After five assault incidents on campus, Northwestern women act on heightened anxiety.

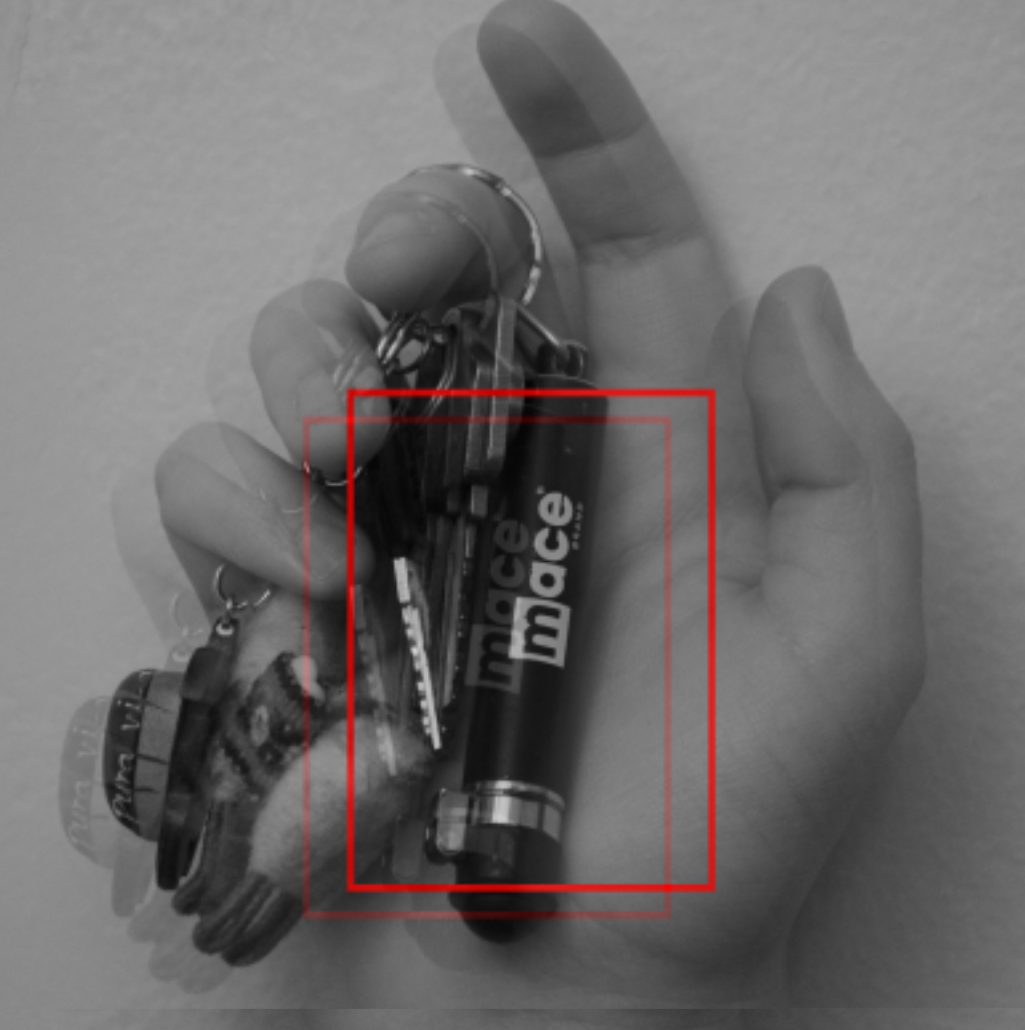

Personal alarms. Whistles. Pepper spray, batons, or keys, facing outward, between the knuckles. This is just a sampling of the equipment Northwestern students – particularly those who identify as female—are using to arm themselves after a total of five incidents of harassment, most involving grabbing, rocked campus fall quarter.

But more important than the self-protection strategies themselves is the psychological toll they represent. Regardless of what physical objects students are carrying, safety stress is an anxiety some aren’t putting down, even as the Northwestern University Police Department says that increased foot patrols and other tightened security measures have brought an end to the attempted grabbings.

When Kiana Jones steps off the shuttle, she has a block and a half to walk to her apartment. “Not that much,” the Weinberg junior says. But every couple seconds, every time she hears a sound, even if it’s her own footsteps, she looks to both sides. She will even do a complete 360, just to be sure that no one is approaching her from behind.

“It’s becoming habitual,” Kiana says. “I keep doing it. I keep doing it, picking up my pace a little bit, and I’m like, ‘Why am I acting like this?’” When she gets to her building, she enters a code and steps inside, shutting the door behind her quickly so it locks. “I go ‘Okay’ and I act like I didn’t just completely freak out outside.”

Kiana called the incidents of the fall a wake-up call. She says there was a stark difference in safety level between Evanston and the Chicago neighborhood where she grew up, Morgan Park. She says that the park nearest her house is notorious for shootings and fights. By contrast, Northwestern and surrounding Evanston felt comfortable, especially because her cousin had also been a student here. Until the incidents.

“I got nervous in the fall and very scared and I’m like, ‘I’m from Chicago,’” she says. “I wasn’t scared when my mom wouldn’t let me go to the park and I wasn’t scared when there was a shooting… why am I scared because of some wannabe kidnapper?”

After three years of feeling secure in her environment, the idea of people being assaulted is one Kiana can’t get out of her head. It’s the same for Camille Guzman, a McCormick sophomore who lives in Willard, adjacent to where some of the incidents occurred. She says that because of her proximity to the physical space where the grabbings occurred, safety is on her mind more than ever.

“Sometimes I would totally forget about what happened and be close to the sorority quad, and then I would remember and I’d be like ‘crap, I should be walking a lot faster,” she says.

Camille and her friends have a group chat where they sometimes ask if they can give one of the other members in the group a call so they can talk to someone until they reach the safety of home. She says that her male friends help out with this, but that they don’t fully understand the impact the incidents have had on her and her female friends.

“They did express concern or sympathy for us,” Camille says, “But they didn’t seem visibly worried at all because it wouldn’t affect them.”

According to Wesley Skogan, a Northwestern political science professor who specializes in crime and policing, women have always felt more vulnerable to victimization. “At any level of actual crime, any level of actual real risk, there’s very substantial difference between men and women.”

But the incidents last fall were a whole new level. The grabbings were more than another mundane marker of womanhood. Instead, they served as a pointed reminder that women are often targets, not just of harassment, but of physical, bodily harm.

On a cold and slushy Tuesday night, a group of 15 women assembled in a second floor room in Norris. Hot pink goodie bags were lined up on a table pushed against the wall to make room for the circle of women, who were laughing with their neighbors while they flung their fists through the air.

These women were learning how to punch, kick and claw their way out of danger during a self-defense class hosted by Victoria’s Secret PINK’s campus ambassadors called “GRL PWR.” While it was high on branded freebies and positive affirmations, the group was gathered for serious reasons.

Towards the end of the class, instructor Kayla Carter realized there wasn’t enough time left to talk about the three situations for which she had planned. She asked the group to vote: did they want to learn how to escape a choke, knife or grabbing situation? After some quiet murmuring, grabbing emerged as the victor. It felt like the most likely scenario the group would have to confront.

Kayla, a McCormick junior, always thought that learning self-defense was important for women, but after she heard about the third incident in the fall, she immediately scheduled a training for students living in Slivka, where she works.

“[I felt] angry and frustrated with the administration and the police,” she says. “It’s sad but even sadder when the people who are supposed to be protecting us aren’t being transparent.”

Part of the confusion over the fall centered around the fact that NUPD didn’t realize the events were connected until after the third incident. This was frustrating for a lot of students, who wanted as much information as possible, but Skogan says there are so many random incidents that it’s not always easy to discern a pattern with this kind of immediacy.

Part of the confusion over the fall centered around the fact that NUPD didn’t realize the events were connected until after the third incident. This was frustrating for a lot of students, who wanted as much information as possible, but Skogan says there are so many random incidents that it’s not always easy to discern a pattern with this kind of immediacy.

When it becomes clear that events are connected, “all of a sudden people have probably the realistic sense that the place that they’re at is being targeted.” This is much more frightening for people than the possibility of a random incident perpetrated by someone who will probably never be seen again, according to Skogan.

At the beginning of winter quarter, NUPD announced that the assaults had stopped because of new safety initiatives they spearheaded, in conjunction with the Evanston Police Department, as well as the foot and vehicular patrols they had stationed on the south end of campus, where the incidents took place. Still, not all students feel comfortable around NUPD.

“It wasn’t a question, it was more of a ‘this would definitely help,’ not realizing all of the population of students,” Kiana says, referring to increased police patrols. “It may be good for...white identifying students, but for black students, for Muslim students or any other identity it’s like…it actually made us go in the opposite direction of NUPD, which kind of defeats the point of having them there.”

Kiana is addressing the specter of police brutality, an omnipresent issue in the news media and a particularly poignant problem for a community in the shadow of Chicago, where policing practices were deemed unnecessarily aggressive by the federal government and where the Laquan McDonald case has been front of mind since 2014.

Kiana says she feels like the problem is that NUPD doesn’t seem to have relationships with students. Just seeing an NUPD officer doesn’t make her feel any safer. “They don’t speak at all,” she says. “I’ve walked past plenty of foot patrols, no acknowledgement no ‘Are you ok? How are you doing,’ nothing.”

Calls for stronger personal relationships between cops and the people they police are common in many communities, Skogan says. People want a certain level of familiarity with their police officers that breeds mutual respect and understanding. But for police departments, it’s a challenge of resources.

“The organization has to believe that establishing that kind of rapport is important and important to the other things they do,” Skogan says. “Because if they’re doing that they’re not doing something else—it’s a 100 percent tradeoff.”

NUPD went door to door in the area surrounding the location of the attacks to ask residents whether they would like to speak to officers about security planning and also hosted personal safety seminars in addition to the new safety initiatives, according to Deputy Chief of Police for NUPD Eric Chin.

Chin says that it is NUPD’s goal to be approachable for students. “We know that a lot of our student base comes from other areas and perhaps their relationship with their law enforcement agency isn’t quite the same as ours,” he says, “what we would like to be able to do is dissolve that perception for students that come in.”

Throwing kicks towards Kayla’s face during the self-defense class felt awkward. But as she came around the room holding up pads to practice with a real target, nearly every woman in the circle asked to take an extra turn.