In the intersection of reality TV and political governance lies California. A months-long trudge through an election-turned-entertainment-spectacle, the Newsom recall debacle has captured our peripheral attention for the past year. This Shakespearean political drama began, like all good stories, with a fancy dinner.

Among mumblings about Newsom’s leadership throughout the pandemic, Fox 11 released exclusive photos showing Newsom eating with his friends at The French Laundry. This fairly mundane event was the spark that lit the media wildfire. The funniest part is, that despite the constant attention, this is a story in which literally nothing happened: no governor was actually recalled, and, despite a lot of hullabaloo, nothing in the political realm changed.

California’s complex gubernatorial history

Because of California’s size, the governorship can seem like a presidency. California has a larger population than many smaller countries, and if it were its own country, it would rank as the fifth largest economy in the world. This often manifests in a focus on the governor as a head of state with a lot of responsibility for what happens under their purview. The increased scrutiny combines with a unique quirk of California law: simultaneous recall elections.

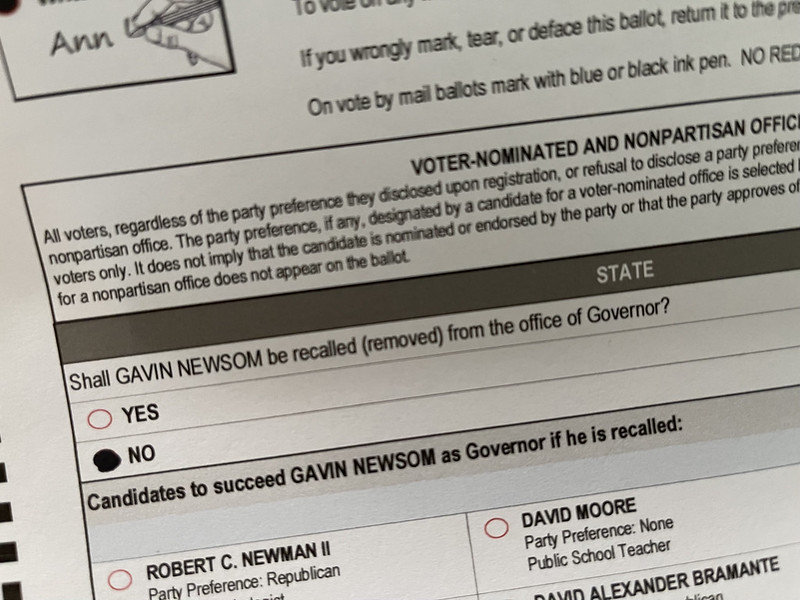

California has a special procedure shared with only six other states called a simultaneous recall election, meaning that with enough signatures, a special election can be triggered to replace a sitting governor. Then, as the National Committee of State Legislatures put it, “The first question is whether the official should be recalled. Voters are then asked to vote for a candidate for the office.”

The recall vote option has only been used once before, with the well-known election of Arnold Schwarzenegger, who succeeded Gray Davis as governor of California in 2003. Davis’ reputation was irredeemably trashed following massive budget deficits, an unpopular car tax and constant energy brownouts. And because of the increased focus on the office of the governor, the issues facing California were turned straight against him, sparking Davis’ loss in the special simultaneous recall election.

Newsom’s early recall

This was the exact process that Republicans had been wanting to use against Newsom for months and had pushed for well before Newsom’s later political scandals. But with the breaking of the Fox 11 photos, the movement for a recall began in full, quickly amassing the 1.5 million signatures needed to trigger the special election just five months later.

The recall vote gained a lot of notoriety, at both the state and national level, and things were looking good for those pushing for the recall at the start. Early polling from UC Berkeley showed that only 45% of voters opposed the recall – a statistic that “represents a big shift in public sentiment,” according to the same study from within this Democratic stronghold. Lots of candidates joined in hopes of succeeding Newsom, including Newsom’s former political rival John Cox, Olympian and reality TV star Caitlyn Jenner, and even Mary Carey, a former adult film star.

Despite all the candidates and media frenzy that followed this announcement, Larry Elder quickly emerged as the only viable candidate. A lawyer and former conservative radio pundit, Elder attempted to use the wave of antipathy against Newsom’s COVID policies to win the governorship. His core platform evolved into a Republican libertarian stance mixed with a lot of fighting against vaccine and mask mandates, plus opposing any and all business restrictions. Elder was a firm Trump supporter, calling his ascension to the presidency “divine intervention,” in an interview with CNN. However, he later shifted his focus away from Trump amid increasing controversies.

End of the line

As the recall movement gained more and more steam, the Democratic Party began to fight back against this growing threat. With 88-year-old Dianne Feinstein holding one of California's senator seats, a change in party control could literally flip the Senate, according to NPR’s analysis of the situation.

Democrats currently hold a narrow 50-50 control over the senate, with V.P. Kamala Harris breaking the tie in favor of Democrats. If Feinstein could no longer perform her job, the governor would oversee the appointment of a replacement – likely a Republican if Newsom were replaced. This would flip Senate control, making Mitch McConnell the de facto majority leader once again. This threat to their power awakened the National Democratic Party, who began to put their entire weight into saving Newsom – including public messages from Democrats to vote in the election and even a speech from President Joe Biden.

While prospects for the recall seemed somewhat positive at first, this was likely a mirage because the recall had no real opposition until they had alarmed Democrats sufficiently. Polls began to show that as early as August, the movement would most likely not succeed, with a SurveyUSA poll showing 51% of voters opposing the recall of Newsom. However, this did not stop Larry Elder, who continued pushing for the recall till the bitter end. Following Trump’s lead, before the results were even out, Elder declared the vote fraudulent.

Why does this recall matter?

It's a little strange that the movement to impeach a single governor made national news for nearly a full year. Why would the country care about this one man’s election when we have so many things to focus on and, again, literally nothing happened? Why care so much about just one state’s governor when, as a family member of one of the opposition candidates said, “Kim, there’s people that are dying.”

The election holds political implications that are relevant to the U.S. nationally. First of all, the election’s proximity to the Democrats' losing control of the Senate shows how tenuous Democratic control truly is. If a single election went wrong in one state, the entire Senate could have been flipped. Second, the ability for this recall movement to grow this large in one of the country’s most liberal strongholds is ominous. If California’s Republicans could gain such momentum, with nearly 60% support at one point, what could Republicans do in newly blue states like Arizona, Georgia or even Illinois?

And, finally, though Elder’s preemptive declaration of fraud may be funny, it serves as a grim reminder that Trump’s “Big Lie” conspiracy has become a ubiquitous part of the Republican playbook that we may begin to see at elections of all levels. As The Guardian pointed out, “the myth of a stolen American election has shifted from a fringe idea to one being embraced by the Republican party.”

Though Newsom survived the recall in the end, this humorous tale serves as a possible canary in a coal mine for the upcoming midterm elections and even the next presidential election.

*Article thumbnail "Gavin Newsom recall ballot" by Sarah Stierch is licensed under CC BY 2.0.