Knowledge is power, right?

As life happens on both a global and local scale, we have almost real-time access to information, with much of it coming from unverified social media postings. Some of this is accurate and beneficial, such as being alerted to a school shooting or terror attack; a lot of it is counterproductive, speculative and potentially dangerous. Because we are bombarded with so much new, often negative, information every day, our worldview has become more pessimistic. We perceive the present as worse than the past (even when this isn’t true) – a “condition” known as Mean World Syndrome.

Given our relationship to information, especially toward negative information, it might not be a great idea to give everyone a platform to discuss crimes, emergencies, accidents and other happenings around them – especially when panic or plain malignancy can cause misinformation – but that is exactly what social crime reporting apps like Citizen and Nextdoor are doing. In fact, they’re promoting these discussions, with the usual results of racial profiling despite the efforts of Nextdoor and Citizen to avoid this. Incredulously, access to information is promoting everyday citizens to run towards the fires, not away from them.

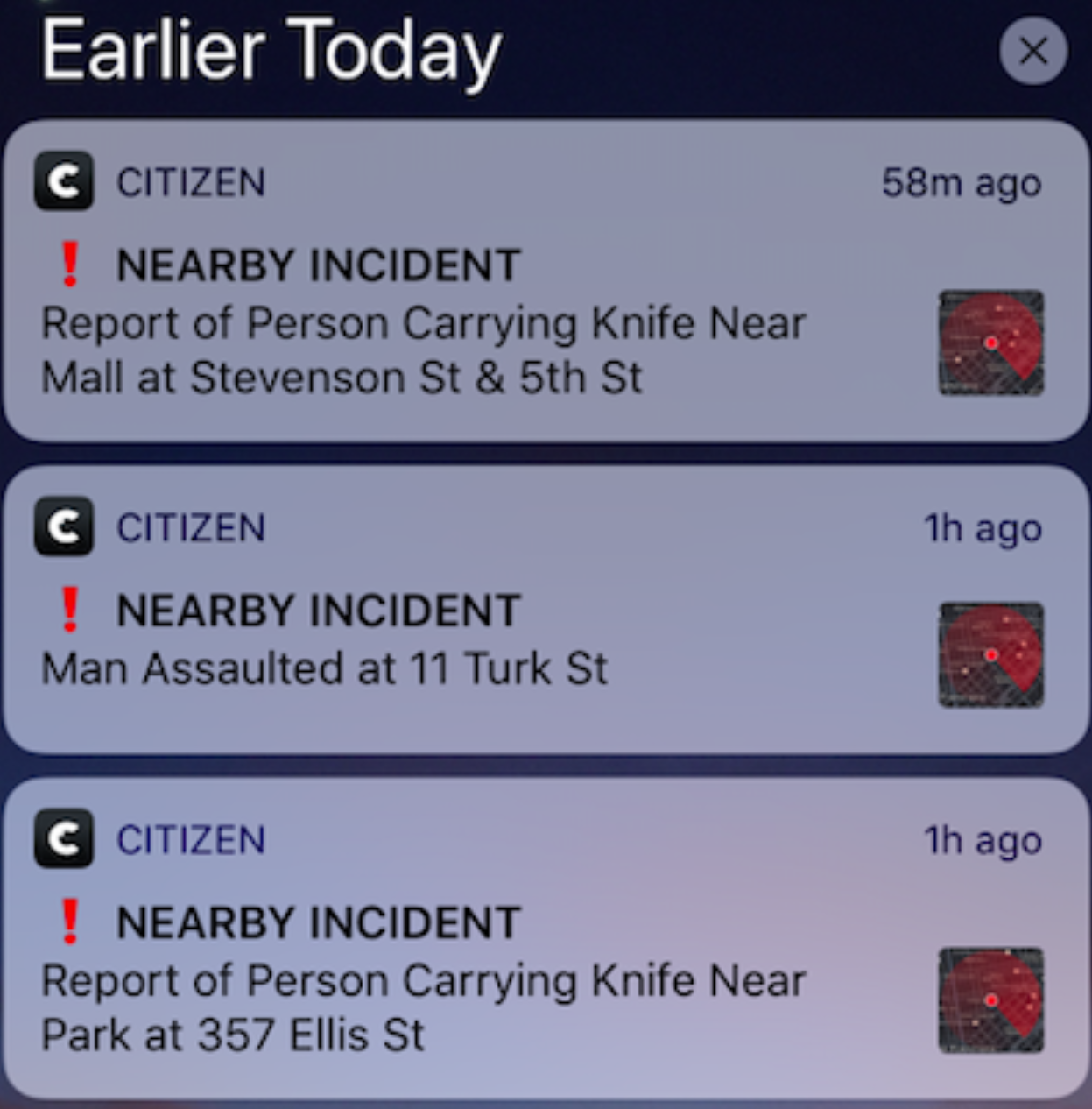

A quick rundown of Citizen and Nextdoor: Citizen compiles data from police scanners, emergency radio frequencies, and civic alert sources and places it on a map for users to see what is happening across an entire city. Nextdoor is a neighborhood watch meets Silicon Valley venture where people can join their neighborhood group to discuss safety in addition to organizing community events. Effectively, it’s a neighborhood Facebook group with a lot more razzle dazzle. With these apps, users have immediate access to crime and emergency-related news throughout their area. Not only that, these events can be recorded and transmitted through the app “if you’re in a safe place” to do so. Whether that’s a fire down the street or a murder 10 miles away, both appear on the app, so you have unfettered access to the goings-on around town. While knowing about the fire might help you plan out your morning commute to avoid emergency vehicles, the murder is out of your control, not near you and as a result, it only serves to heighten fear and anxiety about crimes and their prevalence.

The problem is that we are notoriously bad at being statisticians, especially for things that have emotional valence like crimes. One murder 10 miles away? An argument can be made that this will not change your perception of safety and of the prevalence of crimes in your community. But how about three murders, 10 burglaries, five armed robberies, nine carjackings, three assaults and an arson for good measure? If these crimes are close to your location, you can see them as rapid-fire notifications and view them on your phone at any time. All of them either rapid-fire notifications to your phone if they’re close enough or available for viewing on your phone at any time.

How many of these reports tangibly influenced your day? How safe do you think your community is? More likely than not, very few, if any, of the reports were pertinent to your day-to-day life, and your view on the state of your community is worse than before because your perception of crime rates and the overall safety of where you live is not objective. Even if crime is decreasing overall, our ability to evaluate this objectively amidst all of these notifications is limited. This can have consequences for politics, such as who people vote for, as well as economics in the form of perceived high-crime areas facing economic consequences, especially during downturns.

Could these live-reporting systems save people’s lives through awareness? Maybe. What is far more likely is that people will have another source of pessimism about their environment when such feelings are unwarranted, similar to the effects that mass media have had on our individual and collective psyches. We are morbidly curious creatures. Giving us greater information that promotes safety is important, but apps like Citizen and Nextdoor trade a smidgen of enhanced safety for a mountain of fear. Knowledge is power, but that power swings both ways.

The Thumbnail is licensed under Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 .