu, who facilitated the event as CSA’s cultural chair, says the increase in overt anti-Asian racism also amplifies the impact of microaggressions toward Asian Americans and Asians in America.

“People have always been racist. I don’t mean that makes it okay, but I think the context matters a lot too,” Isabell says. “You could have made a Sinophobic joke two months before COVID-19 got to the U.S. and it would have a different impact than if you made it now. It’s volumes louder.”

To Yuh, many Asian Americans “excuse the racism that they see and experience around them, or [don’t] even see it at all” because of two tropes: the “perpetual foreigner” and the “honorary white.”

The myth of the perpetual foreigner frames Asian Americans as outsiders in the U.S. who will never truly belong in the country. Paradoxically, Asian Americans are also portrayed as “honorary whites” because they are falsely perceived as being higher-achieving than other minorities in America. These two myths, according to Yuh, create an “ambiguous racial location” that allows Asian Americans to see anti-Asian racism as “not as bad as what some other people get.”

“What COVID-19 and the rise in anti-Asian harassment and violence has done is, it makes it more difficult to engage in those kinds of denial,” Yuh adds. “It’s much harder to say ‘We don’t experience racism, it’s not a big deal.’”

Watching the pandemic unfold, many APIDA students wished for more solidarity within Northwestern’s APIDA community.

“The APIDA community at Northwestern feels very fragmented,” Ito says. “I hope in the future, we find a way to more actively build coalition in the way that we’re not just throwing the label around, but actually showing up for each other.”

A number of APIDA students have also connected their own experiences during this pandemic to those of other minority groups on an everyday basis.

“I was thinking about how people — who they are, their skin color or where they came from — they probably get that kind of treatment every single day of their lives,” Jiao says. “This is just a small proportion of what they go through. [The Lyft refusal] kind of taught me a lesson.”

Many Asian American activists hope Asian Americans will not just feel anger at the racism directed towards them, but at systemic racism against all minorities.

It’s terrible. But it is a good time to use our oppression and how we experienced oppression to think about other groups in their oppression and how we can help.

-- Isabell Liu, CSA Cultural Chair

“What is happening to the Asian American community right now is a reality most of the time for Black and brown communities,” Zhu says. “Let this moment be a recognition: We are all affected by and in different ways complicit in maintaining a system that arranges people in racial hierarchy that justifies violence against nonwhite communities. So don’t be selectively mad.”

While Isabell Liu says there’s nothing good about the current situation, she hopes it will create solidarity between the APIDA community and other marginalized groups in the U.S.

“This whole thing sucks. It’s terrible. But it is a good time to use our oppression and how we experienced oppression to think about other groups in their oppression and how we can help,” Isabell says.