The death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, 87, on Sept. 18 left the United States with big shoes to fill in the Supreme Court. A week after her passing, President Donald Trump nominated Judge Amy Coney Barrett to the United States Supreme Court after much pushback from Democrats. The nomination is controversial for many reasons, one of which being Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s eagerness to confirm the nominee, which contradicts his actions in 2016.

At the crux of a presidential election, this empty seat on the Supreme Court bench adds more stakes to the election and more questions for the general public. If you're confused, don’t worry. Here are the answers to all of your questions.

Mitch McConnell and SCOTUS nominations, in brief

In February 2016, Justice Antonin Scalia passed away — nine months before the presidential election. President Barack Obama nominated federal appeals court judge Merrick Garland to replace Scalia a month later. However, McConnell announced that he would block any nomination to the court that Obama provided, arguing the next Supreme Court justice should be chosen by the next president.

Now, four years later, we are now presented with a nearly identical situation. Nevertheless, McConnell is currently supporting President Trump's nomination of Amy Coney Barrett, even with a more immediate proximity to the election than in 2016. McConnell explains to CNN that this sharp contrast is because the Senate and White House are occupied by the same party.

How do nominations to the Supreme Court work?

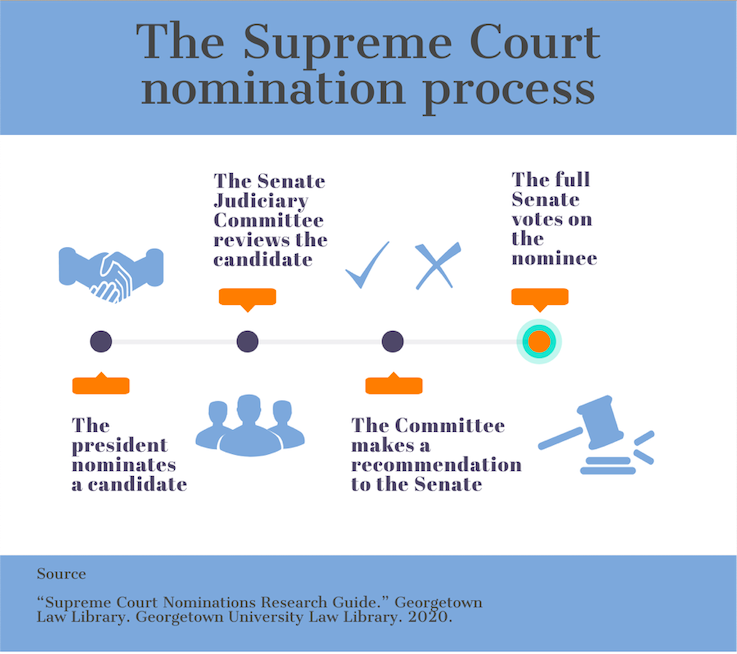

Article II of the U.S. Constitution states that the presidents "shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint [...] Judges of the Supreme Court [...].” When there is a vacancy on the bench, the president will consult with Senators regarding a list of nominees before announcing, although this step is more of a formality than a requirement.

After the nomination is announced, the Senate Judiciary Committee will hold a hearing for the nominee. To prepare, they collect all necessary records about the nominee from the FBI and other sources. At the hearing, witnesses will be called to present their opinions either for or against the nominee. Then, the nominee will be questioned by the Committee about their philosophies, judgement and qualifications. The Committee will then vote on the nominee and send the recommendation to the full Senate if it passes.

Next, the full Senate will debate the nominee. If a filibuster occurs — which means unlimited debate is allowed — a super majority (tw0-thirds of the Senate) is usually needed to end the debate. But in 2017, for Justice Neal Gorsuch’s nomination, the “nuclear option” was invoked, meaning that now, only a simple majority, 51 votes, is needed to end the filibuster. After the debate ends, the Senate votes on the nominee. If there is a tie, the Vice President votes.

Court packing: what is it?

Since Article II of The Constitution does not outline how many justices sit on the Supreme Court, it is in Congress's power to add more seats to the bench — i.e. “court-packing.” The idea is commonly associated with President Franklin D. Roosevelt who proposed expanding the Court to 15 justices in order to ensure the passage of his New Deal.

Proponents for packing the court see it as either a defensive move against their opposition or as a power-grab.

“I doubt many people have very strong positions about the proper size of the court that are entirely separate from their thoughts about the decisions that might result,” Joanna Grisinger, Director and Professor of Legal Studies at Northwestern University, said in an email. “But everyone can probably agree that it’s wise to have an odd number of justices.”

Most often, court packing is associated with the Democratic Party. For example, in a call from Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer to his caucus, he said that “nothing is off the table” if McConnell moves forward with replacing Ginsburg.

South Bend mayor Pete Buttigieg floated the idea of expanding the court during his race for the Democratic presidential nominee as a way to make the court less partisan.

Justices serve for life

Another idea that is often tossed around is that of term limits on Supreme Court justices. Currently, justices serve a life tenure that can sometimes last upwards of 30 years (Justice William O. Douglas is the longest serving justice, lasting 37 years). Supporters of term limits argue that it will depoliticize the court and even out the judicial influence of presidents. Opponents of term limits think the lifetime appointments important to serving the country rather than serving a president.

“If the idea is to make nominations less politicized, I’m not sure this would do it,” Grisinger said in an email. “It would make them politicized in a different way, and on a more predictable timeline, but is that better? I don’t know.”

Lifetime appointments can allow justices to choose when they retire, specifically, by waiting for a President sympathetic to their ideology or hand picking a successor. And in many cases, it leaves justices on the bench who are, arguably, mentally or physically unable to be there.

Regardless of opinions on the topic, it remains unclear whether or not term limits are constitutional. Article III gives Congress the power to regulate the Court, but it also says that justices will serve during “good behavior.” This has largely been interpreted to mean a life tenure, so scholars are divided over whether Congress can limit that tenure through legislation alone.

As Barrett’s nomination process is set to begin and the 2020 Presidential election is about a month away, there is much to look out for on the Supreme Court bench in the coming months.