Bennett Johnson didn’t fully realize what it meant to be rejected because of his race until he moved to 570 Milburn St. in Evanston. He first came to Evanston in the 1930s at the age of two and lived in a tight-knit Black community, but after moving to Milburn Street, he became aware of the segregationist policies the city implemented. His home was only two blocks away from Orrington Elementary School, but he was not allowed to attend because he was Black.

“We had to walk over a mile to Noyes School which was integrated because white kids go to Orrington,” Johnson says.

He says the Black community was restricted to a western part of the city called the 5th Ward, so they had to start their own businesses to serve Black customers.

“It was such a compact community,” Johnson says. “We had a grocery store… We had a hardware store. We had an ice cream parlor. It was a self-contained community.”

Evanston has a long history of segregating its Black residents, many of whom still reside in the city and remember its racist past. This segregation often involved redlining, a process through which Black residents were refused financial services such as housing mortgages to prevent them from moving into certain neighborhoods because of their perceived financial status, often based on stereotypes.

“We were the first Black children that were bussed,” says Rose Cannon, an Evanston resident of almost 73 years. “They used to watch us to make sure the socialization wasn’t too much. That’s really the first time that the segregation got to be painful, and I was painfully aware of it.”

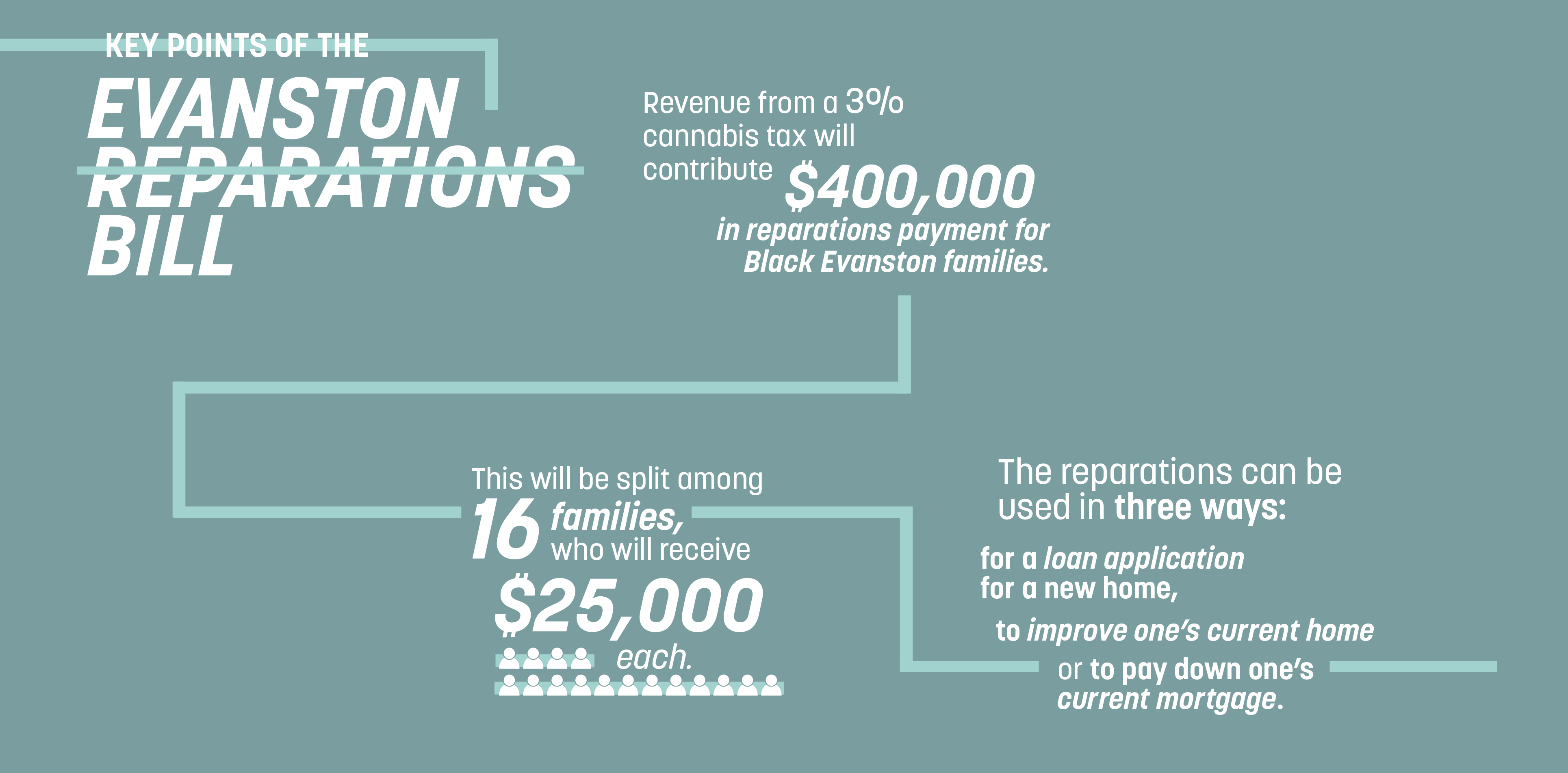

In 2019, the Evanston City Council passed a historic reparations bill, the first of its kind nationwide. This bill was designed to address Evanston’s discriminatory history and repay Black residents for the racist policies they faced. This past March, the City Council voted 8-1 to begin releasing funds for the reparations. But with the bill’s reintroduction into the public eye, concerns about its effectiveness reappeared. Some Black Evanston residents realized that the reparations bill did not include cash payments and that the plan only had enough funds to pay $25,000 each to 16 families — significantly fewer than the number of Black residents harmed by redlining and other discriminatory housing policies.

The bill will take revenue from a 3% tax on recently legalized cannabis sales and redirect it toward assistance for housing loans. The program will dedicate $400,000 from this tax to Black Evanston residents who can prove that they or a direct ancestor lived in the city between 1919 and 1969 and faced housing discrimination.

“I qualify for it. I’m what you call a legacy resident who can trace my roots all the way back here,” Cannon says. “I won’t apply for it because, first of all, it’s not reparations.”

Cannon is not alone in believing that the reparations bill is flawed and not truly reparations. She noted that the bill was not truly reparations because there is no cash payment option. The money goes through a mortgage company and is never in the hands of the actual applicant. As a result, she started looking for a platform to share her criticism and connect with other Black residents who felt the same way.

“When I decided in my heart that I no longer wanted the $25,000 to put as a down payment and I wanted cash, that’s when I started really flipping and looking for people,” Cannon says.

On February 28, Cannon formed the “Evanston Rejects Racist Reparations” Facebook group alongside Sebastian Nalls and Kevin Brown to better educate the community about the inadequacies of the housing program. The page immediately gained attention, boasting over 600 followers by April.

Nalls, a former mayoral candidate and Evanston native, says that it was a surprise to many residents that the reparations program was coming up for a vote, given that many in the Black community had not been informed about the program in the first place.

“We formed with the intention to educate residents about the program, what we felt was wrong with it, what could be expanded on [and] what are the actions that the current City Council could take,” Nalls says.

On the Facebook page, members could talk about the faults they saw in the housing program. Some highlighted the lack of input from Black residents when the City Council created the housing program, the restriction of financial compensation as housing assistance rather than direct cash payment reparations and the program’s minimal impact on Evanston’s wider Black community.

“Residents should be able to choose what they want to do with the money. They shouldn’t be boxed into having to buy a home or any other social equity program,”

Evanston resident and former mayoral candidate Sebastian Nalls

“If they want to take that money and put it into a college tuition fund for their son or daughter, let them go do that," Nalls continues. "If they want to go on a three-month-long vacation in Europe or travel to Africa, let them go do that. It’s not up to the city of Evanston.”

There are only three ways applicants may use the $25,000 from the housing program: pay for a loan application to purchase a new home, use the money towards improving one’s house or pay down the mortgage on one’s current residence. According to Brown, a Northwestern 1981 graduate and Evanston resident for 35 years, this minimizes the benefit of the reparations because applicants cannot receive cash payments and have to process the applications through banks, a white institution that Brown says has a long history of harming Black residents. Banks refusing loans to certain neighborhoods with higher minority resident populations have had long-term adverse effects, including unequal access to healthy food, less access to green spaces and more exposure to pollution.

“This housing program deals with [banks] that have been racist in the past and were the perpetrators of racist policies such as redlining,” Nalls says. “These entities that were responsible for the damage done are now receiving a benefit from the repair that their damage caused.”

This is why the Facebook group name uses the term “racist” to describe the reparations bill. Anyone who qualifies for the program will never physically be able to handle their own money. Instead, it is handled by banks, contractors or a mortgage company — all organizations that have discriminated against Black residents in the past.

According to a 1995 study entitled “Racial Discrimination in Housing Markets: Accounting for Credit Risk,” “the probability of loan denial is 12% higher for Blacks than for whites with equal borrower and loan characteristics and equal predicted credit risk in equivalent equal neighborhoods.” Brown explains that all of the rules of applying for a housing loan also apply to the reparations application, including having a high enough credit score to be considered financially secure.

“I simply don’t believe that you should have to have a good credit score to receive the reparations for a harm that was committed by the industry,” Brown says. Brown says that the amount of $25,000 per applicant, which will only allow for 16 families to receive financial assistance, has been established without any analysis on how many people qualify. He explains how the $25,000 is insufficient to properly address the harm caused by redlining.

Brown provides the theoretical example of a home in Evanston back in 1950 that was worth $50,000. Suppose a Black resident was financially able to purchase that home, but because of redlining practices, was refused the right to purchase it and had to move to a less financially advantageous neighborhood. Then, that same house in the present day might increase in value to be worth $800,000. That Black family missed out on a $750,000 gain in value on a home they could have owned if not for discriminatory housing practices.

“For you to tell me that for the injury I recieved, a $25,000 payment is going to repair me?” Brown says. “That’s what reparations means — repair the harm. How is that repairing?”

Redlining and housing discrimination was a common experience among Black Evanstonians. Cannon has had first hand experience with housing discrimination. In the late 1940s, when Cannon and her husband began looking to buy a home in Evanston, she noticed the real estate agents kept trying to only show homes in the 5th Ward, where the Black community was concentrated.

“At that time, it was awful looking for a house because the real estate agents would make a conscious effort to steer you to the south of Evanston,” Cannon says. “That’s where there were Blacks at the time because the houses are smaller … It’s not the same stuff as you get up in the north end of Evanston.”

Despite the blatant housing discrimination and other forms of racial discrimination Black residents have faced, Evanston still boasts about its diverse background. Under the History and Demographics section on Evanston’s webpage, the city describes itself as “a vibrant community comprising many strong neighborhoods, races, religions and levels of income.”

“Although it calls itself liberal, it hasn’t really been liberal until recently. There has been change because of the Black Lives Matter movement, but there still is racism ingrained in the DNA of our country.”

Evanston resident Bennett Johnson

Nalls attributes the term "performative activism" to Evanston because he notices that the city does a lot to release information or resolutions to condemn racism but very rarely follows through with their statements. While the activism of Evanston’s white residents can have performative attributes, some residents are seeking ways to better understand their white privilege and the issues Black residents have endured.

Although the City Council’s reparations bill is severely flawed, according to the administrators of the “Evanston Rejects Racist Reparations” Facebook Group, Black residents will continue to use their voices to speak out on issues with the housing program and offer suggestions to better help their community.

If he were to create his own policy, Brown says he would start by following South Africa’s example, where they set up a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to help towards repairing the harm of apartheid and directly naming the damage that occured. He would also allocate resources to communicate with the Black community in order to find out what they actually believe is the best form of reparations.

“Black people in Evanston have suffered from racial discrimination, from housing discrimination, from all forms and manners of discrimination that we can think of,” Brown says. “To really help people to understand why this is the right thing to do, you have to educate them about what actually occurred, and that process was skipped.”

Cannon says that there are white allies in Evanston who want to help change the city and have come to her seeking advice on how to better help their Black neighbors. She tells them that they can’t talk over Black voices and they have to listen to their experiences.

“You can’t sit at the table with me and decide what will repair me and what amount of money that I should get,” Cannon says. “And if I’m telling you my story, you can’t talk over me because this is my story, and this is what I’ve lived.”