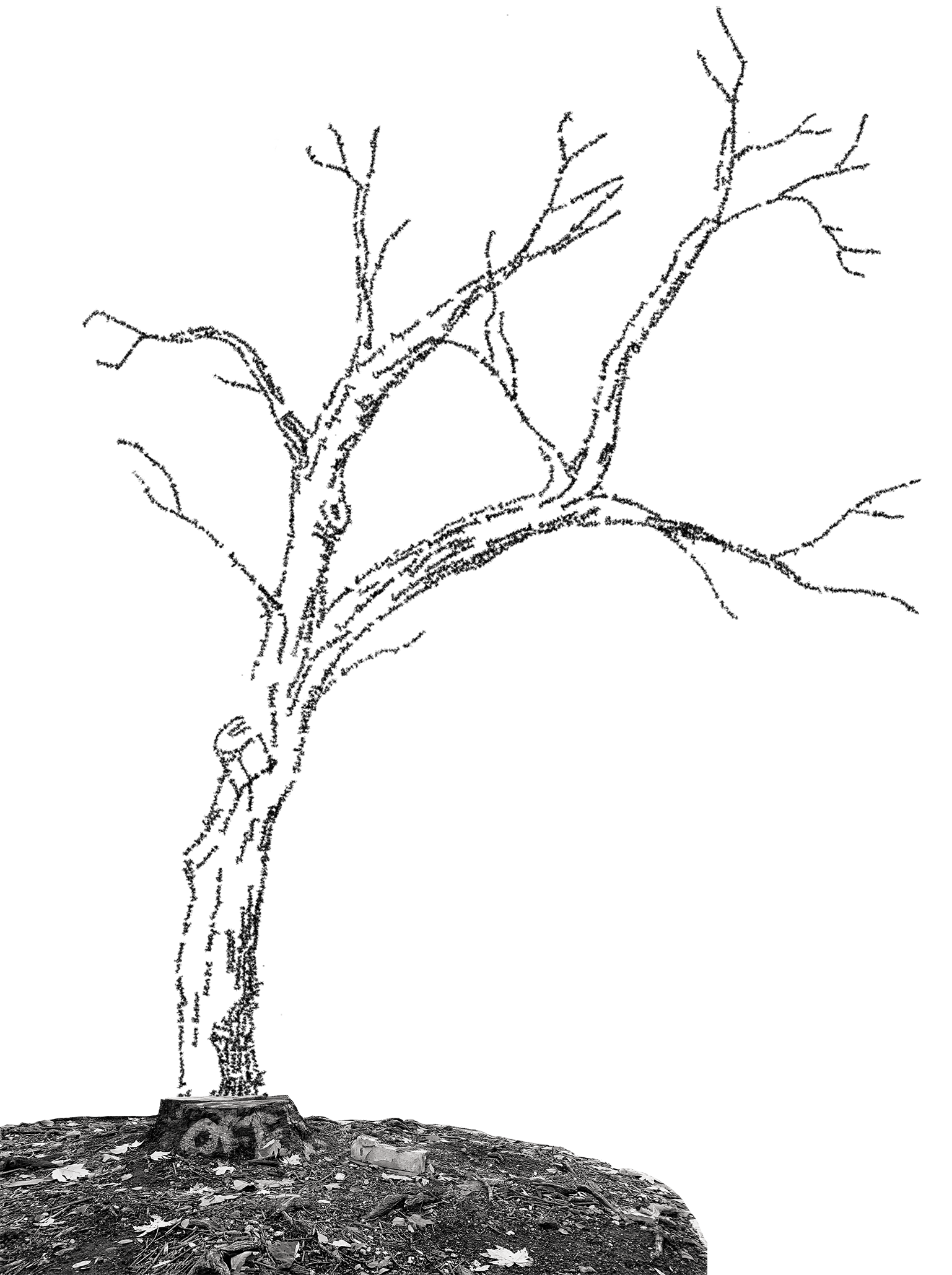

In the beginning of fall quarter, Medill third-year Zachary Watson was biking near University Hall when he noticed something was different: The memorial tree that stood next to the Rock was cut down. Its painted trunk was lying in a pile on the ground next to other debris, discarded like an ordinary tree.

But for many students, the tree was far from ordinary. It was a memorial totheir deceased friends — and its cutting down has provoked broader questions about mental health and spaces of grieving at Northwestern. This tree was a unique way for students to grieve friends that passed on campus, according to McCormick third-year Delan Hao, who is working with other students to create a new memorial.

The roots of the memorial tree go back to two of its original painters, Sophia Ruark and Kimani Isaac. They painted the tree and the Rock in 2017 in remembrance of their friend, Mohammed Ramzan. The memorial stayed on the Rock for three days until it was painted over again, but the paint on the tree lasted much longer.

“When [students] saw the [tree], they felt really emotional,” says Ruark, who graduated from Weinberg in 2020. “A lot of people said that they really liked that it was a memorial place where people could leave flowers and just sit and process and think and just remember all the good things.”

Since then, the tree has served as a symbol of remembrance and a space for students to pay their respects to friends who have passed away throughout the years.

“Losing the tree, it [feels] like I lost my friend all over again,” Isaac says. “But then there’s this other side to it, where it’s so much more important to the community [that] it’s moved beyond just this one person that I was trying to honor, and it’s now become a symbol for all the people that we lose from the time we walk through that Arch to the time we get marched back out of it.

Northwestern Student Affairs contacted Watson and told him that Northwestern’s landscaping facilities cut down the tree because it was dying, but no notice was given to the community before it was cut down. University staff told Watson that they were unaware of the incident as well. But students had already noticed.

“The fact that there hasn’t been some lasting place on campus to honor [deceased Northwestern students] has been a mistake on the part of the university,” Isaac says.

Watson, along with Hao and Medill alumna Allie Goulding, reached out to their peers in the Northwestern community through a Google Form on social media to gather ideas for a new memorial that would serve in place of the tree. In the posts’ comments, current and former students voiced their feelings about how the tree served and expressed their frustration that the University failed to notify students.

Some thought it indicated that Northwestern didn’t prioritize mental health: After all, four of the six students whose names were written on the tree had died by suicide (the other two passed away from accidents). According to Ruark, multiple suicides occurring on a campus as small as Northwestern’s took a big toll on the mental health of the students.

“Every student at Northwestern recognizes that access to mental health helps, and resources are really important for preventing feelings of suicide,” Ruark says. “A lot of [people who personally knew the students who died by suicide] talked about how it was hard to know when someone needed help, and it was hard to know where to direct somebody if they did need help. And I think that, as a community, we all kind of felt a little responsible for each other after those suicides happened.”

As a current student, Watson feels that mental health services for Northwestern students are lacking.

I don’t place the blame on [Counseling and Psychological Services] itself; I place a lot of the reasons that CAPS is lacking for the lack of funds that they get,” Watson says. “They need more counselors that understand the lived experience and the backgrounds of students.”

Instead, he sees the work to improve access to mental health resources as being pushed more by the students than the University itself.

“There are certain groups of students that really, really try to destigmatize mental health,” Watson says. “But I don’t think they’re getting much help from the administration, and they’re having to do all the legwork by themselves, which is not fair to put on students.”

Even so, Ruark recognizes the challenges in providing sufficient resources and support to every student on campus.

“Providing mental health resources for an entire college campus to serve the needs of every individual student is a huge undertaking,” Ruark says. “I think that we have made some strides. But there are definitely ways that our counseling services could be more effective in the future.”

While there are currently no finalized plans or location for the permanent memorial, Goulding, Hao and Watson are all in communication with Northwestern administrators to establish a permanent memorial, such as a garden or sculpture.

According to Watson, the new location will not be at the previous spot near the Rock, but instead a “much quieter, less trafficked space that can be a more contemplative and healing environment.” Hao stressed that no matter what the new memorial looks like, there will be one continuity.

“The really big thing that [students and alumni] had wanted to make sure had stayed the same: That whatever it is, make sure that it was something planned by students rather than just by faculty,” Hao says.