When a club’s acceptance rate is lower than Northwestern’s.

For first-year Sherry Xue, Northwestern seemed like the perfect place to pursue new interests. With 82 performance groups, 34 club sports teams and 13 political organizations, Northwestern is overrun with listservs — an apparent extracurricular paradise.

After an overwhelming club fair, Xue was eager to join the sailing team. She planned to learn ultimate frisbee. She wanted to try consulting through LEND (Lending for Evanston and Northwestern Development), a club that provides microfinance services to Evanston businesses. She was excited to sign up for a Dance Marathon committee.

Xue says she expected the process to be similar to that of high school extracurriculars, where she could join any club as a general member without filling out an application. When emails started to flood her inbox, she found herself filling out application after application. Then, doing interview upon interview. After just a few weeks on campus, Xue faced her first two rejections. She hadn’t made the sailing team and the non-profit division of LEND.

Bienen second-year Mia Park was also frustrated to discover Northwestern’s exclusive club culture.

Upon arriving on campus as a first-year, Park says she wanted to get involved in student theatre and a cappella. When auditions began, however, she found herself too intimidated to even audition; both are notorious for their competitive and time-consuming selection processes.

Park says her fear came from the particularly stressful application process for Delta Sigma Pi, a competitive business fraternity. Along with a written application, candidates were required to undergo three rounds of interviews.

“There were so many things I wanted to try,” Park says. “We are going to college to discover ourselves. The fact that clubs are so exclusive here [is] kind of a shame because a lot of people don’t get to try things that they otherwise would be able to.”

According to Park, her second year at Northwestern hasn’t proven any easier. She has already faced multiple extracurricular rejections upon returning to campus.

Weinberg second-year Halle Petrie is Secretary of Extreme Measures a cappella group. She said although her group would love to be more inclusive, its size restrictions limit the number of new members they are able to accept; an a cappella group can only be so big.

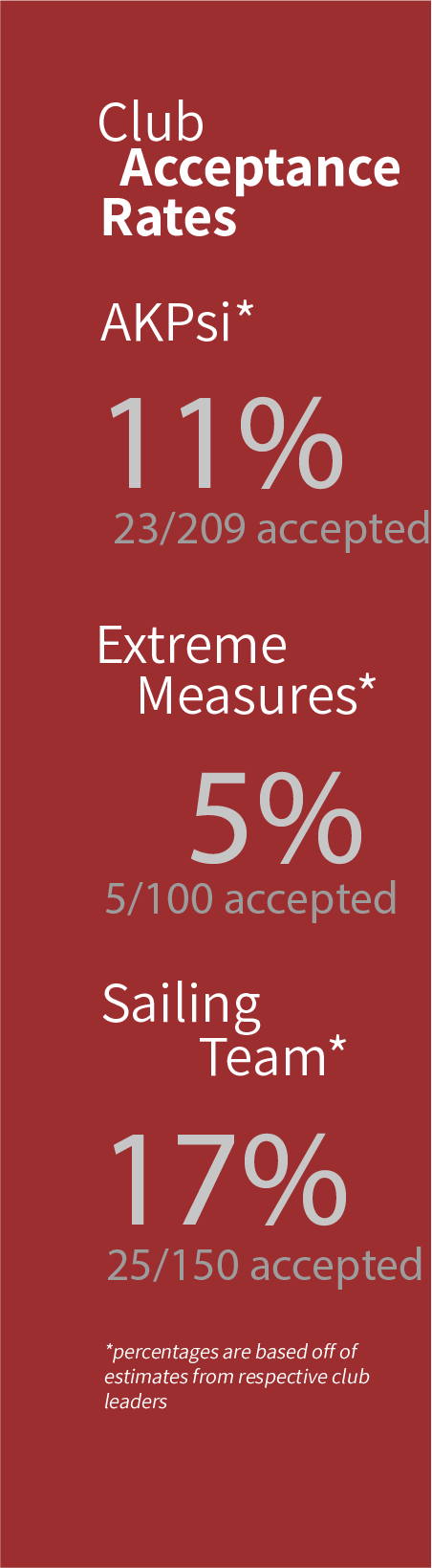

This year, Extreme Measures selected five new singers from the almost 100 who auditioned. This makes its acceptance rate lower than Northwestern’s.

“It’s a very complicated process,” Petrie says. “It’s kind of like a mini-sorority rush.”

After its first round of auditions, members of Extreme Measures choose only 20 to 25 people to call back. They then rank their top choices, engaging in a negotiation process with other groups for the singers they desire, called conferrals. Petrie says much of the decision is based upon a particular voice part or sound a group may need.

“People could be so good at singing and still won’t end up in a group,” Petrie says. “Not because they are not good, just because they weren’t what was needed.”

Although the process can feel frustrating and stressful, she said its competitiveness ultimately makes it feel more rewarding to be accepted.

“When you do get into a group, it feels really special,” Petrie says. “I think the lead-up to it is really cool for people who get into groups. It’s like, ‘I’ve been through all this, and here is my reward.’”

However, SESP second-year Susan Tran believes this feeling itself might be to blame for exclusivity.

“[We] go to an exclusive school with so many type-A, high achievers,” Tran says. “Of course we’re going to [want] to be a part of clubs that make us feel better about ourselves [by] accepting us.”

Last year, Weinberg second-year Alan Chao was accepted into two highly selective organizations: the sailing team and Alpha Kappa Psi, another business fraternity.

Among all of his extracurriculars, Chao says his admission to AKPsi felt most gratifying partly because it was the most competitive.

In fact, he says selectivity was a factor for him in deciding which clubs to try for.

“The selective aspect of [some] clubs made them more appealing,” Chao says. “You want what you can’t have, and being in a club with a lower acceptance rate means something more.”

For this reason, Park wonders if clubs may intentionally display an image of competitiveness.

“I feel like it’s more of the ego of the club [that] makes it exclusive,” Park says. “It’s similar to how colleges decrease the amount of people that they accept.”

Weinberg fourth-year Amos Pomp believes part of the problem is clubs’ criteria for choosing members; he even shared his opinion publicly in a 2018 Daily Northwestern opinion column. He says many make selections based on how well applicants fit socially in the club, rather than their potential to contribute to the club’s mission.

Pomp says an evaluation based upon personality can also make organizations feel more competitive and nerve-wracking to apply for as a first-year.

“As I was applying [to one club], I started hearing that it had historically been a very exclusive club that only friends of people in the club had been a part of,” Pomp says. “It made me nervous because I [thought], ‘I’m not going to get this because I’m not friends with anyone in the club; I’m not like that type of person.’”

In his column, he noted that when recruiting applicants, clubs often choose to highlight how “cool” members are or how much they drink and socialize.

Pomp said certain organizations may even imitate Greek life’s structures, aiming to heighten the social status of those involved.

“I wonder how many talented individuals at NU haven’t applied for certain opportunities because they weren’t interested in the various social activities the organization’s members touted as part of the experience, or because the organization seemed exclusive and off-limits to those without numerous social

connections,” Pomp wrote.

Camp Kesem volunteer co-coordinator and McCormick third-year Zach Shonfeld says the organization requires a competitive application process to make sure all accepted volunteers are committed to the group. However, Shonfeld says its members are currently discussing ways to move toward increased inclusivity. As a service organization, Shonfeld says they would prefer to receive help from as many volunteers as possible.

Some clubs on campus have always remained all-inclusive. Ali Wilt, co-president of Ultimate Frisbee and Communication second-year, says her team will accept anyone at any time.

“The philosophy of the team is not one that cares about being exclusive; we are there to include anyone who wants to do it,” Wilt says. “We have members who join in winter quarter, even in spring quarter. We take them no matter what.”

Compared to other club sports, Wilt says frisbee often finds it hard to maintain consistent goals, with new members constantly coming in and out. Overall, though, she says the choice has proven positive.

According to Wilt, new team members often express appreciation for its lack of competitiveness. Wilt shares in the sentiment that the team environment is more welcoming without an application process.

“I was comfortable more quickly because I knew there was no threat of being rejected,” Wilt says. Repeated rejection has left Park with a diminished sense of

optimism.

“Everything seems so competitive, so I never expect that I will actually get into anything I apply [for],” she says.

However, Park often reminds herself of the practice she is getting for the real world.

“Things are exclusive, and you won’t get everything you try for,” she says.

For Tran, though, the cycle of failure has led to a degree of

numbness.

“I just feel desensitized to rejection at this point.”