Weinberg fourth-year Gail Everding practices magic, but she doesn't call herself a witch.

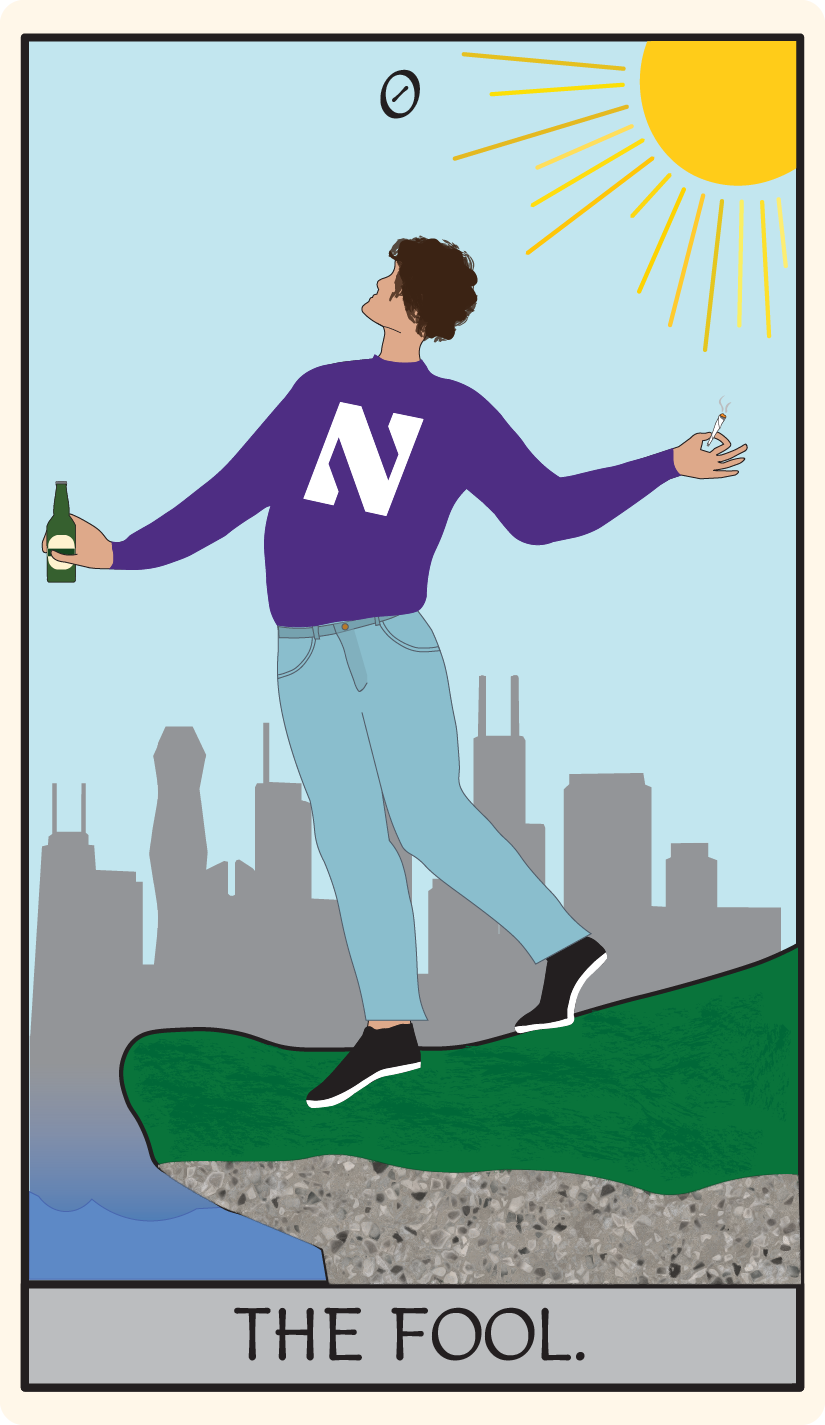

Everding performs tarot card readings, a practice in which cards from a fortune- telling deck are laid out in a specific formation to divine a message about one's life. She also creates sigils, magic symbols representing intentions she wants to manifest in the world. Although most might associate such practices with being a witch, Everding prefers to identify as a magical thinker.

Even among those who believe in and practice magic, defining what it means to be a “witch” is difficult. Everding says that the varying interpretations of “witch” make it hard to use it as a label.

“If I told two different people that I consider myself a witch, they probably have completely different understandings of what that means,” Everding says. “I would rather just explain what I believe, rather than be like, 'I'm a witch,' and they'd be like, 'Oh, so you have a broomstick?’”

The history of witchcraft is vast, with roots in many diverse cultures and traditions. Professor Emeritus of Religious Studies and History Richard Kieckhefer is an expert on the witch trials of the late Middle Ages and has taught a course titled “Religion and Magic” in previous years. This class attracts students like Everding and Weinberg fourth- year Kennedi Holloway who are interested in studying witchcraft and its history.

Through research, Holloway discovered she didn't align with specific magical traditions, but preferred to identify her spirituality in more individual ways, which is how she came to label herself as “spiritual.”

Everding is still exploring various forms of magic. She feels the ability to take this individual approach shows how witchcraft is unlike many religions that focus on one agreed-upon doctrine.

“There's not a lot of room for personal interpretation, usually,” Everding says. “But I found that with witchcraft, it feels like the complete opposite. It's very subversive in the way that the individual subjective experience is what makes it so powerful.”

Weinberg second-year Riley Boksenbaum describes itself as an occultist, someone who identifies with supernatural beliefs more similar to alchemy and astrology than traditional religion. Boksenbaum's subjective experience involves an experimental process. It thinks the idea that magic doesn't align with science is one of the biggest misconceptions about modern witchcraft, as magic “requires a lot of critical thinking and use of scientific methods.”

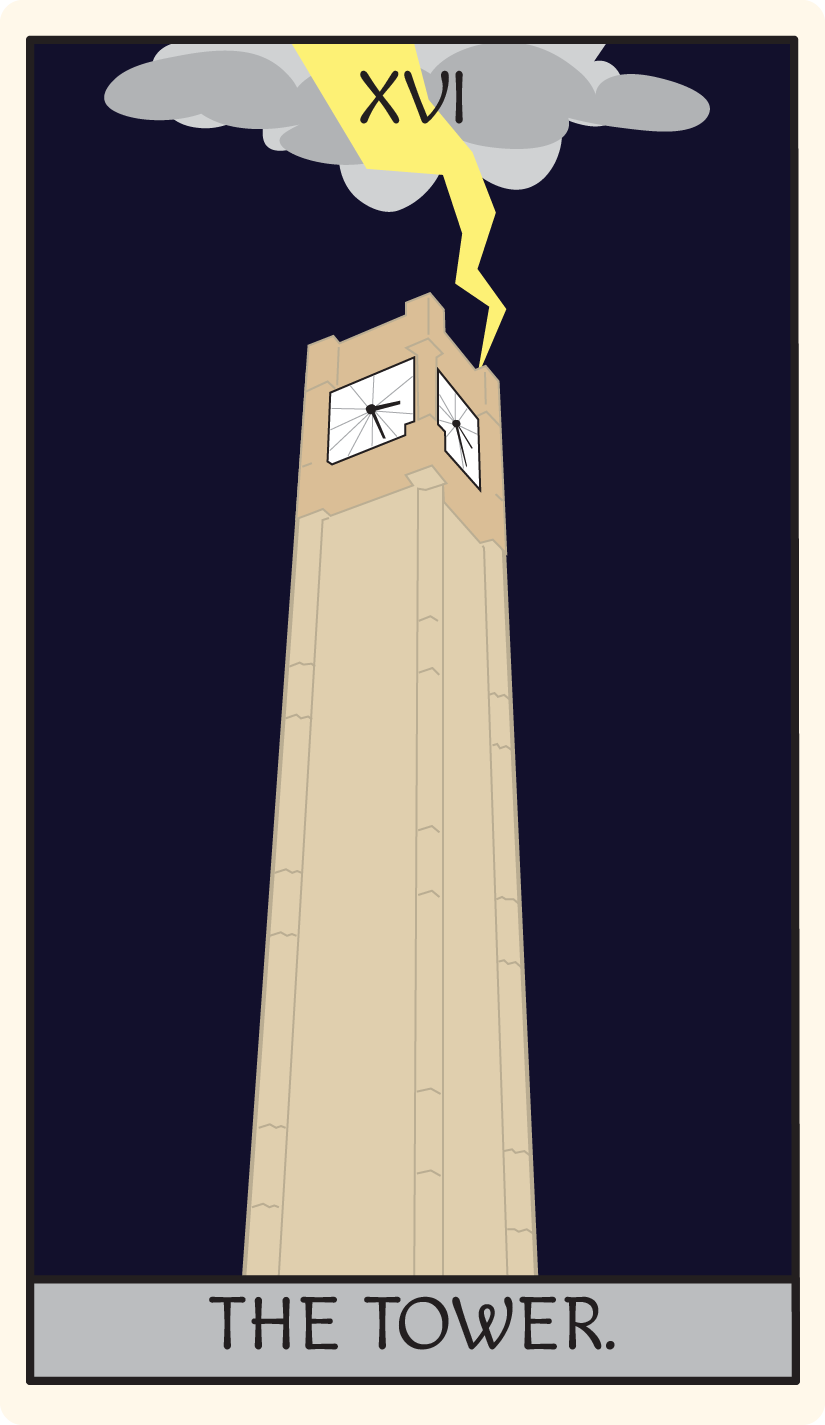

Part of Everding's personal approach to magic is finding places that feel more spiritual to her, like the Koch Memorial Gardens by Deering Library or the Baháí Temple. Holloway also seeks spirituality in nature. Although she feels that Northwestern's campus can be “stale” due to the overwhelmingly man-made landscaping, the proximity of Lake Michigan makes her feel spiritually grounded.

Everding also finds spiritual meaning by interacting with witchcraft online. In April 2021, she watched a tarot reading on Vanessa Somuayina's YouTube channel that told her the next person she would date would be a Taurus born in April who would meet her on a Monday. Everything in that reading turned out true.

When she first started, Everding's Evangelical family was cautious in monitoring her exposure to witchcraft; they called it “demonic.” As a result, her only source of information was the internet — until college. In her search for other magical thinkers, she met Holloway during her first year at Northwestern. While the two practice magic individually, they've both found it has changed their lives for the better.

“The world has no limits for me,” Holloway says. “It's really empowering.”