Students from Hong Kong reflect on ongoing protests.

At the beginning of his summer, Weinberg second year Isaiah Jones walked on the highway of Causeway Bay, one of Hong Kong’s shopping districts, alongside elderly men and women and their grandchildren crying for their futures at the top of their lungs. The demonstration was one of the early protests as part of the city’s anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill (antiELAB) movement.

As the protests in Hong Kong continue, Northwestern international students are concerned about the future of their home and city.

The antiELAB protests began peacefully in June in response to a bill that would have allowed anyone in the city to be extradited to mainland China and tried under China’s judicial system. Under the bill, authorities would be able to detain people for committing certain crimes. The chief executive of Hong Kong, Carrie Lam, proposed this bill after a man from Hong Kong allegedly murdered his girlfriend while in Taiwan, but Taiwan was unable to put him on trial because officials were not able to extradite him from Hong Kong.

As part of the “one country, two systems” policy, Hong Kong’s courts are independent from China. Critics of the bill were concerned it would infringe on the city’s sovereignty and target political activists.

“The extradition bill was just terrible. It just goes against the freedoms that I’m used to, living in Hong Kong,” Jones says, as he explains why he decided to protest. “It’s like fighting for my city, and I’m fighting for the identity of my city.”

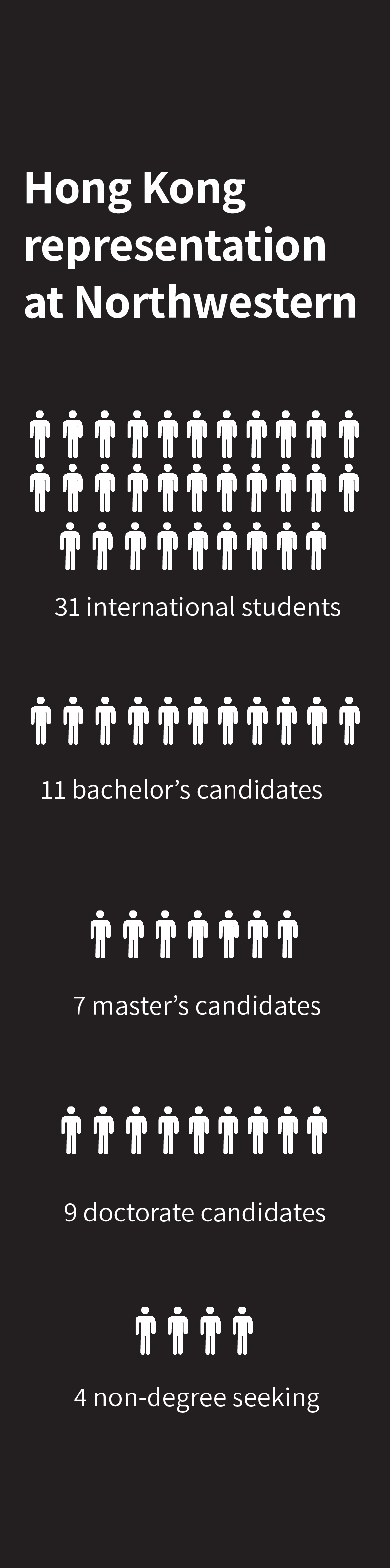

Northwestern has several dual-degree, student exchange and joint degree programs with universities in Hong Kong, including the University of Hong Kong and the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. At Northwestern, there are 31 international students from Hong Kong currently attending the university, and 24 students studying abroad in the city during fall quarter.

Graduate students in the Integrated Marketing Communications Master’s Program planned to travel to Hong Kong and Singapore in September. In light of the protests, however, students only attended the Singapore portion

of the trip.

Millions of people in Hong Kong have been showing up to local demonstrations. Since the beginning of the protests, violence between protesters and the police has escalated. Lam withdrew the bill in early September, but the protests have grown into a larger movement for reforms. Protesters are now demanding an investigation into accusations of police brutality, amnesty for those arrested during protests, universal suffrage and that government officials stop using “rioters” to describe protesters.

Police have tried to deter protesters by using tear gas and rubber bullets. After this became more common, Jones no longer felt that it was safe for him to protest.

“Growing up, Hong Kong was known as the safest city in the world,” Jones says. “Seeing tear gas in the street, seeing train stations really close to my apartment, close to our house, absolutely destroyed, graffiti on the streets everywhere. It feels like a very different city.”

Despite the protests, Medill Assistant Director of External Programs Kathleen Lee is hopeful that Hong Kong will be a location for future academic programs. Still, for international students, the connection to the city is much deeper and more personal.

SESP first-year Charlotte Wong also participated in the protests early on in the summer. During these protests, she describes the unity she felt among Hong Kong citizens.

“We had more patience than on an average day,” Wong says. “People

are helpful. They would be really willing to help and give out water, supplies, help recycling and help take out the trash. You feel like people care, and people were caring for each other.”

Although Wong didn’t face any physical danger during the protests, this wasn’t the case for all student protesters. Communication third-year Justin Liu attended several protests throughout the summer, once even in the midst of tear gas.

“There was fear,” Liu says. “Mostly, I needed to get out of the situation. If there’s any primary emotion, it would be cowardliness. Because there are people who are so in front and so brave and ready to fight for what they believe in. Then, there are people like me who are behind and worrying about personal safety, worrying about this, worrying about that. My primary emotion over the last few months has been guilt more than anything else.”

Over the summer, Liu stayed involved in the protests, in person and online. To support the protests, he participated in what he describes as “propaganda warfare,” or 文宣, which involves making posters, spreading information online and on social media, and translating documents from Chinese to English. But Liu feels like he hasn’t done enough to support the movement. Liu describes himself as feeling “middle class or upper-middle class guilt.” Since he has a British passport, he feels that he could push more boundaries and even break the law.

Between his guilt and the violence, Liu’s mental and physical health suffered. Now at Northwestern, Liu says he doesn’t know how to cope with the mental toll, and he doesn’t think that CAPS will be able to provide any services that will help him with the situation in Hong Kong. “I’m just choosing to compartmentalize,” he says. “I’m being more and more distant from the events happening because there was so many atrocities happening every day.”

As the protests have intensified, though, Liu says the situation now has his full attention. “[It is] difficult to keep up [with the news], but nonetheless my moral duty to do so.” In terms of what the university can do to support students, Liu expressed his desire for a discussion or panel about the topic and contacted faculty but has heard no response. Wong urges students to keep up with the protest news.

“I want people to be informed so our story doesn’t die down in the midst of everything.” While there is increasing polarization, not all students are protesting. Hong Kong international student and Weinberg fourth-year Bernetta Li has not participated in any protests. She does not think of herself as a “super political person” and recognizes her privilege in that she is not forced to pick a side between the protesters and police. Although she has not been active in the protests, Li still sympathizes with the young protesters and wants the government to address issues of police brutality as well as the rising cost of housing.

As for Hong Kong’s future, many international students hope to see the government give into the demands of the citizens. Although the slogan of the protests has become “光復香港 時代革命” (“Liberate Hong Kong, revolution of our times”), both Wong and Liu recognize that the primary goal of the movement is not to declare Hong Kong independent.

Though Hong Kong independence is not the priority, some students feel culturally separate from China. Liu and Jones both say they are ethnically Chinese but define themselves as from Hong Kong. As the protests continue with no clear end, the future of the city and of Hong Kong international students remains uncertain. Some students won’t be returning back to the city after graduation. As an RTVF major, Liu does not see many opportunities for work in Hong Kong. Li, who plans to work in finance, feels that the markets are too unstable and that the city is less safe because of the protests. Although some students don’t plan to move back to Hong Kong, they are still attached to the city they grew up in.

“If my home doesn’t have a future, then how do I have a future?” Liu asks. Liu says that the world is undergoing shifts in power and international relations.

“This is essentially a fight for the identity of Hong Kong,” Jones says. “I don’t know what Hong Kong’s going to look like after these protests.”