Medill third-year and SteadyScrib co-founder Izzy Mokotoff’s grandfather has always been an avid writer. Writing is ingrained in his life: He’s authored everything from journalistic pieces to the handwritten letters he sends his grandchildren every week.

“About a year ago, he lost the ability to write the letters [to his grandchildren],” Mokotoff says. “He was typing them for a while, just because his Parkinson’s symptoms had advanced to a debilitating stage.”

When they met, Mokotoff and Alexis Chan, McCormick third-year and eventual co-founder of SteadyScrib, were neighbors in their sorority house. One night, Mokotoff shared her grandfather’s story with Chan and the pair discussed potential solutions.

“Then [Mokotoff] comes back a few days later and was like, ‘Just so you know, I had so much fun talking to you and brainstorming. Do you want to make this a reality?’” Chan says.

That’s how they formed SteadyScrib, which aims to create the first manual writing tool designed specifically for people with Parkinson’s disease.

Bringing ideas to life is what The Garage’s summer pre-accelerator program, Jumpstart, is all about. The Garage, located on the second floor of the Henry Crown Sports Pavilion, nurtures Northwestern students’ entrepreneurial pursuits with a special focus on initiative and community. It oversees 10 programs, including Jumpstart, throughout the year for Northwestern students interested in entrepreneurship.

In the span of 10 weeks, Jumpstart provides mentorship, workshops and a stipend to support teams’ ventures. To apply for the program, teams must present an idea and have at least two members. Each team’s work culminates at Demo Day, where students pitch their ventures to a panel of judges for a chance to receive funding in addition to the $10,000 teams receive throughout the summer.

“We had everything from a musical instrument video game that [you play by rehearsing] your instrument, to a device for patients with Parkinson’s disease, to software that helps math teachers grade and give feedback to math students,” says Mike Raab, executive director of The Garage.

Nine teams participated this past summer, including SteadyScrib, which placed first at Demo Day and took home the $4,000 first place prize as well as the $1,000 given to the audience favorite. Second place’s $3,000 prize went to academic feedback program Renota, and third place’s $2,000 prize went to gaming venture Overture Games.

According to Raab, Jumpstart students valued the wide variety of startups and came to depend on one another for advice and resources.

“A lot of the hurdles that student teams will face, others have faced before them,” he says.

SteadyScrib co-founders Izzy Mokotoff and Alexis Chan brainstorming at their workstation in The Garage. (Photo by Izzy Mokotoff)

Figuring out how to turn a late-night conversation into a working product was a journey full of hurdles for SteadyScrib. Mokotoff and Chan worked tirelessly to create a product that would help people living with Parkinson’s disease write with ease again.

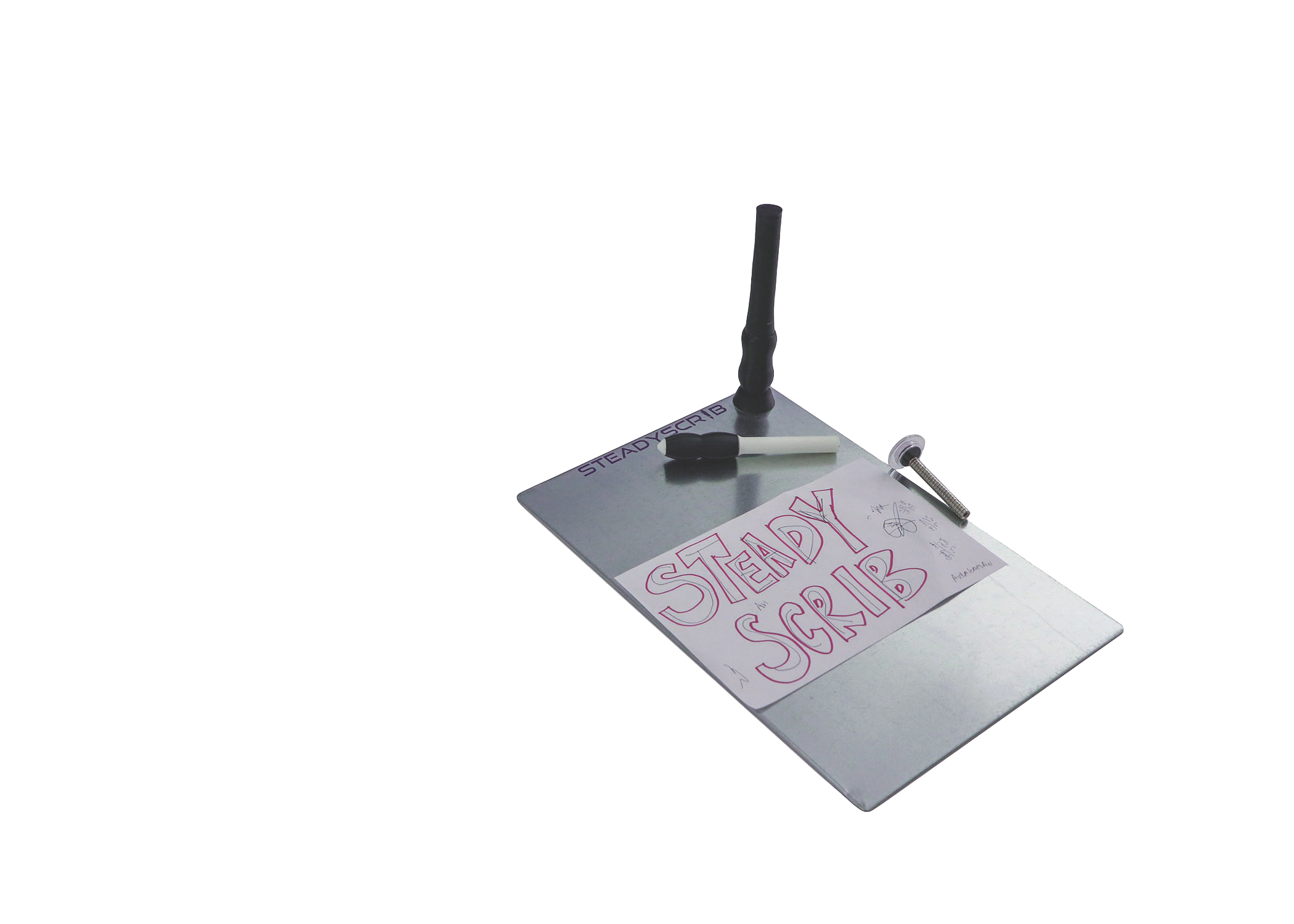

The current product design has two parts: a magnetic pen with a wide, pliable grip and a metal clipboard. When individuals write on a sheet of paper using the clipboard, the magnetic pen latches to the clipboard underneath it. The strong attraction between the pen and the clipboard stabilizes the person’s hand, allowing them to write comfortably.

Chan’s first attempt at making the pen using a 3D printer resulted in a pen far too large for anyone to practically use. Her second build attempt went even worse: Instead of anything resembling a pen, the printer spit out a mess of spirals. In Jumpstart’s 10 weeks, Chan and Mokotoff developed and tested 10 different pen designs. /p>

“I’m gonna be honest, at the beginning, I didn’t really know where to start,” Chan says. “But I kind of just thought, ‘Well, we have to start somewhere.’”

Chan says each day was full of trial and error, but after around six months and the first six weeks of Jumpstart, she arrived at their current design. Unfortunately, the pair lacked one crucial puzzle piece in order to start receiving feedback from people living with Parkinson’s.

SteadyScrib's most recent product model. (Photo by Izzy Mokotoff)

“We didn’t have enough money to pay a lawyer to write a patent,” Mokotoff says. “So Alexis and I wrote our own patent. We’re both undergraduate students, so obviously neither of us have a legal background.”

With advice from their Jumpstart mentor Casey Grace, founder of neurological device startup Hubly Surgical, along with existing patents on Google, the two third-years wrote their own provisional patent application. This type of patent establishes a priority date for their product, meaning that if someone else were to make a product identical to theirs, Mokotoff and Chan would be awarded rights to the design over any future inventors. An attorney edited and filed the patent for a fraction of what the original cost would have been if they had paid a lawyer to do so.

Finally equipped with legal rights, Mokotoff and Chan could receive professional feedback. They partnered with Northwestern Medicine and Movement Revolution, a non-contact boxing program that specializes in neurological conditions. Twenty different individuals with Parkinson’s disease gave them verbal feedback on SteadyScrib, and 15 of the 20 preferred SteadyScrib’s product over a similar pen designed for general aging.

“It was exciting to see people being excited about our pen and physical therapists asking to keep our pen at locations for further physical and occupational, therapeutic use,” Mokotoff says.

Using the funding they received from winning Demo Day, SteadyScrib is now focusing on finalizing a non-provisional patent application, which requires the formal approval of the United States Patent and Trademark Office. They also want to find a way to decrease their cost of production and examine all possible pathways into the market.

In light of their recent progress, Mokotoff and Chan say their core values always circle back to the man who inspired them in the first place: Mokotoff’s grandfather. At the time of her interview, she had just received a special package.

“I just got my one [letter] for this week. I read it this morning,” Mokotoff says. “The best part of this whole process is being able to watch my grandpa write again.”

Jake Erichson is a second-year graduate student in Kellogg’s Multidisciplinary MBA/MS Design Innovation Program and the founder of Renota, an academic feedback program. The concept behind Renota first came to Erichson while he was an undergraduate teaching assistant (TA) during his undergraduate years.

As a TA, Erichson spent around 8-10 hours a week grading problem sets. He says the feedback he provided was valuable for student’s development, but it took him too long to identify the issues in understanding and to consolidate edits. Renota takes on this repetitive task by catching small mistakes that math teachers would spend hours individually correcting, like a plus sign that should have a minus or simple arithmetic errors. Teachers can then focus their time on addressing more substantial errors that target conceptual misunderstandings.

The product also incorporates an online learning management program similar to Canvas or Blackboard. Teachers can create classes and assignments for students to upload work. The product’s software automates individualized feedback on each assignment, substantially reducing teacher workload.

“Ninety percent of my time was just figuring out what they did wrong. It was all procedural,” Erichson says. “Why is there a plus sign here? Why is this a six and not a 12? That took so much time and felt like something that a computer could be able to do.”

Erichson first identified this issue while in college, but he didn’t start toying around with potential solutions until after graduation. He worked in consulting for a few years and set the problem aside. When he came to Kellogg for graduate school, he says the academic environment resurfaced old memories.

When Erichson learned about Jumpstart, he saw the opportunity to fully dedicate himself to pursuing the concrete objectives for the software he had dreamed up years prior.

“We want our software to understand what the student is writing and point out where they’re going wrong,” Erichson says. “Then [it should] give the students some of that immediate feedback and give the teacher a snapshot of ‘Hey, here’s where your students and your class overall are struggling.’”

But Renota can only be successful if classrooms are willing to give it a shot. Erichson says the software’s greatest challenge over Jumpstart’s ten weeks was finding schools that would be willing to pay for a trial in the fall.

“In schools, it’s really challenging to get through the budget process and approval. There’s a lot of steps that you have to walk through before you get there,” Erichson says. “It’s heartbreaking when, you know, this is my baby.”

Despite the team’s struggles this past summer, Renota was able to tout a few victories. This fall, Renota will be implemented in two area schools, Evanston Township High School and North Shore Country Day School. Three teachers at each school will be implementing the program, so the trial group will consist of six different classrooms in total.

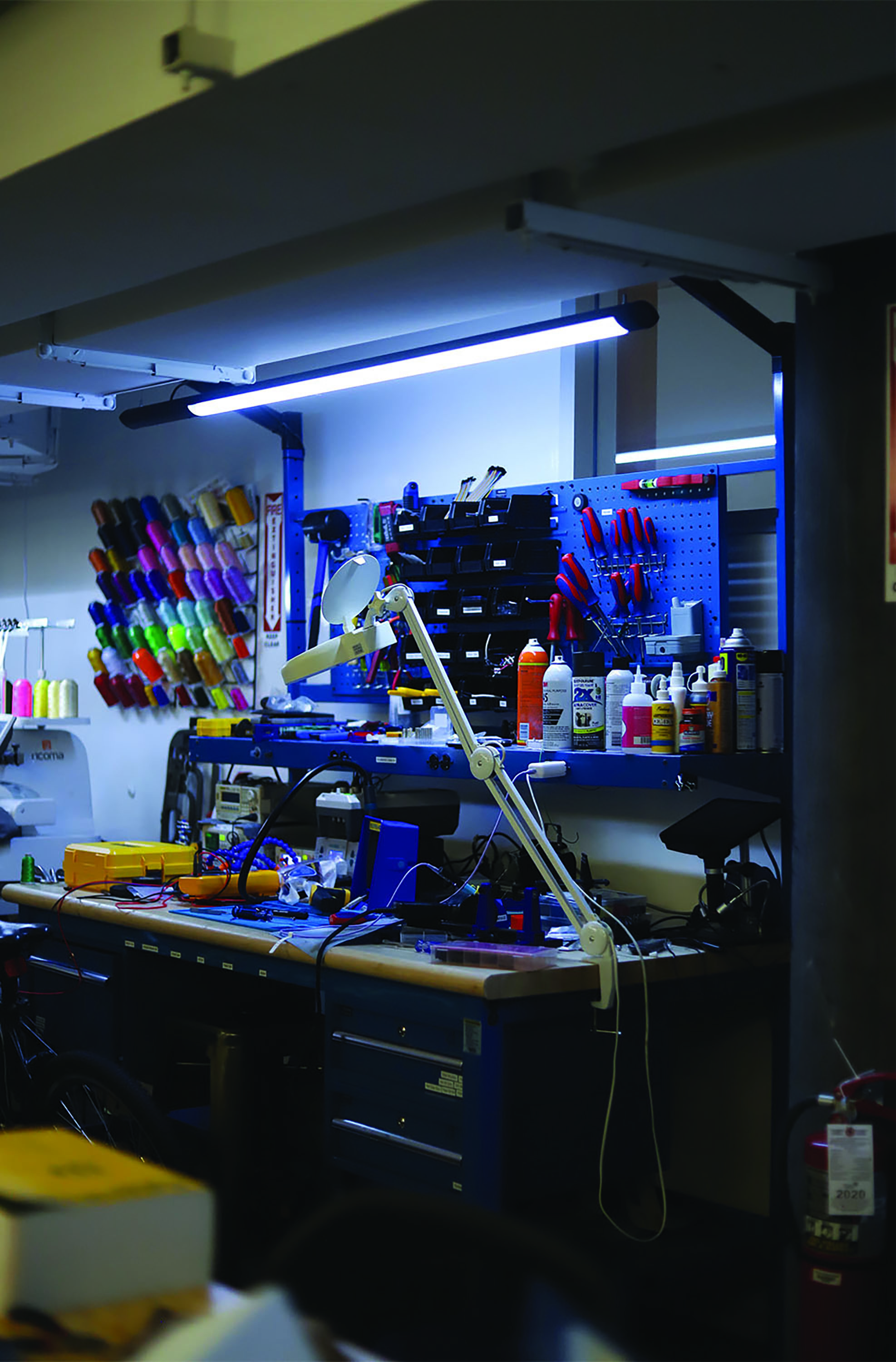

A communal workstation available to Garage residents as they develop their ideas and products. (Photo by Eloise Apple)

Despite being a fourth-year Bienen School of Music student, Aspen Buckingham says he hasn’t practiced piano seriously for a year. Years of practicing and coursework as a music major inevitably resulted in Buckingham feeling burnt out.

As a result, he became interested in games. Buckingham started attending game jams hosted by the game development community at Northwestern. At these events, participants have a few hours to create a game of their own. At one game jam, he met McCormick third-year Erin Park.

“I developed some games that I could play that got me excited to practice again,” Buckingham says. “I was talking to Erin, and I’m like, ‘Do you want to make this game that combines music, games and technology?’”

That’s how the concept behind Intervallic, Overture Games’ musical instrument practice game, was born.

One day, Buckingham says he remembers overhearing an intriguing conversation between Weinberg third-year Steven Jiang and another student at The Garage.

“I overheard him talking to another student wanting to make this app that helps music students practice their instruments, that helps them get more focused and excited about playing music,” Buckingham says. “I realized, ‘Oh, my gosh, Steven wants to solve the exact same problem.’”

Overture Games working on game development at their assigned table in The Garage. (Photo by Eloise Apple)

The trio set out to create their own game where the main objective is for students to have fun with their music rather than just learning it. They researched the competition: Some games were too costly, others were too boring and the rest focused on teaching beginners how to play the piece rather than intensive practice for musicians. None focused on the joy derived from playing music.

Buckingham, Jiang and Park conducted over 100 interviews with parents, teachers and middle and high school students about what they look for in a game. Buckingham says student interests drove their product development, even if this meant starting from scratch.

“We got about three weeks in, and we realized, ‘Oh my goodness, we are making a game that no one is really looking for. They’re actually looking for something completely different,’” Buckingham says.

Overture Games’ research culminated in Intervallic, a game where musicians can practice their pieces with a MIDI keyboard, a piano-style keyboard connected to a computer. Imagine a game like Subway Surfers or Temple Run where the player moves their character on screen to avoid obstacles and collect coins. The frustration of only making it so far and having to start over makes these games addicting. Depending on how accurately users play their pieces, the character can move farther along and collect coins, incentivizing playing and ultimately practicing.

Jiang, chief strategy officer of Overture Games, says everyone is on board to work on the startup full-time.

“We do want to work on this venture after we graduate,” Jiang says. “I think the whole team is trying our best to make that happen.”

Overture Games’ MIDI keyboard that players use to navigate Intervallic. (Photo by Eloise Apple)