SCOTUS: Is the Supreme Court “fuct” when it comes to trademarks and free speech?

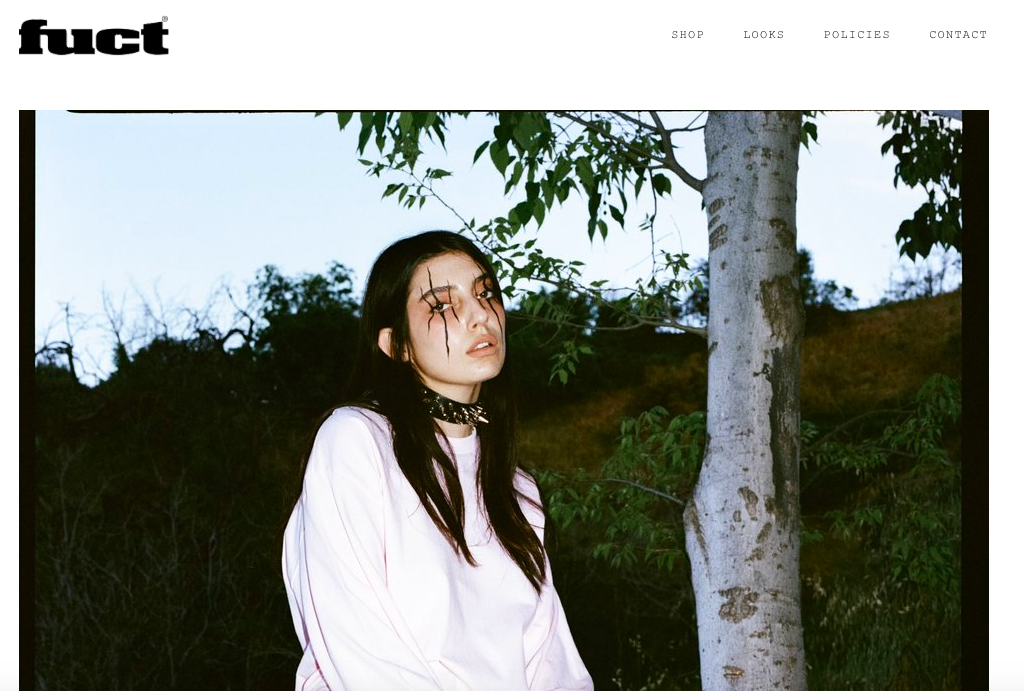

Erik Brunetti is the designer, artist and founder of the Los Angeles based clothing line “FUCT.” This streetwear line was the subject of the U. S. Supreme Court case, Iancu v. Brunetti, that was heard last Monday, Apr. 15.

The case first emerged when Brunetti challenged the refusal to grant the brand name trademark protection. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) denied trademark to the name because its pronunciation sounded like a “vulgar” word, therefore making it scandalous. The decision was reviewed by an attorney and is based on the Lanham Act that bars immoral or scandalous matter for patents in Section 2(a) of the Lanham Trademark Act.

Brunetti appealed the original denial to the Trademark Trial and Review Board, which upheld the original examining attorney’s decision to refuse the mark. Following that, Brunetti appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. The Federal Circuit Court ruled that the language of the Lanham Trademark Act was an unconstitutional restriction of freedom of speech in the First Amendment.

Andrei Iancu then appealed the Federal Court of Appeals ruling that sent the case to the U.S. Supreme Court. The primary concern the justices are addressing is whether Section 2(a) of the Lanham Trademark Act, which bars the federal trademarking of “immoral” or “scandalous” marks, violates the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment.

Another important case to consider in the context of Iancu v. Brunetti is that of Matal v. Tam, which was heard by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2017. This case involved the trademark registration of a band called “The Slants,” who said their name was reclaiming a racial slur used against minority groups. The PTO decided not to grant trademark protections based on the Disparage Clause of the Lanham Act, which states that trademarks shall not disparage against members of racial or ethnic groups. In an unanimous decision, the Court ruled that the clause was a violation of the Free Speech Clause because the vagueness of the clause led to viewpoint discrimination (restriction speech on a given subject). Chief Justice John Roberts concurred with his opinion that trademarking is not speech the government can regulate.

Tonja Jacobi, a law professor at Northwestern Pritzker School of Law, was surprised that after the Tam case, the U.S. Supreme Court took Iancu v. Brunetti because of their similarities. She explained that in her opinion, the justices have already decided this issue in the Tam case.

“They could have written Tam in a way that carved out an exception for the way it was being used [in the case], in that sort of ironic, reclaiming for the traditionally victimized group to use the slur themselves,” Jacobi said. “But [the justices] didn’t do that. They took a very strong position and now they sort of have to face the consequences of that and they seem reluctant to do so.”

Still, the issue of the Free Speech Clause and trademarks is being re-addressed by the Court. Now they are faced with either sticking to their precedent or creating a new definition of scandalous and immoral.

“The notion of being scandalous or immoral is just unconstitutionally vague. [...] They seem to be so open to interpretation and discretion; what is scandalous to you is not scandalous to me. So to have [trademark] benefits depend on that judgement is arguably unconstitutional because it is so unclear,” Jacobi expressed.

During oral argument, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg noted that 20-year-olds, the age range toward which the company was marketed, would likely find the name mainstream rather than scandalous.

Arguments in favor of the petitioner include the idea that a trademark is meant to afford government protections, such as the ability to advertise and sell commercially. The justices’ main critiques were that Brunetti could still sell his brand without the federal registered trademark without the “benefit of the government's participation in promotion of vulgarity,” according to Chief Justice John Roberts.

The contrary concern with this case involves use of the words “offensive” and “scandalous” and their subjectivity. The precedent this case could set is the restriction of speech based on someone’s personal viewpoint rather than objectivity.

According to Jacobi, another effect is the broad impact this ruling could have on what the government can and cannot regulate.

“If [the justices] rule in this case that the government can be making assessments of what is immoral or scandalous, does that have the same sort of impact for, for example, the FCC (Federal Communications Commission), saying what can be on television at a certain time? There might be broader implications,” Jacobi said.

Info gathered from oral arguments:

The attorney’s for the petitioners of the Supreme Court case, Iancu’s side, delivered oral arguments first. The attorney, Malcolm Stewart, argued that the Lanham Act was not an infringement of the Free Speech Clause because the scandalous marks provision is a content based criteria for trademarking. The petitioners asked for a narrow definition of the statute that is: “offensive, shocking to a substantial segment of the public because of their mode of expression, independent of any views that they may express.”

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg then asked who was to be the judge of shocking or offensive—she used the example that 20-year-olds, who the company was marketed towards, would likely not find the name scandalous but instead mainstream; Stewart claimed that the PTO were accurate in their statement that the general public would find the company’s name to be scandalous. However Justice Sonia Sotomayor said that the terms “shocking” and “offensive” imply subjectivity and a viewpoint, rather than using a measure like “obscene” or “profane” which are objective in society. Stewart argued that even words that phonetically sound like a profane word would be considered scandalous by a rational person.

Lawyer John Sommer represented Brunetti to the Court and argued that if the review of the trademarks are based in viewpoint, then it is subjective and therefore the statute is overboard. Sommer even notes that the PTO could still ruled out patents for obscene words because because Section 1 of the act requires trademarks to be viable for commerce which excludes profanity at a high standard.

Justice Stephen Breyer voiced concern that ruling in the favor of the respondents could set the precedent for racial slurs to be trademarked, which is inherently government association, and then advertised in public areas. Justice Neil Gorsuch asked why shouldn’t the government and people be able to decide that certain words are profane and as a matter of civility, people would like to see less of those words.

Funny enough, the word “fuct” was never uttered once in the courtroom, and was instead danced around by attorneys and justices alike through phrases such as “paradigmatic profane word.”