“What’s in a name” is a quarter-long project by NBN Opinion in which individual writers explore the personal significance of a name.

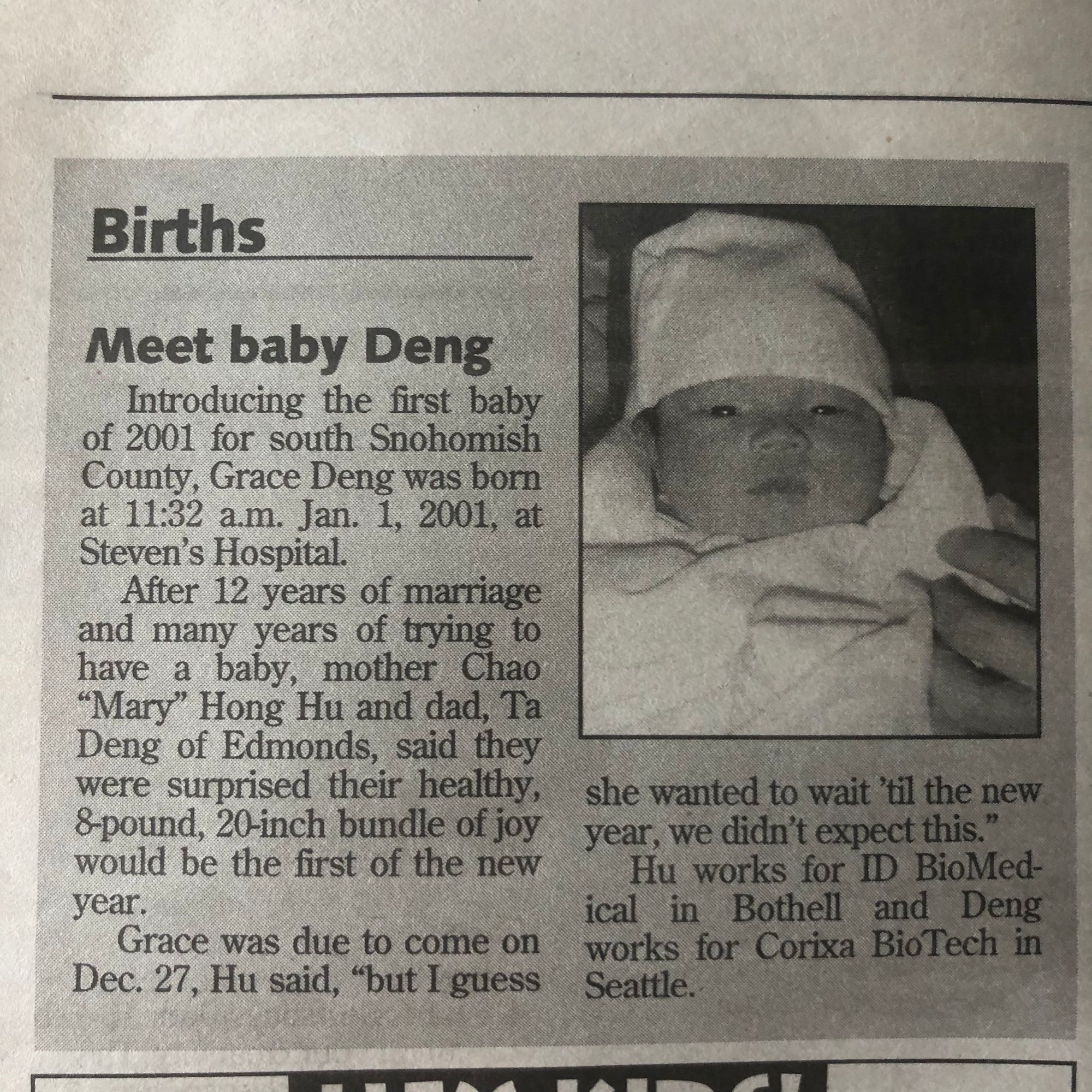

When I was born, my parents knew what they wanted my first name to be – "Grace," because it was the only name they could think of that wouldn’t be made fun of by hypothetical school-yard bullies. They disagreed on my middle name, however – My father wanted to name me “忻语” (or “xinyu,” the official romanization in Chinese), meaning “happy speaking” because he wanted me to be outgoing and lively. My mother wanted my Chinese name to be 忻语 (xinyu) too, but she wanted the middle name on my birth certificate to be Rose – because I was born on January 1, 2001, the same day the University of Washington’s football team won the Rose Bowl.

They compromised. My Chinese name is 忻语 (xinyu), as both of them always intended it to be, but the name on my birth certificate said something else: Shinyu. Squashed between my first name, a good English Christian name, and my last name, a name so quintessentially Chinese, it’s mainland China’s 21st most common surname, Shinyu is neither English or Chinese, but my mother’s best attempt at phonetic translation. “X” in Chinese is pronounced closer to the English “sh,” but not quite – the “x” is a thinner sound, slender and closer to the front of the mouth. My mother wanted Americans — namely, white Americans — to pronounce my name correctly. So she tacked English consonants onto a Chinese name.

The problem with my mother’s reasoning is the “u” in 忻语 (xinyu) is actually ü: a vowel that has no equivalent pronunciation in English. Monolingual English speakers can at least get close to the X in Chinese with a sound that exists in English — but there is nothing in the English language close to what ü sounds like. What’s the point in accommodating English-speaking tongues when they won’t be able to pronounce it right at first glance anyway?

My mother’s decision was well-intentioned: like many immigrant parents, she tried to mold her culture to fit into the new culture she found herself in, tweaking this and that to accommodate the tastes of white America. Growing up, I went past tweaking my culture — I tried to assimilate by cutting my culture out entirely. I was barely out of day care when I came home and declared I wasn’t going to speak Chinese anymore, because no one at school spoke it. I was in elementary school when I insisted my parents pack me a sandwich for lunch, because I was fed up with snarky questions from my peers about the smell of scallion pancakes wafting from my lunch box. I have a vivid memory of hiding my middle name at school, sharing it only with another Asian friend: “I’ll tell you my middle name if you tell me yours.”

I thought that by shedding my Chinese culture as much as I could, I would become more American — more like my classmates around me who never had to question if they belonged. To an extent, my mother did too — "maybe,” I imagine my mother thinking, “just maybe if I change a couple of letters in my child’s name, she will fit in better. She will be more American.”

I’m not the only Asian American who struggles with their sense of belonging. I don’t know a single Asian American who hasn’t suffered under the “forever foreigner” stereotype, a xenophobic assumption that Asian Americans are perceived as foreign, no matter how long it’s been since their family moved to America. Ask any Asian American you know — if they haven’t been asked where they were really from, I’d be surprised. The history of Asians in America dates back to the 16th century — before the United States was even the United States. So why are we still made to feel like we don’t belong?

It’s not the mispronunciation of my Chinese name that makes me feel like I don’t belong. I don’t expect non-Mandarin speakers to pronounce my Chinese name properly — to be honest, I can’t even pronounce it properly myself. But I do expect people to try, to ask about pronunciation, to take a basic step towards integration rather than assimilation. I want to be an American who can carry her Chinese heritage and her Chinese name with pride.

Being Chinese shouldn’t make me any less American, and being American shouldn’t make me any less Chinese. I should be able to be Chinese and American, without sacrificing any part of my culture. I should have been able to learn English and Chinese, to eat scallion pancakes and sandwiches.

And my middle name should’ve been Xinyu.