Content warning: This article discusses instances of homophobia.

Weinberg third-year Jordan Vaughn sat at a table in Deering Library on a February morning, poring over a sizable collection of manila folders. She spread out papers advertising dances and protests, combed through a ledger with financial notes on a screening of The Rocky Horror Picture Show and read letters to school administration about the cost of HIV testing.

These documents came from the five-decade history of Rainbow Alliance, an organization that serves the needs of LGBTQ+ Northwestern students. Among the yellowing pages, Vaughn, Rainbow Alliance’s current internal president, saw the group's legacy of supporting and advocating for Northwestern's queer community.

“It’s so easy to take for granted what we have now,” Vaughn says. “I can’t imagine what it would’ve been like to be a queer person here in the '70s.”

Rainbow Alliance’s roots reach back to April 1970, when a group called Northwestern Gay Liberation sent a letter to the school’s faculty announcing its creation. According to the letter, the organization was founded to “actively oppose the oppression of homosexuals” by educating the heterosexual community about harmful stereotypes, pushing for equal rights and hosting social events for the gay community.

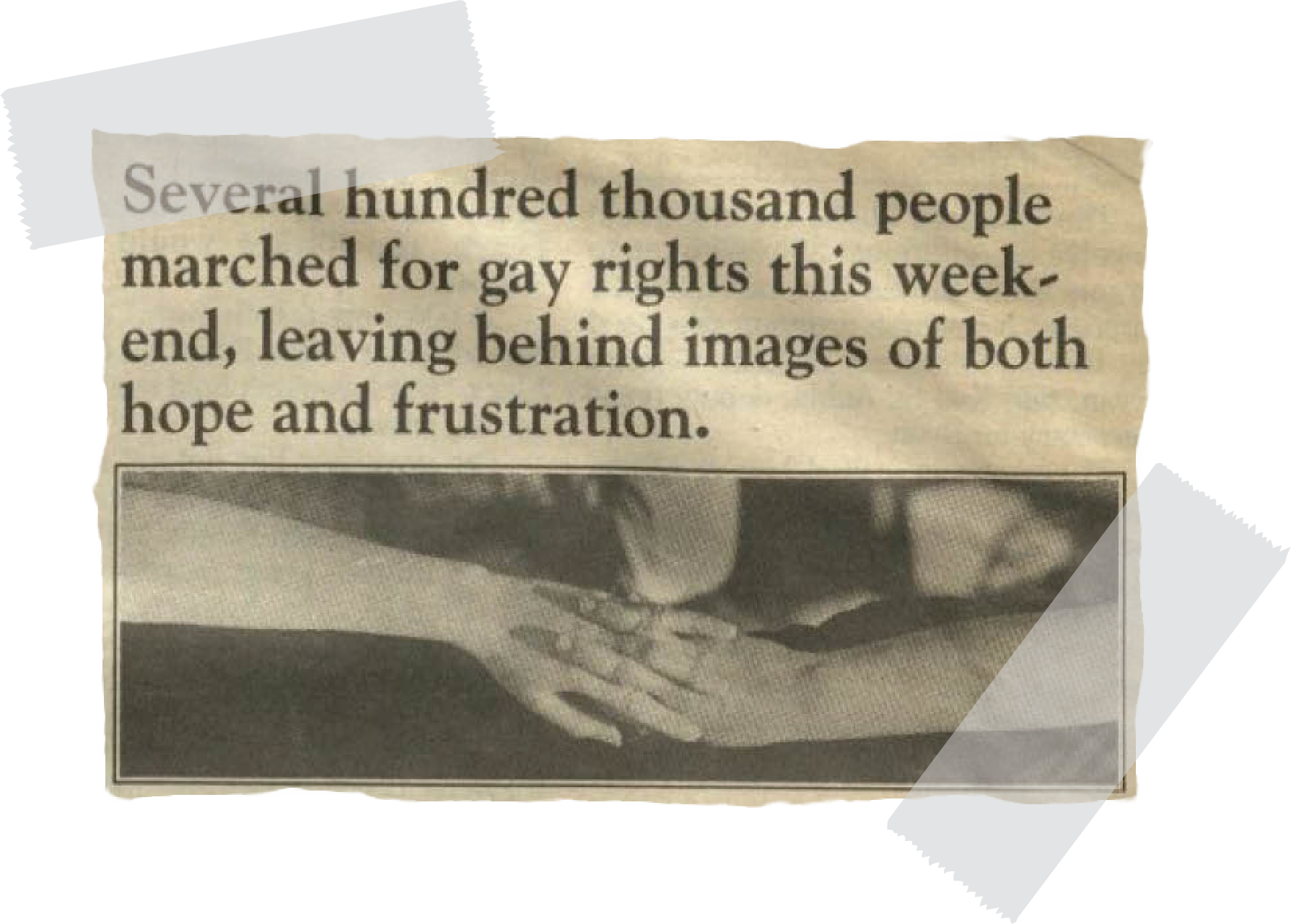

Gay Liberation’s first major initiative was a petition to Northwestern's then-chancellor asking the school to publicly denounce all discrimination against the gay community. In the organization’s early days, their advocacy initiatives were coupled with social events. According to University archives and reporting in Northwestern Magazine, Gay Liberation hosted a well-attended dance in Patten Gymnasium that featured a popular blues band.

The organization’s initial momentum faltered by 1981 due to a lack of funding and minimal structure. Renamed Gay And Lesbian Alliance (GALA), the group still existed, but with reduced visibility. In Spring Quarter 1981, Stuart Graff (McCormick ‘84), then a first-year, was walking on the Technological Institute’s front terrace when a woman handed him a pamphlet promoting a GALA-sponsored event. Though he couldn’t make the event, Graff went to a GALA meeting at an off-campus apartment during Fall Quarter 1982. After discovering the group lacked official leadership, Graff decided to take charge.

GALA started to sponsor a mix of social spaces and political work in the following years, with events like a teach-in dedicated to addressing the AIDS crisis through group discussions and a lecture from a faculty member. Graff says he knew people who were dying from the virus and wanted to spread awareness while fighting the harmful stereotypes around it. As a result of his work, Graff says he was called homophobic slurs during phone calls he received in the middle of the night.

“One way you assert your identity is not only claiming who you are but who and what you're not, and what you stand for and what you stand against,” Graff says.

GALA members recall that at the time the campus climate toward the LGBTQ+ community ranged from accepting to curious to blatantly homophobic. In 1992, The Daily Northwestern reported that a GALA member working the door at a Friday night dance said he was called a homophobic slur by a man who also tried to hit him in the face. That same year, Norris University Center was spray painted with the words “Die Queers, there will be blood.”

Graff says he did not let the homophobia he experienced make him angry. Instead, he continued to emphasize visibility for the school’s gay community, which he felt would combat hateful rhetoric and reduce stigma around being openly gay.

Graff remembers sitting at GALA’s table during a student activities fair in Fall Quarter 1981 when he saw a high school classmate who also attended Northwestern. The student was surprised and concerned to see him at the table. When he asked Graff what he was doing there, he told him he was running the organization. A few months later, the student returned to Graff and came out to him.

According to Graff, GALA's visibility was vital to changing the campus’ climate toward gay students from exclusion or mere “tolerance” to active acceptance.

“We're not here to be put up with. We needed to be accepted,” Graff says. “I think we got a lot of acceptance from people that didn't even know that we were there, let alone that they needed to accept us.”

In the following decades, the group changed its name to Bisexual, Gay And Lesbian Alliance (BGALA) and focused on providing a place for members to socialize. For Rebecca Dunne (Bienen ‘98), who came out during her first year at Northwestern, BGALA was her starting point in the queer community. She remembers the group’s annual drag show and regular off-campus brunches, as well as meetings in the Norris office that Rainbow Alliance still uses today.

While Dunne was the only woman in the group for much of the time she was involved, she says finding other gay students of any gender was the main benefit of being in BGALA.

“We all sort of clung to each other like, ‘Oh my god, you’re gay, I’m gay. It’s great,’ and that’s all we were thinking,” Dunne says.

BGALA adopted its present name, Rainbow Alliance, in 2002. When Communication third-year Jo Scaletty came to Northwestern from their hometown of Adrian, Missouri, they had never been in a formal environment where they felt comfortable being queer. Scaletty became Rainbow Alliance’s Associated Student Government (ASG) senator at the start of their second year. Through their senatorial work, they connected with LGBTQ+ students on campus while supporting the community’s needs.

Scaletty is now Rainbow Alliance’s external president and says the group is looking to reconnect with the activism of its past. Scaletty and Vaughn both say expanding access to gender-neutral bathrooms and housing options is a key objective for the group. They also want to focus on making Northwestern’s health system more accessible for gender fluid students.

“[Rainbow Alliance is] working to make sure that however queer students show up on campus, they show up with ease and with comfort and knowing that the system has been built so that they're okay in those spaces,” Scaletty says.

Socially, many of the group’s current events aim to make Rainbow Alliance more inclusive. Vaughn says the group used to place a heavier emphasis on forming a gay-straight alliance and was predominantly white. Many of its recent events have been spaces for students with intersecting identities to mingle, such as Black queer students and queer students with disabilities.

Vaughn says that Rainbow Alliance’s archive in Deering showed her the group’s path to establishing itself and creating space and support for LGBTQ+ students at Northwestern. She believes the present Rainbow Alliance can be inspired by the persistent spirit and justice-oriented work that characterized its previous forms.

“Rights and privileges were gained really slowly in the past, but [the group] was still constantly looking for improvement,” Vaughn says. “I think it would be important to embody that again.”