How Northwestern’s female engineers are working to close the industry gender gap.

When Molly Dudas first walked into her internship with an engineering design company, she was shocked to see the 79 other interns. Except for one of the two directors, she was the only woman in the design studio. Later, when Dudas was chatting with the directors, they told her that they would have loved to include more women in the program, but they only received three applications.

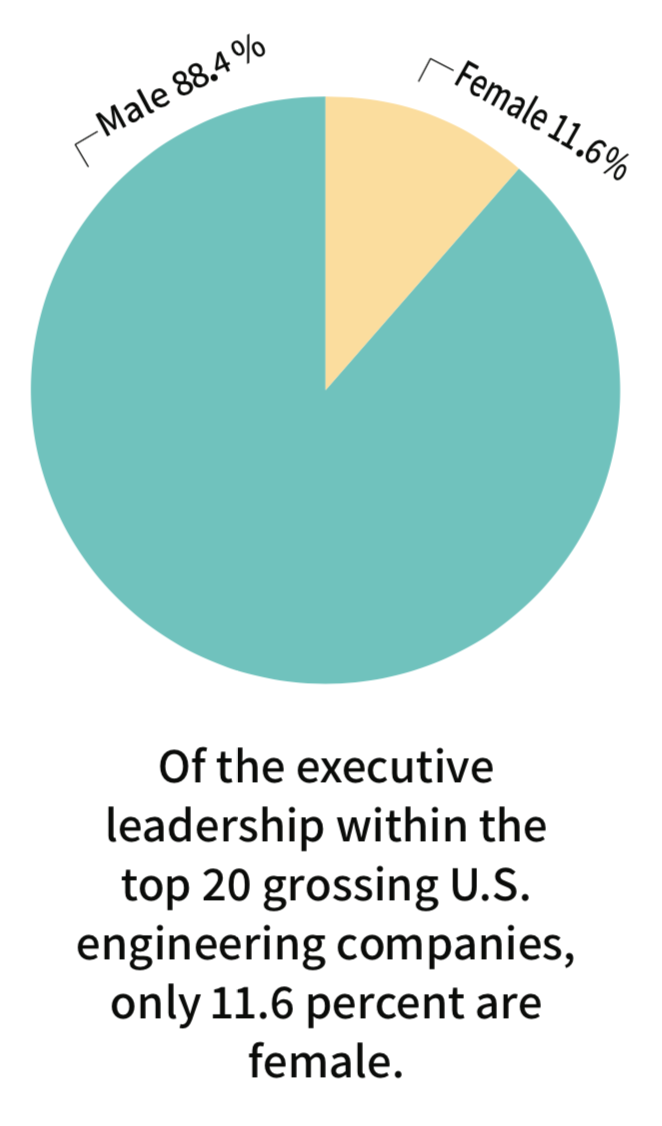

Though Dudas was frustrated by the lack of women engineers, she at least felt hopeful because one of the directors was female. Of the executive leadership within the top 20 grossing U.S. engineering companies, only 11.6 percent are female. Many of those women hold positions not directly related to engineering, such as ethics and compliance officer or marketing and communications director. And this trend begins long before reaching the top of the corporate ladder: like many schools, Northwestern has few women engineering students and even fewer in leadership positions.

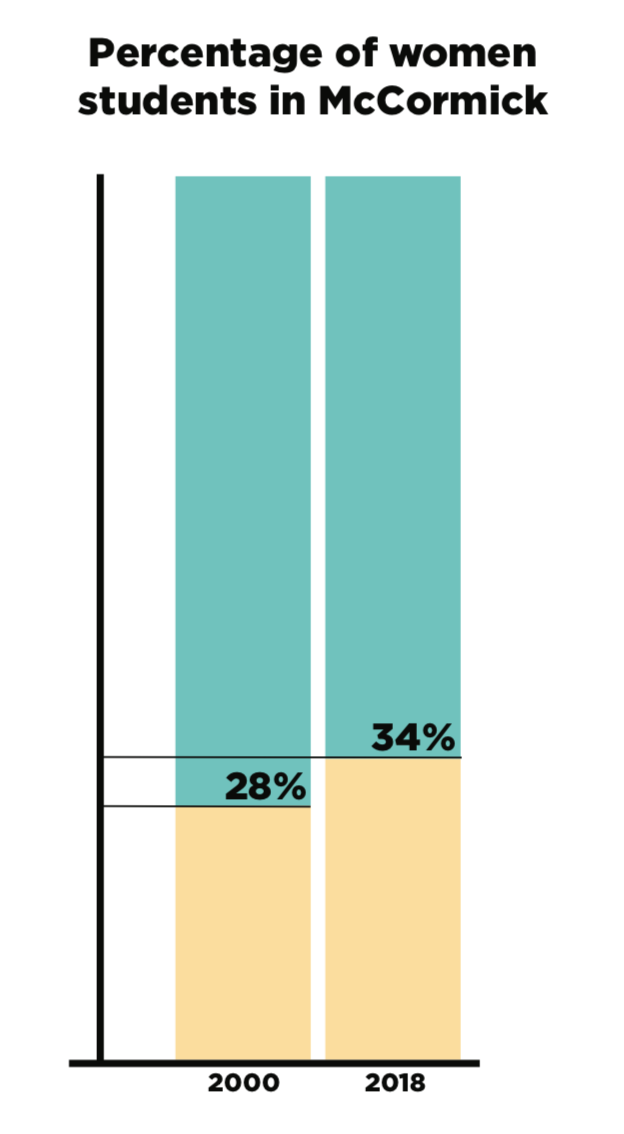

Ellen Worsdall, McCormick’s assistant dean of student affairs, says that when she first came to Northwestern 19 years ago, her job was to increase the number of students from underrepresented backgrounds in McCormick and to improve their experience. Around 28 percent of students were women — a number considered relatively high at the time. By 2018, this number had increased marginally to 34 percent. Worsdall points out that McCormick’s gender proportions match the numbers at many of Northwestern’s peer institutions, like Johns Hopkins’ Whiting School of Engineering, which is about 27 percent female.

Representation may have improved, but it’s still not equal. Inequality pervades the experiences of many female engineers, like Dudas, who joined the Society for Women Engineers (SWE) to address this phenomenon. She eventually became the director of HeforSWE, a program that educates men and engages them in the conversation about gender discrimination. The main mission of HeforSWE is to train male advocates to feel more responsible for their own behavior, as well as their colleagues’.

Most students know how to recognize outright sexism in the classroom and workplace. However, much of the sexism in STEM is more insidious. Jacqueline Vega, the president of the Society of Hispanic Professional Engineers (SHPE), knows about this kind of sexism: the kind that builds up over time, erodes your confidence and makes you question your abilities and convictions.

“I’ve had teachers who have actually told me, ‘Oh, maybe you should reconsider engineering. Your grades are on the lower end of the scale,’” Vega says. “This is what I want to do. I was just trying to ask for help.”

Vega wondered whether these teachers would have said the same thing to her male peers. Weathering the constant storm of disapproval is tiresome and frustrating, and not all women make it out to the other side. Several female engineers at a SWE event described it as “death by a thousand cuts.”

While Dudas estimates that 30 to 40 percent of executive boards of STEM clubs are female at Northwestern, the number of female presidents of engineering clubs gave her a rude awakening.

While attempting to organize a focus group of men leading engineering clubs for HeforSWE, Dudas realized that almost all of the clubs she looked at had male presidents. At a HeforSWE workshop, participants noted that women often hold positions like social or philanthropy chair, sitting in the background with more stereotypically “female” roles while men stand at the front as president or project manager.

To name a few, Northwestern’s chapters of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, Baja SAE (a club that builds small offroad vehicles), the Biomedical Engineering Society, the Neuro Club, NU Robotics, NUSTARS, Formula Racing and more all have male presidents.

Alice Eagly, a Northwestern psychology professor who has written numerous publications about women in leadership positions, stressed the importance of getting leadership experiences, especially in college. So, why aren’t there more women engineers in leadership positions at Northwestern?

Simply put, there are fewer women to fill leadership positions in the first place. There are also few female faculty members in McCormick, though this is the norm among engineering schools. Worsdall provided the same reasoning for the small number of female student leaders as faculty.

“You don’t ever want to hire someone just because they fit into a box, right?” Worsdall says. “The pool for female faculty is smaller than that for male faculty. And so we have to do more to change the pool.”

For this reason, Worsdall runs programs to increase the number of women entering engineering in the first place. According to Worsdall, Northwestern has worked hard to grow its female engineering base and is happy with its progress.

For this reason, Worsdall runs programs to increase the number of women entering engineering in the first place. According to Worsdall, Northwestern has worked hard to grow its female engineering base and is happy with its progress.

“We’ve made changes to the programs because of insight from students or suggestions from students, but basically the bones of the programs were created long before I came,” says Worsdall.

Worsdall is in it for the long game; progress has been ongoing but slow. Societal influences discourage women from entering engineering, Worsdall says, which are hard to change in just one generation.

“I think there’s all these subtle messages if you’re a female that maybe you should look at something else. Maybe you should work with people more,” Worsdall says. “Your gender does not give you an advantage using a calculator. If you look at AP high school physics classes and calculus classes, we still have students who talked about how there were only two girls in their physics class.”

Worsdall says that the only way to fight these influences is to support young women early through programs that shift them away from an anti-math perspective. Now, some of the students Worsdall reached out to early in her career are enrolled in Masters and PhD programs. Worsdall proudly displays on her filing cabinet the graduation announcement of one student whom she mentored as a sixth-grader.

In McCormick, the retention rate of female students is actually higher than that of male students. Ninety-three percent of female students stick with engineering, compared to 87 percent of male students. Worsdall attributes the healthy retention rate to a growing support and mentorship system for female students. Comparatively, according to SWE, over 32 percent of women switch out of STEM degree programs in colleges across the country. This number is staggering considering that fewer women are admitted into STEM programs in the first place.

Despite low enrollment statistics and stifling stereotypes, Dudas remains hopeful that programs like HeforSWE can do some good. HeforSWE programming inspires her and fuels her desire to keep going in the industry. Even if it’s slow, the field of engineering is changing and executives are becoming more sensitive to the challenges women face in engineering and other similarly male-dominated fields, Dudas says.

Despite low enrollment statistics and stifling stereotypes, Dudas remains hopeful that programs like HeforSWE can do some good. HeforSWE programming inspires her and fuels her desire to keep going in the industry. Even if it’s slow, the field of engineering is changing and executives are becoming more sensitive to the challenges women face in engineering and other similarly male-dominated fields, Dudas says.

Dudas remembers one speaker at a SWE event who discussed a specific time when she didn’t have to stand up for herself. When the speaker worked in a cooperative education program, an indirect superior cut her off and spoke to her rudely at a board meeting; she felt like she couldn’t say anything. A fellow male intern told their boss, who, at the next meeting, told the man to apologize to her. The relief she felt that she wouldn’t have to confront him herself or, worse, deal with further disrespect, was palpable.

“We’re trying to promote stuff like that,” Dudas says. “Not that we can’t stand for ourselves. But why should we always have to?”