To an observer, it can be difficult to understand why a student undertakes the grueling year-long commitment of an honors thesis. It’s an endeavor that can easily double their senior year workload and become yet another source of stress on top of an already hectic schedule.

Some thesis students, like McCormick Industrial Engineering fourth-year Dawson Ren, feel invested in the results of their research through a personal connection to the subject matter. Others, like Weinberg Computer Science fourth-year Will Hoffmann, were ready to take on research of any kind for the opportunity to work with a favorite professor or have a trial-run of the graduate school experience.

Theses look wildly different from each other across disciplines. By the end of the year, Weinberg Art History major fourth-year Elizabeth Dudley will have produced a 30-page visual exploration that has almost nothing in common with Weinberg Neuroscience fourth-year Jenna Lee’s data-filled laboratory reports.

But there is a common thread: curiosity. It’s the only thing that could possess someone to voluntarily spend grueling hours taking samples in a lab, combing through the reference library or parsing through abstracts to find the missing piece of their bibliography.

Here, four senior thesis students with interests in disparate fields explain in their own words what they’re researching and why it’s worth an entire year of nonstop work.

Gearing up

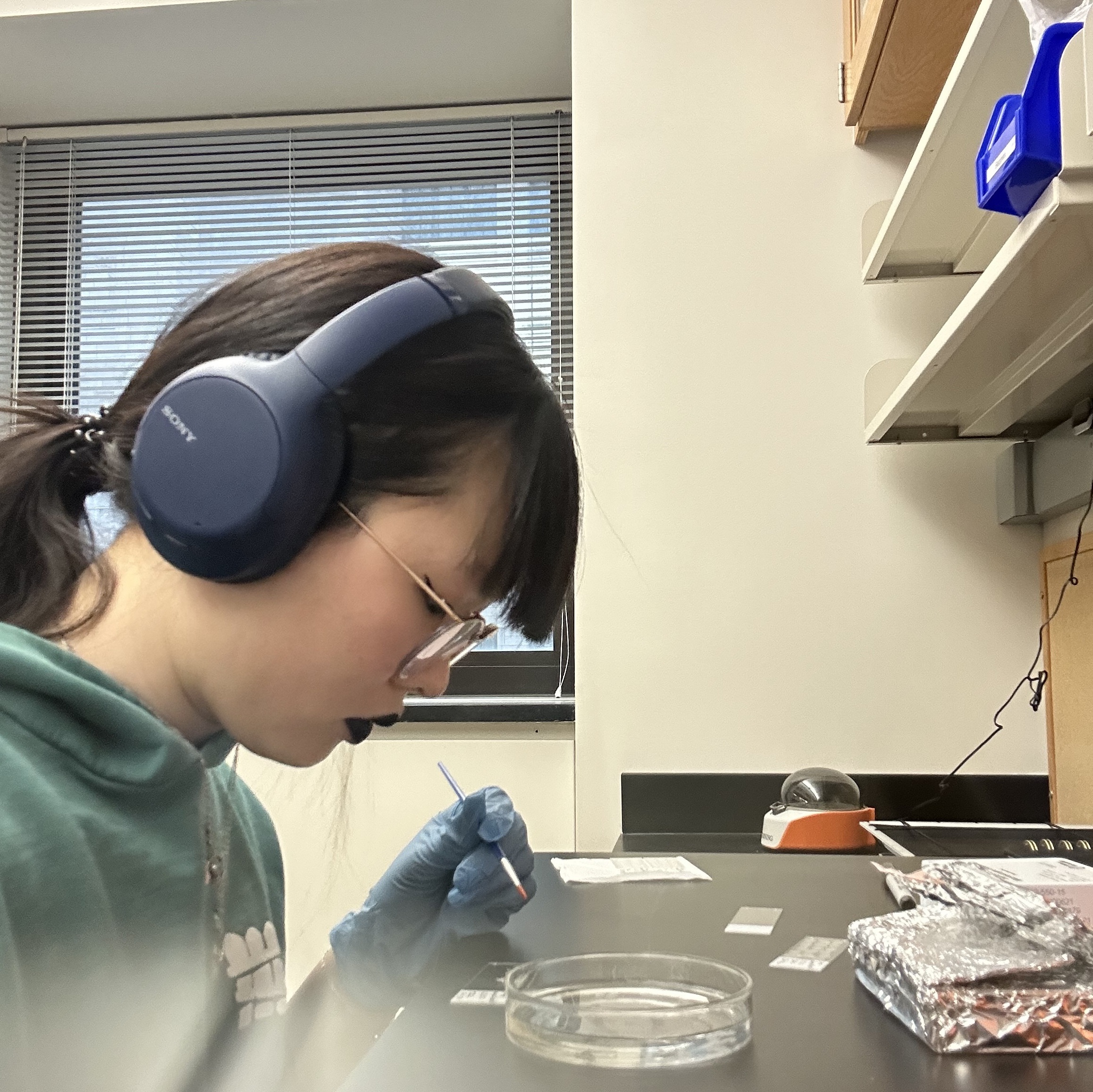

Jenna Lee stumbled onto her neuroscience thesis somewhat by accident. She had been doing research in an on-campus lab since sophomore year, but when the project packed up and moved to Michigan over the summer of 2023, she was suddenly without a lab project right when her research was supposed to be taking off.

“I always knew I wanted to do a senior thesis, but I felt like because of who I am, I wanted to be doing the research while I was writing it,” Lee said. “I also wanted to have a lot of open communication with my mentor, and I just knew that wasn’t going to be viable with the lab that moved.”

After shopping around available labs – “throwing herself out there” – Lee landed in a lab that was researching links between social interactions and neural circuitry. While she said this wasn’t her personal niche interest, she has become more invested in the results over time.

Elizabeth Dudley was similarly introduced to art history by accident, through a freshman year theater course on costume design. She then took an Art History class in the spring called “Fashion, Race, and Power,” and, enamored, immediately declared her major.

“It was the origin of me learning about this entwined point of textile history, visual culture, and the idea of fashion as another form of creative expression,” Dudley said.

This introduction has manifested into a thesis on the internet aesthetic known as “cottage-core” in which Dudley dives into its visual and artistic references, its roots in whiteness and its idealization of rural life.

She had been involved in independent research on the topic since high school and, referring to herself as a “pedantic nerd,” said she always knew she wanted to write a thesis.

“I love to get into the mess of things, and how many opportunities in life are you going to get to devote this much time to a project?” she said.

Will Hoffmann arrived at his Computer Science thesis by following a beloved mentor, Computer Science Professor Wood-Doughty.

“I really loved his teaching style,” Hoffmann said. “So I was like, ‘I don’t really care what I do my thesis work in – I just wanted to work under him.’”

Where Dudley’s humanities thesis was based almost entirely around the selection of a topic she wanted to learn about, Hoffmann thinks about it a little differently. He said computer science is unique because the methods often matter more than the actual substance.

“It’s just like, I have a problem in front of me and I try to solve it. That’s what I enjoy.”

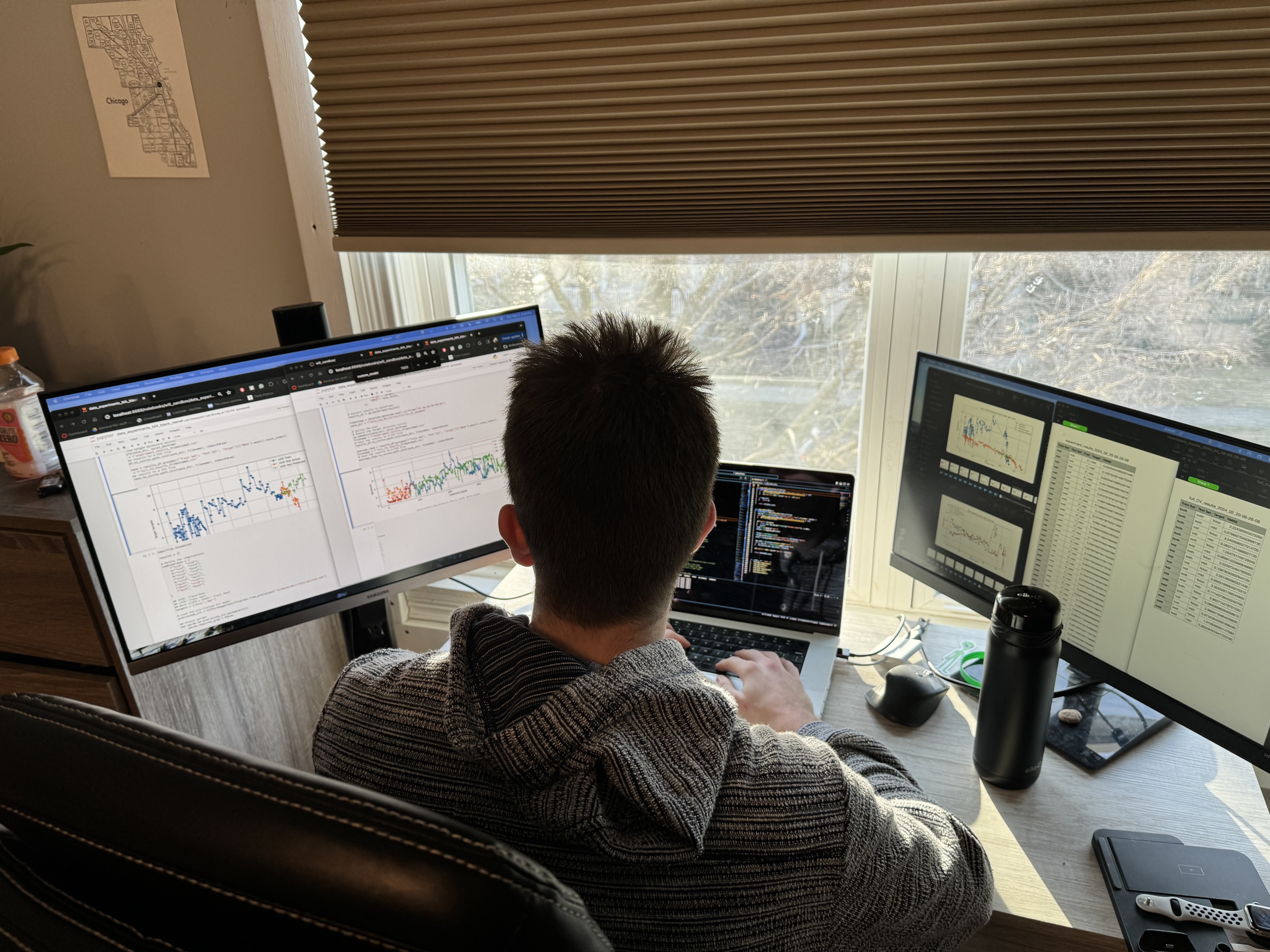

Hoffmann is building a model to accelerate the process of extracting measurements of mud samples from different locations. The model will learn how to derive certain measurements on its own from manually-obtained data.

He noted that although it’s not geological and biological processes he’s interested in, he does like that it has an environmental component.

“It’s definitely broadened my horizons,” he said.

The data obtained by Hoffmann’s model can be used to understand the climate of millennia past, as well as how it might change in the future.

He also noted that because geoscience as a field is a bit behind in its use of machine learning, there’s a lot of room to add to the field’s research.

“That’s something I appreciate,"Hoffmann said. "It’s cool to be on the cutting edge of a field that might not have as much exposure.”

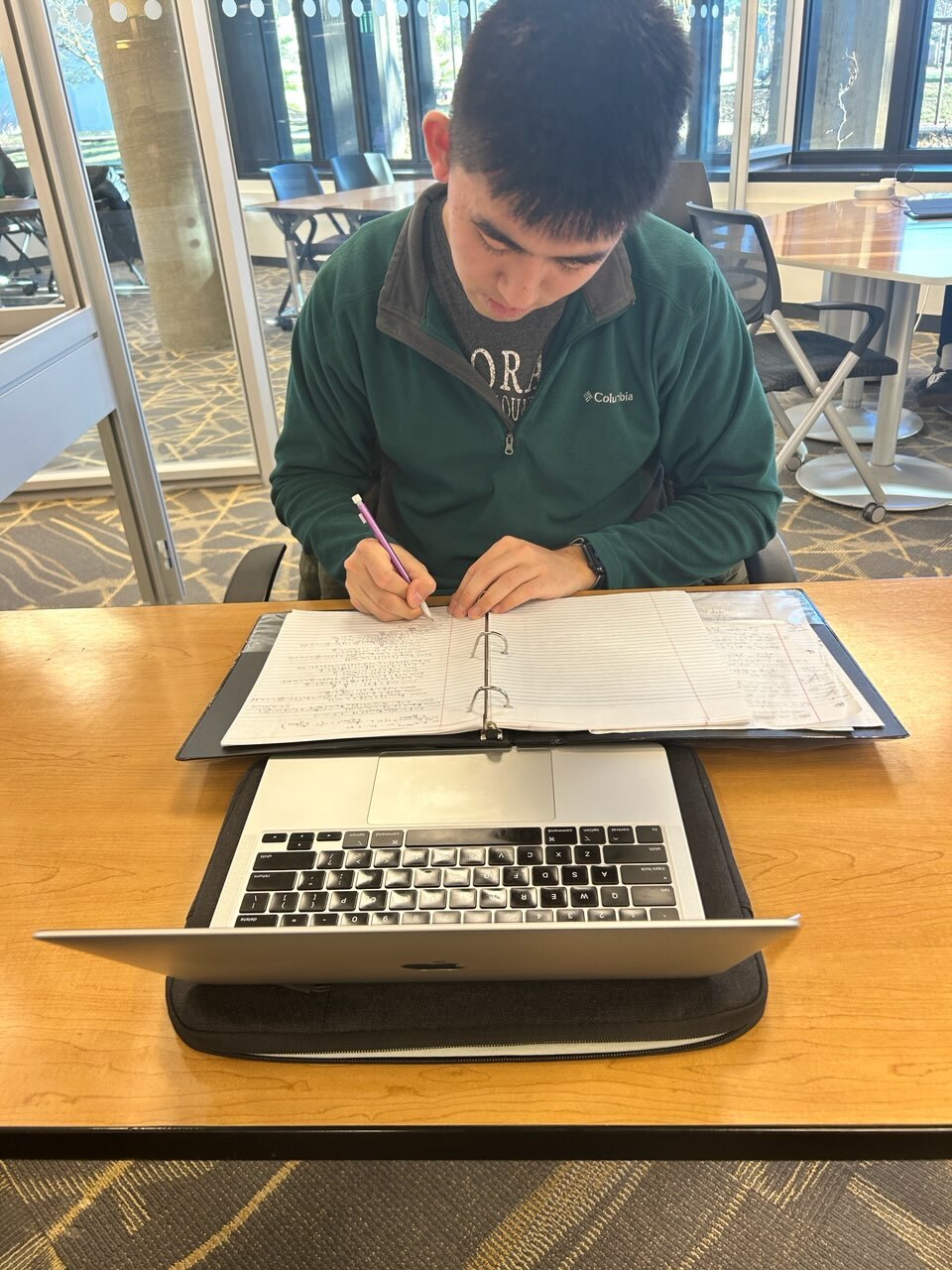

On the other end of the spectrum is the intentionality with which Dawson Ren approached his Industrial Engineering thesis topic.

Ren had been volunteering at a local food pantry once a week for over a year, which was the impetus for his thesis idea.

“Industrial engineering is about trade-offs and developing algorithms,” Ren explained.

His goal is to develop an algorithm that can find the most efficient way for trucks to drop off food at food pantries around Chicago.

“We collect data from different pantries, find out which ones are more consistent with the amount of food they ask for, and which are more variable," Ren said.

Ren had originally planned on taking it easy his fourth year, but realized his plan to go right into grad school would benefit from some previous experience with high-level independent research.

Once each student had finally settled on a topic, it was time to get started. But for a project this massive and long-term, it can be difficult to know what “started” even means.

Burnout

“I’ve definitely put as much work into this as an extra class or two, especially this quarter,” Hoffmann said. “It’s frustrating at first to not feel like you’re going anywhere, but I also feel like it’s been very helpful for developing patience.”

Fall quarter tends to be a gearing-up period for thesis students – a time to refine their topics and collect literature. Winter quarter ramps up quickly. It’s crunch time once January rolls around, and there are no breaks from thesis work.

Balancing multiple additional classes’ worth of work is, of course, no simple task. On the lighter weeks, lots of thesis progress can be made. But during Northwestern’s notoriously lengthy midterm season, it inevitably falls by the wayside.

“I’m always spending less time on this than I’d like,” Ren said. “There are always other commitments with sooner deadlines.”

Lee is feeling especially apprehensive about the written component of her thesis, which is understandably outside her comfort zone compared to the lab work she’s been doing.

“I feel like I’m a little bit delusional, because I feel like things are going well, but I also know that I really need to pick up the pace,” she said.

Looking ahead to the volume of tasks left for them to tackle is daunting, even when they’re making consistent progress each week, according to Dudley.

For her, the amount of literature to tackle was the most cumbersome.

“There was a lot of anxiety with wrapping my head around, ‘Oh my god, I have to read through all this literature,’” she said.

Things don’t always go according to plan, either. Understanding what it means to be solely responsible for a research project comes gradually as they learn the difference between their previous classwork and an honors thesis.

“In class, it’s really easy to get a 90 percent accuracy and predict things really perfectly,” Hoffmann noted. “But in the real world, there’s a lot more noise and variation, so it will be basically dependent on how much effort I put in.”

Finding their stride

Some weeks are more fun than others, according to Hoffmann. In late January, for example, he was understandably frustrated when he learned he needed to completely revamp his model.

Other weeks are satisfying in a way that can’t compare to anything else they’ve worked on at NU. Dudley is finally about to finish laying out her base of scholarly literature and get to the core of her visual analysis. Lee just got her first round of results back from her lab mice’s brain scans.

“I’ve felt so supported by my PI [Principal Investigator] that I’ve been really enjoying the process of just learning about everything and trial and error,” Lee said. “Even when we get results that we weren’t expecting, it’s been really illuminating to learn what’s causing those errors,”

Ren’s breakthrough moment came when he proposed taking a different approach than in previous research. His entire project is based around the idea of equitable food distribution, so it’s important to have a specific definition of what “equity” means.

“The current definition of equity is very strict. I thought, ‘If we relax it, can we come up with different algorithms that work better?’” Ren said.

Dudley perfectly and succinctly captured the experience of a winter quarter thesis student.

“I absolutely love what I’m doing and I think I’ve hit a good stride, but I also have wrist braces in my bag because I strained my wrist tendons from typing too much," she said.

New discoveries

Writing a thesis is an all-encompassing experience. Almost none of the work happens sitting in a classroom. Sometimes, the research takes a student even further than the annals of Main or the labs of Tech.

Dudley said that a big part of the Art History thesis is visiting archives.

One of her fellow thesis students traveled to France to see a tapestry relevant to her research. Dudley ended up traveling to the Minneapolis Institute of Art to get her own in-person exposure to the 18th-century fashion magazines and textiles that would become a central part of her work.

“I think there’s something so interesting about getting to unpack the visual roots of this,” said Dudley. “With cottage-core, everything is reference-based. Which isn’t a bad thing — we live in the era of remix culture — but what I love is getting to dig into those materials and see why something is being referenced in the first place.”

Lee’s project also requires her to take her learning outside of the classroom.

In a lab in Chicago, Lee conducts her social hierarchy and isolation experiments with lab mice. According to Lee, she sometimes works in the lab for up to 18 hours a week.

“We take thin slices of the mouse brains, stain them with a marker to see the neural activity and see what areas and neurons are activated when they’re socially isolated or not," she said, adding that the imaging takes three days. “The research is slow and can’t be sped up, because the biological processes can’t be sped up, and we can’t speed up the isolation period, either,” Lee said.

For Ren, the possibilities of what his thesis might produce are a huge motivator.

“I want to beef up my numerical experiment section to show my theorem works across different circumstances, like at pantries in Chicago and New York,” Ren said.

His personal involvement with the issue of food scarcity means this project is a long time coming.

Hoffmann, meanwhile, decided to take the plunge last spring, at the end of his junior year.

“I’ve never done an independent research project,” Hoffmann said. “What I put into this is what I get out of it. It’s definitely an exercise in self-control and intrinsic motivation.”

Connecting with mentors and looking ahead

Dudley and Lee have both known they were going to write a thesis for years, but they didn’t know whether the real thing would live up to the idea they had in their heads of an intellectual, academic deep-dive.

“It’s been an experience that I’ve wanted for a long time,” said Dudley. “And I’ve learned through a lot of other experiences at Northwestern to know when the struggles are worth it. And so even though the process is a big challenge and there have been setbacks, it’s helped me to grow – not only as a researcher but also as a person having fun with this project.”

Lee shares Dudley’s satisfaction with what she’s experienced of the thesis process so far.

“It’s been a really affirming experience for me,” Lee said. “My eventual goal is to return to academia and be a professor – I love teaching and I love research. Before doing this, I was like, ‘I think this is my goal, but is it really?’”

However, Lee says that self-doubt was significantly relieved by the thesis work itself. She said the thesis is often a student’s first real opportunity to see a research project through from beginning to end.

“A lot of undergrad research is jumping into the middle of a project to help out, and then jumping out before the writing part starts,” Lee explained. “But this is, on a smaller scale, what I would be doing as a grad student, or eventually as a professor. Feeling that excitement toward the whole process, despite it not being my personal interest, is reaffirming to me that this is what I want to do.”

Ren hadn’t been planning on writing a thesis for quite as long, but he said he’s glad it turned out this way. He said seeing the community impact is gratifying, and using IE to enact social change is "amazing.”

Plus, the process is a huge asset for grad school planning, according to Ren.

“All the people I’m interviewing with for grad school have written papers like these,” Ren said. “They’re as awesome in real life as they seem on paper. It’s a small community, so they’re really encouraging. They’re super nice.”

Through the ups and downs, Hoffmann said it’s taught him a new level of rigor and attention to detail. He said that as someone who has been interested in research for years, even if he does not attend grad school, the end product of the thesis will have been worth it.

Despite the grueling workload, these students see plenty of good reasons to take on an honors thesis. Their unanimous conclusion is that the work is worth it.

"It’s a good kind of trouble," Dudley said.